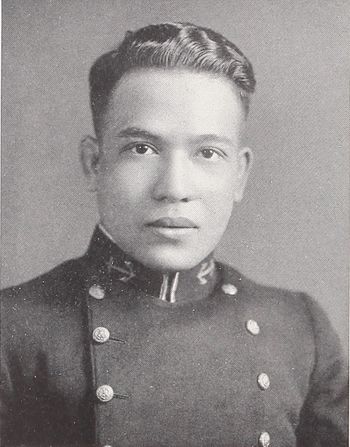

ENRIQUE L. JURADO, LTCOL, PA

Enrique Jurado '34

Lucky Bag

From the 1934 Lucky Bag:

ENRIQUE LOPEZ JURADO

Lucena, Philippines

"Henry" "Hank" "Tito"

BORN with a restless spirit Tito Jurado began very early pondering over geography books. More far-sighted than other boys he decided to join the Navy to see the world. Thus started the Midshipman career of another one of our proteges from the Philippines.

He took very active interest in sports and virtually tried all of them. Trying to discover his talent — so he says. One after another, boxing, soccer and wrestling took his time but he soon gave up the first two. Boxing was too unrefined, soccer too easy to get ones ankles twisted so finally he got settled to wrestling.

Sleeping is his greatest hobby and to see him propped up comfortably in his chair during a lecture is a familiar sight. Having great capacity for making friends and easy going to the last degree, nevertheless, his life at times must have been lonely. To hear him talk of his "tropics" seems as if he missed them and meant to return there. Wherever you may be, may luck and success attend you, Enrique Lopez!

(Happy thought) — Were there any cracks on the pavements of Bethlehem?

Soccer 4. Wrestling 4. 3, 2, 1. "N" Club. 2 P.O.

ENRIQUE LOPEZ JURADO

Lucena, Philippines

"Henry" "Hank" "Tito"

BORN with a restless spirit Tito Jurado began very early pondering over geography books. More far-sighted than other boys he decided to join the Navy to see the world. Thus started the Midshipman career of another one of our proteges from the Philippines.

He took very active interest in sports and virtually tried all of them. Trying to discover his talent — so he says. One after another, boxing, soccer and wrestling took his time but he soon gave up the first two. Boxing was too unrefined, soccer too easy to get ones ankles twisted so finally he got settled to wrestling.

Sleeping is his greatest hobby and to see him propped up comfortably in his chair during a lecture is a familiar sight. Having great capacity for making friends and easy going to the last degree, nevertheless, his life at times must have been lonely. To hear him talk of his "tropics" seems as if he missed them and meant to return there. Wherever you may be, may luck and success attend you, Enrique Lopez!

(Happy thought) — Were there any cracks on the pavements of Bethlehem?

Soccer 4. Wrestling 4. 3, 2, 1. "N" Club. 2 P.O.

Biography & Loss

From Wikipedia:

Captain Enrique L. Jurado (July 15, 1911 - October 14, 1944) was an officer in the Philippine Army - Offshore Patrol during the Second World War. A graduate of the United States Naval Academy, Class of 1934, Foreign Midshipman who returned to the Philippines to teach at the Philippine Military Academy. Later joined its Army Coastal Defense force, the Offshore Patrol (OSP), as an instructor to its' first class of graduates. He was the officer-in-command of the OSP, just before the Pearl Harbor attack on December 4, 1941. He led his squadron of three boats in the Bataan defense campaign, and managed to escape the Japanese when he ordered his flagship to Batangas. After his escape and recovery, he joined the guerrillas in Panay. Jurado was sent to Mindoro to try to consolidate the guerrillas there, but was tragically killed by a rival guerrilla faction.

Philippine Diary Project

The Philippine Diary Project has several entries on Henry's actions during the war.

Remembrance

Originally posted at USNA Alumni Association; there is no date given. It is primarily the life history of his father - Enrique (Henry) Jurado, a Graduate of USNA Class 1934. His life is entwined with the history of the Philippines during WW II

Submitted by Gene Jurado, son of Enrique "Henry" Jurado '34:

PROLOGUE

The Philippine Fleet traces it origin from the pre-war Offshore Patrol – the forerunner of the Philippine Navy. On December 4, 1941 Enrique L. "Henry" Jurado, USNA ’34 became officer-in-command of the OSP, right at the start of the WWII.

Henry Jurado graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy the year the United States agreed to grant Philippine independence in 1934. Henry was a sports lover, a football fan, and he tried his hand at several teams during his Annapolis days. He settled on wrestling after quitting boxing because it was too unrefined and soccer because it was too easy to twist ankles, said his yearbook, The Lucky Bag.

Student records also show that Henry was a freshman participant in soccer but a four-year mainstay in wrestling, earning letterman honors his final three years. He was a tiny, stocky grappler on Coach John Schutz’s squad, weighing no more than 127 pounds but with a chest that expanded to 35 inches.

Sidney D.B. Merrill, a wrestling teammate, said Henry was muscular, quick and a fast learner on the mat.

"I never was able to beat him twice," Merrill recalled. Roy Smith, a Naval Academy student, did not socialize with Henry but knew of his reputation: At the U.S. Naval Academy, it was common to see him propped up comfortably in his chair during a lecture, said his Yearbook, which added he had "… a… great capacity for making friends" and was "… easygoing to the last degree." "Everybody liked Enrique," Smith said simply.

"He was a little reserved, but on the other hand he could be outgoing if he knew you," said classmate James E. Johnson. "He was a good little wrestler. Strong. And he had a good personality."

After graduating from the U.S. Naval Academy, went back home to teach mathematics at the Philippine Military Academy (PMA). Ramon Alcaraz, who entered the PMA in 1936 and later joined the Off-Shore Patrol, remembered Henry as a "very strict and very professional" faculty member.

Henry was a PMA Tactical Officer whose job was to supervise military-drill instruction. He also was "Master of the Sword" or Athletic Director and he coordinated calisthenics, exercise and sports. His specialty was wrestling and he coached the PMA team to a national championship. Later, he went back to the U.S. where he briefly attended flying school at Randolph Air Force Base, then earned an MS in Metallurgic Engineering from MIT.

At that time (1937), he met his wife, Danday Martinez, who had just finished her Masters from Columbia University. Henry then began his Ordnance training at Piccatiny Arsenal in New Jersey and then continued postgraduate studies in Ordnance training at the U.S. Army Proving Ground in Maryland. He returned with his new wife to the Philippines in 1939, just at the time when the Off-Shore Patrol was formally launched as the naval arm of the Philippine Army.

The new Off-Shore Patrol was part of the "Orange Plan". U.S. military experts had speculated, even as early as 1905, — when the Russo-Japanese war ended when the latter surprisingly gained control over Korea and recognized as a world power — that United States supremacy in the Pacific would be challenged someday by Japan.

A contingency plan for a U.S.-Japanese War was thus developed and became know as the Orange Plan. It predicted fighting would occur mainly at sea and made few provisions for protecting the Philippines. The Orange Plan was revised in 1924 to order that the U.S. garrison in the Philippines, roughly 11,000 U.S. troops and 6,000 Filipino auxiliaries, secure the Bataan peninsula in time of war — keeping Manila Bay from enemy hands — until the American fleet could arrive to rescue the Philippines. It was a longshot defense plan at best, based on token forces, minimal spending and wishful thinking.

Leonard Wood, then-U.S. Governor General to the Philippines, predicted in the 1920s that war with Japan could lead to an "abandonment of American posts, American soldiers, an American fleet." But he admitted that to say that to the U.S. public could have a "disintegrating and demoralizing effect."

MacArthur was named Military Adviser to the Philippines on creation of the Commonwealth in 1935. He said the Philippines surely could repel foreign attack and that disbelievers "…knew nothing of war themselves and next to nothing about the actual potentialities of the Filipino people."

According to MacArthur, even with fewer troops and weapons, Philippine forces could fend off enemies through cunning, perseverance and sound defensive strategy. The general and two of his top officers, Majors Dwight D. Eisenhower and James B. Ord, helped develop a Philippine National Defense Act which was quickly passed by the Commonwealth’s legislators. It was signed into law by President Quezon on Dec. 21, 1935.

Joint maneuvers in Manila Bay were conducted in 1941 by the Q-boat squadron of the Philippine Army and a similar group from the U.S. Navy -- PT Squadron 3, commanded by Lt. John Bulkeley (later V. Adm.).

In September, President Quezon signed Executive Order No. 368, calling for recruitment of Off-Shore Patrol officers and men, either by voluntary application or by draft. Q-boat assignments were reserved for men 30 or younger, who had taken an Army physical, completed required training, and had either a Bachelor’s Degree or had passed a Board of Marine Examiners test. The letter "Q" in the name of the torpedo boats stood officially for "quest of mystery" but unofficially for "Quezon." Each vessel was assigned two sets of crew, which alternated after each day of patrol.

The mosquito fleet was small, fast, agile — capable of penetrating minefields, thwarting harbor defenses, and moving undetected among enemy warships to fire their weapons and race away unscathed. These tiny vessels also were known as "Suicide Boats." Officers were taught how to ramrod enemy ships, sacrificing themselves, if necessary to ensure that torpedoes hit paydirt.

Not all military planners, however, were convinced the fleet would be an effective weapon of war. The Off-Shore Patrol had flaws that could be exploited by a large enemy navy because it had too little firepower, too few bases, and no battleships or submarines for backup in fighting. Also, the torpedo boats also had no armor protection, were unable to navigate effectively in heavy seas, and had limited range due to high gasoline consumption by their powerful British-made engines. The mosquito fleet was too small to defend the massive shoreline under even the most optimistic projections — 50 boats — and could easily be outnumbered and overpowered, critics claimed.

But the flotilla was a symbol of something greater than its numbers or firepower — it stood for a changing Philippines, a nation taking steps to defend itself, an era of patriotism, nationalism and hope.

DECEMBER 8, 1941

Rushing home from the Off-Shore Patrol, Henry broke the news to Danday that morning: Pearl Harbor had been bombed. The Japanese had attacked. War had come.

"He was shocked," Danday recalled. "He was thinking about what will happen next, but he was concerned about his family first." Henry told her to pack up and get ready to leave the Manila area — time was of the essence.

"I don’t think this is a safe place to stay, because I’m sure the Japanese will not just attack Pearl Harbor," he said. His words were prophetic. Within hours, bombs would drop on the Philippines.

As the Philippines stood on the precipice of war, Henry found himself commanding the tiny torpedo fleet that was the closest thing his country had to a navy. He tried to prepare Danday for the separation he knew was coming, as the Philippines braced for attack in the hours after Pearl Harbor was decimated by Japanese bombs.

"Because of the movement of the boats, I will not be here," he told Danday. "I’ll be wherever the soldiers are." As troops made their way to Bataan, the Off-Shore Patrol was also ordered to relocate there. The tiny Filipino unit of 3 torpedo boats would operate in seas infested with Japanese aircraft and naval vessels which were attacking enemy craft and blockading ports.

Henry knew very little about the future: whether he would survive, when he could return, what side would win or lose, how the Philippines would weather the crisis. But he knew his country needed him. There was no time for a dramatic sendoff or flowery speeches or tender confessions of love.

"Tears? Of course there were tears," Danday recalled later. "But it was something he had to do. He said something like, ‘You’ll be on your own. Keep your chin up. Be brave.’ What else could he do?"

His message was clear: Duty called.

Philippines President Manuel L. Quezon, vacationing in Baguio, had been informed of the assault on Pearl Harbor in a frantic telephone call from his Executive Secretary, Jorge B. Vargas.

Quezon quickly issued a war manifesto to the Filipino people: "The zero hour has arrived," he said. "I expect every Filipino — man and woman — to do his duty. We have pledged our honor to stand to the last by the United States and we shall not fail her, happen what may."

Nine hours after bombs dropped on Pearl Harbor, Japanese warplanes attacked Clark Air Base northwest of Manila, site of the United States’ largest fleet of overseas planes. It was Monday, December 8th in the Philippines.

The skies were crystal clear over Clark. Dozens of P-40 fighters and B-17 bombers sat idly on the airstrip, and the Japanese invaders met with only token resistance. Clark’s air warning network, based on visual observation and telephone, had broken down and the attack surprised U.S. pilots at the base, many of whom were eating in the mess hall as bombs began falling about mid-day. The result was disaster.

In the aftermath of the assault on Clark and Iba air bases, Japanese pilots met with little resistance as they bombed strategic targets around Manila, the capital of the Philippines. "Have you ever seen a rat trying to find a hole where it can hide? It was something like that," she said of the frantic reaction to Japanese bombing missions. Luzon Island, which encompasses Manila, was the focus of fighting in the Philippines.

The United States quickly pulled its naval fleet, apart from some patrol boats, out of the Philippine waters to avoid total devastation. The warships were sent to the Dutch East Indies. Within days of launching war in the Philippines, Japanese bombers scored a major victory off Malaya by destroying the British battleships REPULSE and PRINCE OF WALES, the two largest Allied vessels in the western Pacific.

The Japanese conducted five small troop landings — with little opposition — on Philippine soil prior to December 22, when it launched a major assault on Luzon by dumping 43,000 troops at Lingayen Gulf.

On Christmas Eve, 2 days later, another 10,000 Japanese soldiers landed at Lamon Bay, creating the last prong of a pincer movement that began closing quickly on Allied troops in the Manila area from the north and south.

Japanese Lt. General Masaharu Homma, who had served with the British army during World War I, planned to capture Luzon within 50 days to meet a Japanese schedule calling for conquest of the entire archipelago in 7 weeks.

MacArthur’s troops outnumbered the invaders but these troops were poorly equipped and many of the Filipino reservists had not yet completed extensive training in basic infantry fire and movement tactics.

Most of the FilAm soldiers fought valiantly. But others fled to the hills at the first sight of enemy troops. The situation quickly reached crisis proportions. MacArthur realized he couldn’t keep the Japanese from landing on the beaches, he couldn’t defeat them from the hills, and he couldn’t stop their march on Manila.

Fifteen days after the outbreak of war, MacArthur abandoned the Filipino defense plan he had helped develop and reverted on Dec. 23 to the old Orange Plan, which he had once vilified. On Christmas Eve, MacArthur moved his headquarters from Manila to Corregidor, an island fortress at the mouth of Manila Bay, to coordinate massive troop withdrawal into the Bataan peninsula. Henry’s Off-Shore Patrol was called upon to assist in the evacuation of President Quezon from Manila to Corregidor, marking the naval unit’s first major accomplishment of the war.

The voyage was short but perilous because Japanese warplanes were a common sight in Philippine skies. Bitter fighting and heavy losses marked the logistically tricky. It had taken a full two-weeks of preparation and effort. Ultimately the withdrawal was successful — but the troops were stunned, battered, weakened. Prospects were bleak.

Two days later, Dec. 26, Gen. MacArthur proclaimed Manila an "open city" — no troops, no resistance — in hopes of saving it from widespread bombing and massive destruction by Japanese troops advancing rapidly toward the capital. "In order that no excuse may be given as a possible mistake, the American High Commissioner, the Commonwealth government and all combatant military installations will be withdrawn from its environs as rapidly as possible," MacArthur announced.

The proclamation was a public concession that seizure of Manila by enemy troops was imminent. For nearly a week afterward — from Christmas to New Year’s Day — the capital city was in limbo: not controlled by the Japanese, not controlled by the United States, not controlled by the Commonwealth.

The mood was tense, apprehensive, uncertain. Some Japanese bombing occurred. Some U.S. troops wreaked havoc by igniting anything that might help the invaders. Some Filipino looting of Army and private warehouses were reported.

For Henry, the time had come to say goodbye. As troops made their way to Bataan, the Off-Shore Patrol was also ordered to relocate there. The tiny Filipino unit of 3 torpedo boats would operate in seas infested with Japanese aircraft and naval vessels which were attacking enemy craft and blockading ports.

Though far from his wife, Henry cherished her memory. When the Off-Shore Patrol recovered a Philippine motor boat half-submerged from a Japanese bombing attack, Henry ordered the vessel refitted within 48 hours for combat duty. He named it the "DANDAY."

If he could not have his wife by his side, at least he would have a constant reminder of her. Henry personally christened the vessel after watching a successful test run following its refitting, which included installation of 30-caliber machine guns at the bow and stern. Henry’s training in ordnance came into play. Thus, Danday’s name became a part of Philippine maritime history.

But she knew nothing about it — then.

Only after the collapse of the Off-Shore Patrol did Danday learn of the 45-foot-vessel that bore her name. "I felt honored. I felt Henry was really close to me and that in his moments of danger, he thought of me," she said later.

WARTIME COMBAT

For Henry "Hank" Jurado USNA ‘34 and his Off-Shore Patrol, the fall of Manila was a call to arms — against overwhelming odds. Their time for combat had come.

Within 100 days, the Off-Shore Patrol would cease to exist and its vessels would never again serve the Philippine armed forces. Grandiose dreams of building a 50-boat fleet vanished with the ravages of war.

But what wouldn’t die, couldn’t die, was the Off-Shore Patrol’s fighting spirit — its courageous stand for freedom amid constant danger and overpowering naval foes. It carved a niche in history.

Decades later, the late President Ferdinand Marcos said, "The legend of the Q-boats was the preview of the story of magnificence that was yet to unfold in the post-war career of the Navy…. It is a story that continues to this day, furnishing us regularly with the spectacle of versatility and steadfastness under fire or under some stressful challenge."

U.S. Commander John Morrill, captain of the QUAIL, an American gunboat, put it more bluntly, "The Philippine Q-boats patrolled further than we did out in the bay and nothing ever got by them. They were fighting terrors and loved nothing better than chasing Jap armored barges."

The legacy of the Off-Shore Patrol is not one of military might but of courage. It was not of superior technology, but of innovation. It was not one of winning the war, but of serving as a beacon of hope to a nation thirsting for freedom.

At a time when Japanese troops dominated the skies and waters of the Philippines, with U.S. troops bunkered in Bataan, the Off-Shore Patrol dared to make the ultimate sacrifice — putting lives on the line, mission after mission. Only 100 days of combat, yes, but each day was historic. This small unit earned the highest percentage in individual awards for heroism and gallantry in action. Sixty-six percent of the officers and men received the silver star from Gen. Douglas MacArthur in January, 1942. When the United States hurriedly pulled its warships from the Philippines after Pearl Harbor’s bombing, only the Off-Shore Patrol and a six-boat PT Squadron under U.S. Lt. John Bulkeley were capable of providing even token resistance to the mighty Japanese fleet. Goliath won, but not without casualties. This became the basis for one of the most popular wartime films starring Robert Montgomery, John Wayne and Donna Reed, and directed by John Ford: "They Were Expendable" (1945) -- A bitter reference to the men who were left behind in the scramble to flee the Philippines after the Japanese conquest. As one of Bulkeley's unit remarked in White's book, after having been presented the DSC by Gen. MacArthur, Bulkeley and his crew learned they were to be left behind while MacArthur fled to Australia:

"Of course to us this meant that the China trip - our last hope of seeing America and escaping death or a Japanese prison - was gone forever. Now the MTB's were like the rest here in the islands - the expendables who fight on without hope to the end. So far as we knew, we would now finish up the war in the southern islands, when the Japs got around to mopping up the last American resistance there." recalled V. Adm. Bulkeley.

Henry’s unit on the OSP, more than 60 in all, were divided into two main groups: sea duty and shore. They were generally in their late teens or 20s, close-knit, representing all walks of Philippine life — from farm families to city dwellers; some with college educations, others not. There were marine officers, naval architects, drydock superintendents, engineers, pilots, clerks, radio telegraph officers. Not one had fought in a world war -- until now.

Gathering together shortly after the announcement that Pearl Harbor had been attacked, the OSP braced for hostilities by preparing machine-gun belts and making sure the patrol boats were mechanically sound and finely tuned. Ten days earlier, the Q-boats had been placed on red alert under war footing, so torpedoes, ordnance, fuel and supplies were packed and ready for action.

As Japanese bombers swept down on Manila and Cavite, December 9 - 10, the Q-boat squadron was determined not to be "sitting ducks" — easy marks — for enemy warheads. The torpedo boats were rushed out to the bay to present difficult moving targets for bombardiers. The strategy worked and not a single Q-boat was lost.

The OSP’s first serious wartime blow, in fact, came not from the Japanese — but from its own men. To keep its 2-story headquarters out of enemy hands, the OSP deliberately burned down the base at Muelle del Codo, Port Area, Manila, as the squadron prepared to flee Manila. The self-induced arson followed a Dec. 23rd Japanese attack on the OSP base that caused no casualties but served as a grim reminder that occupation was near and nothing could stop it.

Henry’s men evacuated 40 OSP personnel from the base December 27th, setting the stage for its destruction. The departure was accomplished amid "…heavy bombing and strafing from three squadrons of enemy airplanes," Henry stated in war records.

The OSP was relocated to Corregidor with whatever torpedoes and vital equipment it could salvage. For several days, Henry stayed behind in Manila and established a temporary headquarters at the Manila Hotel. He and several key officers finally left on New Year’s Day for Corregidor and Lamao, Bataan, aboard the Q-113 Agusan, the OSP’s only Philippine-made torpedo boat. In Lamao, a new headquarters was established at the Lamao Horticulture Center.

For Henry’s men, moving would become routine. The Q-boat squadron would ultimately transfer from Corregidor to Limay to the sandy beaches and makeshift tent-offices of Sisiman Cove, Bataan, while unit headquarters would switch from Lamao to Alasasin Point along the Dinguinin River, Bataan.

OSP personnel not assigned to Q-boats were attached to the 2d Regular Division of Brig. Gen. Guillermo Francisco and given beach-defense duties, manning 50-caliber machine guns along the coast from Lamao to Mariveles until disaster struck.

The beach defenses were overrun by Japanese forces and OSP personnel assisting Francisco’s troops — including Castro — were captured while trying to withdraw along a creek leading to Mariveles.

Henry’s torpedo crews were more fortunate. Not one of the unit’s 3 tiny gunboats — sometimes called devil boats, green dragons or mosquito boats — was sunk during the 3 months of Allied resistance on Bataan, during which time it ferried officials, gathered food and patrolled the coast. But there was much hardship.

Wartime feats of the Off-Shore Patrol included a mission on New Year’s Day, 1942, when Henry’s torpedo squadron was asked to sink every vessel along the Manila waterfront and the Pasig River to prevent their seizure by enemy forces. The mission was extremely dangerous. In one single day, they destroyed about 50,000 tons of shipping without a hitch. Henry was Chief of the Off-Shore Patrol and Navarrete was the Commander of the Q-boat squadron, but they were only small vital local cogs in a much larger war effort. Shortly after the outbreak of war, the OSP was placed under the operational control of MacArthur Headquarters and inducted into the United States Armed Forces Far East (USAFFE).

Rather than map-out war missions, Henry’s job was to make sure his men could carry them out. He coordinated with various OSP divisions, which were effectively split up, and he made sure they received clothing, equipment, military pay and whatever else they were due. While supplies often were sparse among U.S. and Filipino troops, Henry somehow managed to get his crews steel helmets and goggles, which were absolutely vital for high-speed operations at sea. Henry also monitored his men and was aware of their performance, problems and achievements.

When OSP headquarters were in Lamao, Q-boat pilots stopped by every day for instructions from Henry, which prompted criticism from U.S. Col. C.L. Irwin in a Feb. 20 memo to USAFFE headquarters. Irwin claimed the daily ritual appeared unnecessary and forced shoreline defenders to hold their fire, and could "…invite attack of Japanese planes, which will happen sooner or later."

Days later, OSP headquarters were moved to Alasasin Point. For the OSP, the war brought panic, terror, anxiety and uncertainty — but not every day was fraught with fear. There was boredom and drudgery. Long hours with little to do.

Typical of a slow night was this patrol summary submitted by Nuval of the Q-113 AGUSAN to Headquarters: "Area covered: 7 to 8 miles off Lukanin Point and 7 to 8 miles off Balanga shore, a distance of about 15 miles. Time: 10 hours.

"Observations: No bancas, barges, boats or ships were sighted ... No lights were seen around the vicinity. ... No tracers or artillery shells were observed from floating objects. ... Regular radio communication was made with the shore units."

Serving on Q-boats meant crammed quarters, no privacy, no laundry, thunderous engines, churning propellers, gulping food on the run — clutching the boat for safety — and getting hit in the face with shards of whipped water. And amid the separation, uncertainty and shark-infested seas, however, were perks for serving offshore.

Unlike some of their colleagues on Bataan’s beleaguered shore — who ate pancakes three times a day until monkey meat and edible plants could be found — the Q-boat crews had no problem with food. There were plenty of dead fish when Japanese bombs exploded at sea. From ships stranded and abandoned at harbor, the patrolmen were able to salvage numerous blankets, food stocks, military uniforms — even Chinese mah jong sets.

Among the OSP’s most vital tasks was to help carry food and supplies, including ammunition and medicines, from nearby provinces to the battered, isolated troops on Bataan and Corregidor.

The torpedo-boat crews often carried out assignments with total disregard for their own safety, thwarting Japanese warships that blockaded Manila Bay and enemy aircraft that fired upon the speedy Philippine gunboats.

In describing one such mission, Alcaraz wrote of shoving off at sunset from Corregidor with the supply ship KOLAMBUGAN, hugging the shore to escape enemy patrols, dropping anchor about midnight at Looc Cove, Batangas, then camouflaging the ships and contacting officers ashore via prearranged signal.

After sailing triumphantly back to Corregidor one day later, Alcaraz said the shipload of rice and cattle was "… probably equivalent to their weight in gold to the starving USAFFE troops."

Of all the tasks accomplished by the Off-Shore Patrol, perhaps the most heroic came Jan. 17, 1942. This date will always be remembered in the history of the little patrol-boat squadron with pride.

The Off-Shore Patrol’s Q-111 LUZON and Q-112 ABRA were patrolling off the east coast of Bataan when enemy aircraft spotted them and quickly took the offensive. Nine Japanese dive bombers swooped down on the heavily outgunned torpedo boats.

Capt. Navarrete, Henry’s Squadron Commander and skipper of the Q-111 LUZON, OSP’s flagship, later was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Star for his aggressive response to the attack, described extensively in military documents supporting the honor:

Without thought of seeking cover, Navarette maneuvered the boats of his squadron at high speed to positions from which he could attack the hostile planes. When subjected to a dive-bombing attack by the enemy planes, he continued the fire of his machine guns with such accuracy that three hostile aircraft were hit and badly damaged and the enemy was forced to discontinue the attack.

Other Off-Shore Patrol officers involved in the Jan. 17th gunbattle also received medals of valor.

The Silver Star was awarded to Capt. Navarrete’s Executive Officer on the Q-111 LUZON, Lt. Alano, and to the two top officers of the Q-112 ABRA — Lt. Alcaraz, Commanding Officer, and Lt. Gomez, Executive Officer.

No written record exists of Henry’s personal recollections while on Bataan, or his thoughts of the OSP, or any self-evaluation of his performance as head of the Q-boat squadron. But Campo credited Henry’s rigid rules of conduct and no-nonsense leadership with helping mold the wartime Off-Shore Patrol into a distinguished fighting and ferrying unit. Henry was friendly, fearless and respected, according to Campo, but he also was a strict disciplinarian who led "by the book" and did not hesitate to berate his men for minor infractions.

"He was very, very strict with regulations. He refused to accept any violations," Campo reported.

"The performance of the Off-Shore Patrol was exemplary because of the strictness of the chief. I had all the respect for the late Col. Jurado. He was my commanding officer and a good one. ... Nobody would dare not do his duty," Campo later recalled.

One of Henry’s final OSP memos to USAFFE headquarters noted that Sisiman Cove had become a hotspot for enemy attack, dropping bombs about 6 or 7 times a day. "Most of the bombs have fallen so far on the hillsides and on the bay," Campo also recalled. "No material damage has been suffered in the area. The ships in the bay, however, are now dispersing during daytime to avoid congestion."

That same month, Henry was promoted to major. A very small consolation for what was to come. On April 9, 1942, the day Bataan fell, Henry and his fleet of four boats fled to the open sea shortly before dawn. The plan had been hatched the previous day, when Henry gathered his squadron together and proposed to break through the enemy blockade between Batangas and Mindoro to avoid becoming prisoners of war. Henry ordered his men to flee to Panay.

The men of the Off-Shore Patrol liked the idea of leaving with the Q-boats and unit intact. "We wanted to continue the fight. We didn’t want to surrender," Lt. Alcaraz recalled.

Even before the tiny fleet of patrol boats left Bataan, however, its plan began to go awry. Requesting fuel on the day before departure, the Off-Shore Patrol was turned down by an American Depot Officer, who claimed his instructions were to secure all gasoline and lubricants. This hoarding turned out to be a monumental waste. As Henry departed from his base at Sisiman Cove, he saw the sky turn a flaming red on the southern end of the peninsula and knew the military depot — and its stockpiled gas — had been bombed and was burning out of control.

Henry sped away from Bataan in the OSP’s flagship, the Q-111 LUZON. Perhaps mistaken for enemy craft, the Off-Shore Patrol was fired upon by Allied troops on Corregidor but the 65-foot-long patrol boat managed to elude the hailstorm of shells by zig-zagging. Henry, puzzled by the fire from Corregidor, turned to Lt. Campo and asked, "What’s that?"

"Maybe Corregidor wants the OSP to return," Campo replied.

"To hell with them, full speed ahead" was Henry’s answer.

At the mouth of Manila Bay, the squadron slowed to cruising speed, assuming the danger was over. It was not. Somebody almost immediately spotted Japanese zero fighters approaching. Within minutes 7 planes circled ominously overhead. Machine gunners on the Q-boats opened fire and one of the aircraft was shot down, prompting the others to cease strafing but continue circling the LUZON. The zero fighters finally left after a second plane was hit.

As the OSP continued its perilous journey, it came under attack from a Japanese cruiser, 3 destroyers and 6 motor launches near the boundary of Cavite and Batangas. The patrol boats increased speed and zig-zagged, with gunfire erupting around them. The OSP would not survive intact. Racing desperately, the Q-112 ABRA’s engine died and was scuttled by Lt. Ramon Alcaraz in Hagonoy, Bulacan. The crewmen, captured swimming ashore, were imprisoned temporarily. Many later joined the guerrillas.

The squadron’s converted motor launch, the BALER, was overtaken by the Japanese warships and its crew of more than 30 men under Capt. Carlos Albert and Lt. Felix Apolinario were made prisoners of war.

The only Philippine-made vessel in the patrol unit, the Q-113 AGUSAN, managed to veer away and land in Corregidor, where its crew joined Allied forces there until Corregidor was seized May 6.

Henry’s flagship was crippled in the heavy naval attack and had no chance of reaching Panay. Struck by a Japanese shell, the control room of the Q-111 LUZON caught fire which was controlled before it could reach the gas tank, leaving only a trail of thick black smoke.

When the LUZON began taking in water, Henry ordered the limping vessel ashore but it hit a shoal a mile from Nasugbu, Batangas and destroyed.

Japanese warplanes continued their attack on the helpless Q-boat, forcing Henry to order his men overboard. So the Japanese helped to keep the LUZON from falling into their hands, Henry ordered his men to jump overboard. "The last order of Jurado was, ‘Every man for himself. Destroy everything," Campo recalled.

"I tore my secret maps. We threw everything classified into the water. And then we swam."

While in the water, Campo said he was stunned temporarily by an enemy shell — perhaps a rocket. "When I came to, I continued swimming. Meanwhile 6 Japanese planes continued to strafe us in the water and went round and round. We just prayed that no bullet would hit us," Campo continued.

The men were "crawling like crabs" to the Nasugbu beach, Campo recalled.

Even on shore, the Q-boat crewmen were in danger. Japanese shelling continued from warplanes and ship.

"I was shouting, ‘All hands freeze. All hands freeze. Everybody keep quiet. Don’t move, don’t move’ — to make the Japanese believe we were all killed," Campo said.

He heard of one colleague nicked in the right thumb but nobody was seriously injured by gunfire, Campo said. To avoid detection, the crewmen separated. In the confusion, Campo lost track of Henry, who hid underwater at a fish pond along the coast until darkness fell and he could slip away from the heavily guarded area.

Japanese officials informed residents of Nasugbu that they were looking for crewmen of the wrecked boat, and some members of the stranded OSP unit were captured by a patrol unit. But Henry was not one of them. Weak with malaria, he spent about a week hiding in a local barrio, Wawa, while planning an escape to the home of Danday’s half brother, Dr. Felino Salazar, who owned a farm about 25 kilometers away.

The driver of a horse-drawn rig agreed to risk reprisals by the Japanese and provide the transportation Henry needed, but there was a catch. He wanted payment. Henry had no money. The two finally agreed on a deal in which Henry got what he needed most by giving away something he valued most: His wedding ring.

The OSP only lasted 100 days and Henry Jurado joined the USAFFE/Guerrillaforces from Panay which numbered around 8,000 and which had direct contact with MacArthur in Australia. In late 1943 or early in 1944, Henry was sent to Mindoro to establish observation posts covering Verde Island Passage and to establish a base for intelligence penetration into southern Luzon.

The rest of Henry's life (he died on Oct. 19, 1944 -- one day before MacArthur returned to the Philippines) was spent with the Panay guerilla forces, trying to consolidate the remnants of the diverse guerilla elements, each laying claim to be the undisputed power on each island. The natives were frightened of the Japanese and also distrustful of factions of the guerilla forces who were armed and unruly and who, at times, expropriated (in the name of the country) whatever food and livestock which was available. In the nearly three years when Henry fled to the mountainside and organized his band of fighters, he maintained contact with American forces in Australia and there was a semblance of an actual guerilla/USAFFE organization operational in many places. Henry's territory was near the area where MacArthur waded gloriously ashore with no opposition -- perhaps a tribute to the good intelligence reports which Henry and his group provided.

Along the way, Henry was weakened by malaria and attacked by spears by his countrymen. His wife and small boys were jailed by countrymen who wanted to give them up to the Japanese as a peace offering. In the end, Henry was doomed by his unwillingness to surrender to Japanese troops and was ultimately killed by a competing band of Filipino guerrillas. Henry’s legacy has been ensured in ways ranging from the naming of a Philippine Navy patrol gunboat after him to the designation of the Philippine Military Academy’s gymnasium as "Jurado Hall." Another gymnasium at Camp Bonifacio is named after him. His name is written on the shrine at USNA’s Bancroft Memorial Hall appropriately, with the large motto: "Don’t Give Up the Ship" etched in golden mosaic tiles above the altar; and on a bronze plaque on a staircase at USNA’s Dahlgren Hall, as well as a bronze plaque at Rizal Memorial Coliseum, a major sports arena in Manila.

Shipmate

From the Class of 1934 column in the May 1974 issue of Shipmate:

Here is the follow-up on the Hank Jurado case, from none other than Hank Miller: "I was CO of Sangley Point, from Aug. 1955 to Aug. 1957. I inquired about Hank Jurado as soon as I got there. Commodore Joe Francisco (USNA 1930) was then CNO of the Philippine Navy followed shortly by Captain Navarette. They both told me that Hank had been killed during WWII. When the complimentary copy of By the Mark 20 was sent to me to deliver to his widow, Lucy and I did just that. We went to Quezon City and presented the Mark 20 to his lovely widow. She is a very charming lady. We also met his son. It was a most pleasant visit. Hank's brother was in the Philippine Air Force and I am almost certain he got to be a Brigadier General. I saw him several times. So, this is the story on Hank Jurado from my spot in the Philippines. Other Filipinos who knew him check out Joe Francisco's and Capt. Navarette's story. And, of course, Lucy and I met his lovely widow and son. She was teaching school."

Honors & Namesake

The Philippine Navy commissioned BRP Enrique Jurado (PG-371) in honor of Henry. Wikipedia lists several other other memorials, including a plaque in Dahlgren Hall at the Naval Academy.

Book

THE ULTIMATE SACRIFICE: MEMORIES OF ENRIQUE L. JURADO: WWII OFFICER, GUERILLA, PATRIOT by Jim Sanders.

Memorial Hall Error

Wikipedia lists his rank and service as Captain, USAFFE. He appeared in the March 1952 (not a typo) issue of Shipmate: "ENRIQUE JURADO, '34, (Lt. Col. Philippine Army). Died about 15 December 1944, prior to the invasion of Mindoro." Memorial Hall has him as a LTCOL, USA.

The "category" links below lead to lists of related Honorees; use them to explore further the service and sacrifice of alumni in Memorial Hall.