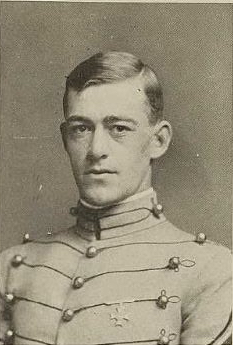

HARRY A. FLINT, COL, USA

Harry A Flint '11

Lucky Bag

Harry A. Flint is listed on the page of "Bilgers." He was appointed to the Naval Academy on May 10, 1907. Unable to determine when he resigned, though it appears he completed his Plebe year.

The Howitzer (West Point Yearbook)

From the 1912 Howitzer:

Harry Albert Flint

St. Jonsbury, Vermont

"Paddy"

FOUR years ago Paddy came in with the intention of winning his way into the Cavalry and, strange to say, still can't see anything but that yellow stripe. He is our Uncle Eddie's side partner in the polo line and does mighty well at it, as he does at most things he makes a try at. Paddy is not reticent about his troubles but he has a very queer way of telling them; he just keeps quiet, and his looks are those of old man Grump himself. For most of us reveille is L.P., but for Paddy it is a fearful thing and, until the benign influence of that after-breakfast skag has taken effect, the gloom about him is thick. We have seen the clouds break and the sun shine through the rift, especially on leave; so we know there is a lining after all.

Corporal, First Sergeant, Captain, Sharpshooter, "A" in Football, Football Squad (4, 3, 2), Lacrosse (4, 3), Hundredth Night Business Manager (2), Howitzer Board, Horse Show, Toast New Year's Dinner 1912.

Appointed from Senatorial Vermont

Harry Albert Flint

St. Jonsbury, Vermont

"Paddy"

FOUR years ago Paddy came in with the intention of winning his way into the Cavalry and, strange to say, still can't see anything but that yellow stripe. He is our Uncle Eddie's side partner in the polo line and does mighty well at it, as he does at most things he makes a try at. Paddy is not reticent about his troubles but he has a very queer way of telling them; he just keeps quiet, and his looks are those of old man Grump himself. For most of us reveille is L.P., but for Paddy it is a fearful thing and, until the benign influence of that after-breakfast skag has taken effect, the gloom about him is thick. We have seen the clouds break and the sun shine through the rift, especially on leave; so we know there is a lining after all.

Corporal, First Sergeant, Captain, Sharpshooter, "A" in Football, Football Squad (4, 3, 2), Lacrosse (4, 3), Hundredth Night Business Manager (2), Howitzer Board, Horse Show, Toast New Year's Dinner 1912.

Appointed from Senatorial Vermont

Loss

"Paddy" was lost on July 24, 1944, while leading a patrol in the hedgerows of Normandy. He was the commanding officer of the 39th Infantry Regiment, 9th Infantry Division, and had been so through the Sicily campaign of 1943.

Via Arlington National Cemetery; published August 21, 1944:

There was no doubt about it—at 56, cavalry-trained Colonel Harry A. Flint was overage to command infantry in battle. Yet there he was, in France, a happy dust-caked fugitive from half a dozen cushy supply and liaison jobs that were always threatening to keep him out of combat.

In France, as in North Africa and Sicily, "Paddy" Flint's aging, horse-bowed legs sometimes let him down in battle. When they did he would sit down for a spell. His men knew, and they loved him for his nerve. It was soldier's talk that "Ike" Eisenhower, a West Point plebe when the Colonel was a first-classman, had something to do with keeping Paddy up front. The arrangement suited old Paddy right down to the ground. France, beamed the ruddy Colonel, was his "graduation exercise" as a footslogger.

On the Saint-Lô-Périers road, Paddy's outfit was held up by heavy mortar fire. Up front, as usual, the Colonel and a rifle patrol soon found the trouble. Said Paddy over the walkie-talkie: "Have spotted pillbox. Will start them cooking."

He called for a tank, rode atop it in a rain of fire as it sprayed the hedgerows. The tank driver was wounded. Paddy crawled down, went forward afoot. A sniper's bullet got him as he led his patrol into the shelter of a farmhouse.

Aid men soon came up, loaded the Colonel on a stretcher. Said a Private as they started to the rear: "Remember, Paddy, you can't kill an Irishman—you can only make him mad." Colonel Flint smiled. Next day he died.

Paddy was survived by his wife, Sallie. He has a memory marker in Vermont; he is buried in Arlington National Cemetery. His first burial service, in France, was attended by General Patton.

Biography

From Notorious Ninth:

Harry Albert Flint was born on 12 February 1888 in St. Johnsbury, Vermont. His parents, Mabel and Charles G. Flint, lived in a small house in St. Johnbury with their seven children. Harry was the third in line. This young boy’s interest for the military thing came up very early, perhaps inspired by the Philippines War stories that came back in Vermont at the end of the nineteenth century. He was a 11 years young boy, and he already dreamed of a glorious military career.

In 1903, the young Harry finished his studies at the elementary school and entered high school. All through his youth, Harry never missed the opportunity to be an active young boy. He was an outdoor man, and excelled as a horseman. At the end of his high school period, a friend of him suggested the next step in Harry’s life: why wouldn’t he join the famous military academy of West Point? For Flint, that did make sense. He already knew he wanted to become a cavalry officer. On 2 March 1908, Harry’s dream came true, when he was admitted in the United States Military Academy as Fifth Class Year Cadet, at the age of 20.

During his years as a cadet, he worked hard to become a cavalry officer, and met a fellow cadet named George S. Patton Jr., who soon became a close friend of him, and they created together, a friendship of a lifetime. If Paddy never excelled as a cadet, he never failed neither. Except in playing polo, first common denominator with George S. Patton Jr. But polo wasn’t his only activity: he was fascinated by sports, thank to which he emerged to be a real leader. In 1912, he logically graduated West Point Academy and as commissioned second lieutenant in the 4th Cavalry Regiment. Three years later, two others later known cadets graduated: Dwight Eisenhower and Omar Bradley, which Paddy met when he led their instruction company.

During the Punitive Expedition 1916-1917, Flint’s desire for action was frustrated by his assignment at Fort Riley, Kansas, rather than in Mexico with his unit. When it appeared that the United States were going to get into the Great War, Paddy was transferred to the artillery, as a mean to go into combat. Though he served in France, his regiment was a replacement unit rather than a fighting outfit. After the Armistice, he joined the Third Army in Koblenze, Germany, performing in various capacities, including “remount Officer”, for which he received the Cross of Czechoslovakia “because they felt I had been honest with them in horse trades.” He also won a citation from his own government for jumping into a switch-engine cab and driving a trainload of high explosive through the flames of a burning ammunition dump out to safety.

Returning home in 1921, Major Flint started a succession of assignments: Cavalry School, General Service School, Command and General Staff School, New Mexico Military Institute, Ecole Supérieure de Guerre in Paris, France (where he became fluent in French), Office of the chief of Cavalry and even Air Corps Tactical School. In 1933, he joined the 1st Cavalry Regiment (Ft. Knox, Kentucky). In 1935 he became Lieutenant-Colonel and headed the Cavalry ROTC at the University of Illinois. From 1939 to 1941 he was in the 5th Cavalry Regiment, in the process of becoming a full-bird Colonel. In 1941, Paddy joined his friend George Patton in the 2nd Armored Division at Ft. Benning, Georgia.

When the war started, Paddy was desperately seeking for a combat assignment, but was over the age limit. But Paddy couldn’t imagine that war coming up without serving in a combat unit: for too long, he has been aside the battlefields. Hopefully, he could rely on his different contacts he made throughout the years, and especially on his good old friend, Major General George S. Patton. Finally, Flint received on June 29, 1942, the following order:

1. The Secretary or War relieves the following named officer from assignment and duty as indicated and assigns him to permanent station outside the continental limits of the United States, temperate climate, Headquarters, SOS, European Theater, London, England. He will proceed to Indiantown Gap Military Reservation, Indiantown Gap, Pennsylvania, reporting not later than July 10th, 1942 to the Commanding Officer, Special Troops, SOS, for transportation to destination. Upon arrival to London, England, he will report to the Commanding General, SOS, European Theater, for duty with the BI Detachment. Colonel Harry A. Flint, O-3377, Cav., 2nd Armored Div., Ft. Benning, Ca.

2. Prior to his departure from his present station, he will be equipped for extended field service, including steel helmet and gas mask, and will have in his possession WD, MD, Form 81, showing inoculations and immunizations required before leaving the continental limits of the United States, and will require physical inspection as prescribed by par. 14, AR 40-100, as amended by Sec. III, Cir. 31, WD 1942.

3. Individuals should advise their correspondents that mail will be addressed to them at “Hq., SOS, APO 1094, c/o Postmaster, New York, N.Y.”

But after a certain time in London, Paddy soon realized that he was still far from his dreamt combat command, working through paperwork and administrative burden. But Paddy worked every day to “fight the fight”. And on November 8th, 1942, he was part of the North Africa invasion. Not as a combat soldier, but still part of the invasion.

Paddy was assigned to the G-3 Desk in Oran, working for the supply chain which was a challenging post, but by the end of December, rules and doctrines were changed, threatening the 54 years officer’s job longevity. At that time of the North African campaign, the Allied wanted more cooperation with the French authorities. And on this late December 1942, Paddy was sent to the French Headquarters in Algiers, as a Liaison officer. Actually, the French authority was held by General Giraud, who was, back in the days, Flint’s instructor at the French École Supérieure de Guerre in Paris. So, who better than Flint to liaise with Giraud?

In early January, Flint received a letter from the Commanding General of the I Armored Corps:

My dear Paddy,

I hope you like the job with Giraud, as I was the one who recommended you for it, remembering well your stories of him when we were together at Benning. Jake Devers was here yesterday and told me you were doing a grand job.

If you are looking for fighting, it is my advice to keep away from me as I do not seem destined to get in any for the time being, but if things brighten up, we shall certainly get together.

Devotedly yours,

S. PATTON, JRPaddy was actually doing so great with Giraud that they became good friends. His job anyway, was of the utmost importance since he had to understand precisely everything going on between French, Americans and British on the North African Theater. Eventually, Giraud presented Flint the French well-known distinction “Légion d’Honneur” – Legion of Honor – with the rank of Croix de chevalier (Cross of the Knight). Meanwhile, Rommel was inflicting a major setback to the U.S. forces at Kasserine Pass. The unlucky General Fredendall had to be replaced, and Ike chose Patton to restore the backbone and the fighting spirit of the II Corps. And at that very same time, coincidently, Flint was relieved from his liaison post to be assigned to… the II Corps Headquarters in Southern Tunisia; and when the very noisy motorized column drove Patton to his new headquarters, no doubt Paddy was rolling along.

Invasion of Sicily was on planning, with Patton and Montgomery in charge. Patton received a new command, the 7th Army, leaving the II Corps to General Bradley. Flint, having worked as Staff Officer, certainly knew the new plan on going, so he simply paid a visit to General Bradley, to ask for a combat unit assignment… as simple as that. So before the end of April 1943, Paddy knocked at Bradley’s doorway and asked an old friend a favor.

“Brad, I’m wasting my talents back in the rear shuffling papers (…)” he told the General. It is hard to know what the response of Bradley was, but Paddy had nothing to lose, being a 54 years officer with 31 years of Army behind him. Paddy had to go back to Algiers, where few days later, he received a new order that assigned him, again, to the 2nd Armored Division, just before the Operation Husky, invasion of Sicily. A new chance – and hope – to join a combat unit for the optimistic Paddy.

He then was assigned as Detachment Commander (Det. Co.) of the 2nd Armored Division’s Headquarters, while at the same time, General Bradley and Major General Manton S. Eddy – 9th Infantry Division Commander – were having a conversation back at the II Corps headquarters. Soon after the defeat of the enemy in Tunisia, Eddy went to see Bradley with the 39th Infantry Regiment in mind: “the 39th’s confidence and fighting spirit need a boost”. Moreover, that unit was planned to take part to the Operation Husky, and Eddy wanted a new regimental commander. Bradley agreed, remembering an earlier conversation. And he promised General Eddy to send him… a fifty-five years old cavalry officer!

The 39th Infantry Regiment landed on July 14th, 1943, at Licata. It was then commanded by Colonel William Ritter, third regimental commander since the unit landed in North Africa, nine months earlier (Colonels Benjamin F. Caffey and J. Trimble Brown preceding). The regiment was ready to fight, and was attached to the 82nd Airborne Division for the beginning of the operations in Sicily. Colonel Ritter could rely on good and experienced battalion commanders, such as Van H. Bond, 3rd Battalion commander. But one day as the regiment was pushing to Castelvetrano, an enemy aircraft overflew the HQ vehicles. Ritter stepped out of his command car (against the directives spread out to not off-load their vehicle in case of aerial attack) and another officer in the car jumped off as well, hitting Ritter and breaking his leg. The regimental commander was then evacuated, and Lt. Col. John J. Toffey, X.O., took over the regiment (he will be killed later on during that campaign).

Under Toffey’s command, the 39th Infantrymen were progressing, from success to success, But at the rear, the conversation between Eddy and Bradley was certainly not forgotten, and if Toffey was Acting Regimental Commander, Manton still wanted a new boos for his 39th Infantry Regiment. And on July 25th, 1943, Flint, still working on his paperwork, received a new order: TO: COMMANDING OFFICER, 7TH ARMY REAR. SEND COLONEL H. A. FLINT, 2ND ARMD DIV BY FIRST AVAILABLE AIR X PATTON TO HARVEY

The biography, undated, promises part II "soon;" as of June 6, 2018 it was not posted.

Photographs

Career

From Arlington National Cemetery:

A graduate of West Point in 1912, he came to Britain in 1942 in the Services of Supply. He met Lieutenant General George S. Patton, Jr. in London and convinced his old friend to take him to North Africa. A supply officer in North Africa at first, Colonel Flint later commanded the Fifty-sixth Armored Infantry Regiment and then an Infantry Regiment. He fought through the Sicilian Campaign and won the D.S.O. and the Silver Star with Clusters.

Colonel Flint was born in Vermont. In World War I he served in the Cavalry and the Field Artillery.

Remembrances

From a letter written by Major General Manton S. Eddy, commanding general of the 9th Infantry Division, on July 27, 1944:

Yesterday morning a soldier of the 39th Infantry was buried in the American cemetery at St. Mere Eglise.

The grave he now occupies is a simple one–a soldier’s grave, no different from the other graves of your comrades row on row beside it. Only one thing about it will make you and me remember it for the rest of our lives–the dog tag on the cross reading ‘Harry A. Flint.’ That dog tag doesn’t make much of an epitaph, but the soldier lying beneath would be the first to say ‘hit don’t make no difference.’ It does make a difference, however, to every one of you and to me to know that Paddy Flint will lead you no longer. His loss cannot be measured by words, but his death means to your regiment, to this division and to the United States Army the loss of a gifted and lovable leader, and to each of us the passing of a personal friend.

One thing will never be lost–our memory of him as your regimental commander in Sicily, in England, and in Normandy. It is this memory which will carry your new commander and every fighting soldier of you in the same direction in which Paddy was leading you when he died.

Keep that memory with you–depend upon your new leader–carry your fight to the finish. I am going to do the same. Major General Manton S. Eddy

From "A Soldier's Story" By Omar Nelson Bradley:

The morning [General] Allen drove into Troina [Sicily] his 1st Division was accompanied by the 39th Regiment of Manton Eddy's 9th Division. At the head of that unit trooped its bold and eccentric commander, the indomitable Colonel Harry A. Flint of St. Johnsbury, Vermont. Stripped to the waist that he might be more easily identified by his men, Paddy Flint wore a helmet, a black silk scarf, and carried a rifle in his hand. The battle at Troina marked the start of his brilliant but brief combat career.

An old-time cavalry crony of Patton, Flint first appeared at the II Corps CP in Beja to beg a line command that he might get into the shooting war. At the time he was assigned to AFHQ in Algiers. "Hell's bells, Brad," he complained, "I'm wastin' my talents with all those featherbed colonels in the rear—"

Soon after the Tunisian campaign ended Manton Eddy asked for a regimental commander to spark up his 39th Regiment which then showed signs of sluggishness in contrast to its spirited companions.

"What we need in the 39th is a character," Eddy said.

I sent him Paddy Flint.

After landing in Sicily Manton reported to corps at Nicosia with Paddy Flint in tow. The 39th was to he attached to Terry Allen for the Troina attack. The remainder of Eddy's 9th Division had not yet come ashore.

"Brad," Eddy whispered when Paddy ambled off to the G-3 tent for a briefing, "have you seen this?"

He held Flint's helmet in his hand. On its side there was boldly stenciled "AAA-O."

"And just what in hell does that mean?"

"Anything, anytime, anywhere, bar nothing—that's what it means. Paddy has had this thing stenciled on every damned helmet and every damned truck in the whole damned regiment."

I grinned.

"But haven't you issued some kind of a corps order about special unit markings?"

"Manton," I answered, "I can't see a thing today— Nope, not even that helmet of Paddy Flint's?'

To help his regiment gain confidence under enemy fire, Paddy would stroll about the front, unconcernedly rolling a cigarette with one hand. With his rifle in the other he would gesture scornfully toward the enemy lines.

"Lookit them lousy Krauts. Couldn't shoot in the last war. Can't shoot in this one. Can't even hit an old buck like me."

These antics of Flint's worried me.

"Someday, Paddy," I once chided him, "you're going to walk around like that and get killed. Then you're going to prove just the opposite of what you're trying to teach your men."

He looked at me strangely for a moment. "Hell's bells, Brad," he said, "you know them Krauts can't shoot—"

Paddy was killed in Normandy when a German sniper shot him in the head. I'm certain he would have called it a lucky shot but even this satisfaction was to be denied him. For though he lived several hours, the wound had impaired his power of speech. Paddy died, a silent Irishman with a grin on his face.

Distinguished Service Cross

From Hall of Valor:

The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress July 9, 1918, takes pleasure in presenting the Distinguished Service Cross to Colonel (Cavalry) Harry Albert Flint (ASN: 0-3377), United States Army, for extraordinary heroism in connection with military operations against an armed enemy while serving as Commanding Officer, 39th Infantry Regiment, 9th Infantry Division, in action against enemy forces in August 1943 near Troina, Sicily. Going forward with the attacking battalions, Colonel Flint spent his entire days moving about the squad and platoon installations to cheer and encourage all ranks. During the attack on 4 August 1943 he personally led the advance through enemy fire, waving to his men to follow him forward. He was often covered and obscured from view by dust and smoke from bursting shells, later to be revealed as standing upright and urging the men forward. Colonel Flint's outstanding leadership, personal bravery and zealous devotion to duty exemplify the highest traditions of the military forces of the United States and reflect great credit upon himself, his unit, and the United States Army.

General Orders: Headquarters, Seventh U.S. Army, General Orders No. 25 (1943)

Service: Army

Division: 9th Infantry Division

From Hall of Valor:

The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress July 9, 1918, takes pride in presenting a Bronze Oak Leaf Cluster in lieu of a Second Award of the Distinguished Service Cross (Posthumously) to Colonel (Cavalry) Harry Albert Flint (ASN: 0-3377), United States Army, for extraordinary heroism in connection with military operations against an armed enemy while serving as Commanding Officer, 39th Infantry Regiment, 9th Infantry Division, in action against enemy forces during the invasion of Normandy, France, on 23 July 1944. While advancing on the Saint-Lô-Périers road, Colonel Flint's regiment was held up by heavy mortar fire. Leading from the front, Colonel Fling and a rifle patrol soon found the source of enemy fire. He reported by radio over the walkie-talkie: "Have spotted pillbox. Will start them cooking." Calling for a tank, he rode atop it in a rain of fire as it sprayed the hedgerows. During the attack, the tank driver was wounded, stopping it, whereupon Colonel Flint crawled down, and went forward on foot with his men. As he led the patrol into the shelter of a farmhouse he was hit by a sniper's bullet. He died of his wounds the following day. Colonel Flint's outstanding leadership, personal bravery and zealous devotion to duty at the cost of his life, exemplify the highest traditions of the military forces of the United States and reflect great credit upon himself, the 9th Infantry Division, and the United States Army.

General Orders: Headquarters, First U.S. Army, General Orders No. 75 (1944)

Service: Army

Division: 9th Infantry Division

Silver Star

From Hall of Valor:

(Citation Needed) - SYNOPSIS: Colonel (Cavalry) Harry Albert Flint (ASN: 0-3377), United States Army, was awarded the Silver Star for conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in action against the enemy while serving as Commanding Officer of the 39th Infantry Regiment, 9th Infantry Division, in action during World War II. Colonel Flint's gallant actions and dedicated devotion to duty, without regard for his own life, were in keeping with the highest traditions of military service and reflect great credit upon himself, his unit, and the United States Army.

General Orders: Headquarters, 9th Infantry Division, General Orders No. 32 (1944)

Service: Army

Division: 9th Infantry Division

Rank: Colonel

From Hall of Valor:

(Citation Needed) - SYNOPSIS: Colonel (Cavalry) Harry Albert Flint (ASN: 0-3377), United States Army, was awarded a Bronze Oak Leaf Cluster in lieu of a Second Award of the Silver Star for conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in action against the enemy while serving as Commanding Officer of the 39th Infantry Regiment, 9th Infantry Division, in action during World War II. Colonel Flint's gallant actions and dedicated devotion to duty, without regard for his own life, were in keeping with the highest traditions of military service and reflect great credit upon himself, his unit, and the United States Army.

General Orders: Headquarters, 4th Infantry Division, General Orders No. 68 (1944)

Service: Army

Division: 9th Infantry Division

Rank: Colonel

From Hall of Valor:

(Citation Needed) - SYNOPSIS: Colonel (Cavalry) Harry Albert Flint (ASN: 0-3377), United States Army, was awarded a Second Bronze Oak Leaf Cluster in lieu of a Third Award of the Silver Star for conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in action against the enemy while serving as Commanding Officer of the 39th Infantry Regiment, 9th Infantry Division, in action during World War II. Colonel Flint's gallant actions and dedicated devotion to duty, without regard for his own life, were in keeping with the highest traditions of military service and reflect great credit upon himself, his unit, and the United States Army.

Service: Army

Division: 9th Infantry Division

Rank: Colonel

Legion of Merit

From Hall of Valor:

(Citation Needed) - SYNOPSIS: Colonel (Cavalry) Harry Albert Flint (ASN: 0-3377), United States Army, was awarded the Legion of Merit for exceptionally meritorious conduct in the performance of outstanding services to the Government of the United States while serving as Commanding officer of the 56th Armored Infantry Regiment, 2d Armored Division, during the period from 1941 to 1942.

Service: Army

Division: 2d Armored Division

Rank: Colonel

Other

The "AAA-O" stenciling Paddy directed to be placed on the helmets and vehicles of his regiment were later used in German propaganda.

Book

There was a book written about him: "Paddy: The Colorful Story of Colonel Harry A. "Paddy" Flint" by Robert Anderson.

Toting two carbines, an M-1 Garand, and shouting, "They couldn't hit me anyway," 39th Regimental Commander, "Paddy" Flint-far out in front of even his own pinned-down company-charged through the hedgerows pouring round after round into the tails of a now withdrawing enemy. He had to lead his regiment to the Marigny/St. Lo road crossing to help kick off "Cobra," General Bradley's operation for the Allied breakout of Normandy. The half-dozen German tanks and SS infantry in his way would not stop him from rallying his "Triple A-O" boys and being there on time! This is the story of Col. Harry A. "Paddy" Flint. A 1912 West Point graduate with extensive training and experience, Flint, according to an Army rule, was considered too old to serve overseas as a combat commander in World War II. Finally, with the help of some high-placed friends, such as Gen. George S. Patton, Jr., he was assigned command of the 39th Regiment in Sicily in 1943. There he created the famous battle slogan, "Anything, Anywhere, Anytime, Bar Nothing!" (A-A-A-O). Flint was the embodiment of a born soldier. He inspired many with his courage and valor, and met his destiny in the hedgerows of Normandy. With many never-before-published letters and photographs, PADDY captures the witty, the emotional-the more private sides-of such World War II power players as Generals Patton, Bradley, Eisenhower and others involved in Paddy's colorful life story.

The "category" links below lead to lists of related Honorees; use them to explore further the service and sacrifice of alumni in Memorial Hall.