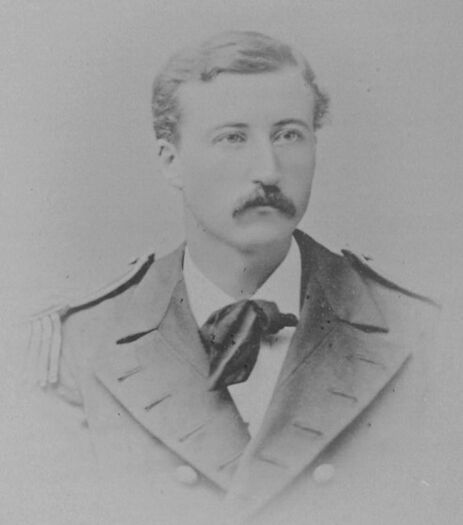

JAMES M. WIGHT, MASTER, USN

James Wight '71

James Marshall Wight was admitted to the Naval Academy from Chicago, Illinois on June 29, 1867 at age 15 years 10 months.

Photographs

Loss

James was lost on November 24, 1877 when USS Huron (1875) went aground and then wrecked in heavy weather off Nags Head, North Carolina. Ninety-seven other officers and men were also lost.

Memorial Book

James was the subject of a hard-bound book, reproduced in full here.

On the morning of Nov. 24, 1877, between one and two o'clock, the United States Steamer "Huron" on her way from New York to Havana, went ashore near Nag's Head on the coast of North Carolina, and was totally wrecked. Of the one hundred and thirty-four persons on board, consisting of fourteen officers and one hundred and twenty marines and seamen, only thirty-four persons escaped, viz: four officers and thirty men. Of the officers lost Master James M. Wight was one; and of him this minute is prepared.

JAMES MARSHALL WIGHT was the third son of Rev. J. Ambrose Wight, of Bay City, Michigan. He was born in Chicago, Ill., on the 31st day of July, 1851. It was in the time when the cholera was raging in the city; and on the day of his birth, Walter Butler, Esq., lay dying of that disease in the house just across the way, on the corner of Fourth Avenue and Harrison street. It was in many respects a time of trial. The father of James was taken sick the same day and was kept in bed for two weeks; and in a few days the hired girl, a Norwegian, and a faithful christian, was struck with typhoid fever: and from the impossibility of her being taken care of in the house, was, by the advice of Dr. Brainard, carried to the City Hospital under the care of the Sisters of Mercy, where in her delirium a few nights after, she got out of the window and fell upon the pavement below, where she was taken up dead. These circumstances come vividly to mind now that James meets his death in so terrible a manner.

He was a fine, healthy child and seldom suffered from any complaint, running the gauntlet of scarlet fever, measles, diptheria and other diseases so often fatal to childhood, with impunity; though the measles left him with some tenderness of sight and hearing.

He began his school life at a branch of the Jones school in Chicago, at the corner of Twelfth street and Wabash Aveuue; whence he was soon transferred to the Mosely school which was situated on Michigan Avenue, a mile and more from his home. Here his attendance was alone. But he always had the good fortune to attract the favor of his teachers; and though but six years of age, and among many rough children, his school life went on at the Mosely till the building of the Haven school house on Wabash Avenue, near his home. His attendance here continued till he left the city, April, 1865. He was now in his fourteenth year, and was qualified to enter the High school.

The life of a boy at that age seldom developes any remarkable trait of character; but a careful observation of the boy James till this time might notice the following things in his make up: For one thing he possessed a degree of self-respect not always seen in boys of his age. The boys of the street were not attractive to him; he shunned them from the first. The few companions that he had were the better lads of his immediate neighborhood, while of the ragmuffins, of which the city was full, he always spoke in contempt.

He had also an inclination to business; he formed a number of partnerships in kite-making and other boyish trades. In the manufacture of kites he was quite skillful and industrious; but it was noticed that the money taken for the kites always went into the pockets of his partners, while the damaged material was his share of the profits.

His unflinchingness and tenacity of purpose came out on an occasion, which might have proved serious. His father had received some three tons of coal late one Saturday afternoon which was to be put into the cellar. In order to do this it had to be wheeled some rods with a wheel-barrow. James proposed to his father that he would put it in its place. He was but eleven years of age, but was strong and could manage a wheel-barrow of coal very well. His father had a call away, and left James at his work, supposing that like other boys, he would work till tired and then stop. But he was surprised on his return after dark to find the lad still at his coal, and just finishing the job; but the boy was exhausted and the next day was taken violently ill of a fever; and without skilfull treatment might have suffered severely. His father thus discovered that James must be limited as to the extent of his work.

In April 1865 the family left Chicago; the father taking them to Oak Creek, Wis., to pay a visit to his sister there; and while he himself went on to Bay City, Mich., where he was called to take charge of the Presbyterian church, the family remained in Oak Creek till his return for them, after securing a residence for occupation in Bay City. On taking the family to Michigan, in August following, young James requested to be left at Oak Creek for the year, that he might learn farm work. His wish was acceded to, and he made his appearance, coming by himself, in Bay City the year following, April 1866. Here he spent the summer assisting his father in getting his new residence in order. He built a barn 16x18 feet, doing all the work of framing, covering and painting; also a fence around the lot; finished the garrets, and all in a workmanlike manner, and adhering to his task with the steadiness of a man at wages. Many of the people of Bay City remember his fidelity, ingenuity and industry.

In the autumn he signified his wish to renew his school life; and he spent the winter at the public school; Professor Wells being the principal; his studies including the Latin language. His progress was excellent and his fidelity to study unimpeachable. In the month of June, 1867, he astonished his • Father by saying that he wished to enter the Navy. He had seen in the city paper a notice by Hon. John F. Driggs, M. C., appointing a commission to examine competitors for a situation in the Naval Academy at Annapolis; the commission to meet at East Saginaw, June 1867.

His examination before this commission is thus described, in a letter from Mr. Driggs written to the Saginaw Courier after the loss of the Huron:

EDITOR COURIER.—The sad incident of the loss of the U.S. ship of war, 'Huron,' and the sacrifice of about one hundred officers and men has filled the hearts of many with mourning. When the painful news reached this city I felt much anxiety to learn whether any of my appointees to the naval academy were included among the lost; and among the list of officers who perished (as published in the Courier to-day) I am pained to read the following: 'Master James M. Wight is a native of Bay City, Mich., and was appointed July 1, 1867, by Hon. John F. Driggs, He graduated in June, 1871 and was promoted June 20, 1876.' Some years ago when I had a vacancy to fill, I appointed a commission of able gentlemen, consisting of Prof. Estabrook and others, to meet in the high school in this city on a certain day to make a selection. Having previously published the time, place and mode of selection, a large number appeared in competition and presented their letters to me. These letters with their names I handed to the Board. Just as they met to consider each case, a small boy came to me from Bay City. He was well built and appeared very quiet and modest. He handed me but one letter and that was from his father. As well as I can remember it read as follows:

The bearer is my son; he has for some time importuned me to consent to have him strive for a cadetship. I am unable to furnish much for his outfit or expense, but have at last consented to let him try, and though I hope he may succeed, I have but little faith in his success. Hoping he may have an equal chance with the rest, I am very truly yours, -------

Though there were several, and especially one of this city, who stood high in school, that I hoped might succeed, still I gave no intimation of preference to the Board and declined to visit them till they had made their selection. But I went immediately with this lad, introduced him to the Board and presented his case and came away. The gentlemen made a selection and brought me a copy of questions and answers. This boy rivaled them all and I appointed him. The next day he called on his way to Annapolis with nothing but his carpet bag. I gave him a good letter to Commodore Porter in charge and the boy thanked me and left. I bade him good bye with many kind words. I subsequently learned from a lady whose son I had previously appointed and who was on a visit there when Wight came to Annapolis, that Commodore Porter was absent and she told that this little fellow, instead of going to the receiving ship went to the Commodore's house and in his absence his lady received him very kindly. On account of his modest and quiet bearing she kept him all night and soon became attached to him. In the morning the Commodore took him to his quarters and kindly cared for him. Suffice it to say that his attention and proficiency was such in the academy that he graduated with credit to himself, his father and all interested. He entered the navy and was promoted. When he perished at his post he ranked as Master in the navy. He was the son of the Rev. Mr. Wight, then and it still may be a resident of Bay City. In common with his relatives and friends I mourn the untimely loss of this worthy young officer." J. F. DRIGGS. East Saginaw, Nov. 28, 1877.

His selection by this committee was a surprise to his father, and was regretted by him on many accounts, but was acquiesced in, from the following considerations: It was desired by him that James should be afforded chances for a better education than the public school at Bay City afforded at that time, but the means were wanting to send him abroad. The conditions of the naval academy were, that the pupil should be educated at the national expense; and as an offset, should engage to serve the nation four years after graduation, when he might honorably resign if dissatisfied with the service. James would be, at the end of eight years from his entrance at the academy, twenty-four years of age; young enough for a profession or a business, if it were his wish. It was distinetly considered, that the naval service involved perils both to life and to character; so does service anywhere, in any line of life; and if God led him by His providence into that service, he could as easily protect him there as anywhere. Besides, we had recently come out of our great war, and the naval service, as well as that of the army, had assumed a new importance in the public mind; not only in a political but a religious point of view. And James' older brother, Ambrose, had served in the navy for a year and a half during the war; and though engaged in a battle upon the "Elfin," at Johnsonville, Tenn., with the Confederate forces under Ned Forrest; and though encountering small pox, yet escaped it, upon the "Cincinnati" where twenty-six cases of it occurred; and though spending weeks in Mobile harbor, sailing over the torpedoes with which the Bay was peppered, he still came home in safety, both in character and health. It was remembered too, that the lads who went from his church in Chicago to the war, some of whom served three years; that they returned stronger and better young men than they were when enlisting. The reasoning was, that if God called the lad to the naval service, He might have important work for him in after years, in the interests of his country.

With such considerations as these, James was fitted out and sent to Annapolis, having railroad ticket and money for return if not accepted. He was small for his years, being fifteen years and ten months of age, and weighing ninety-seven pounds. He made his way to Annapolis alone, in June, 1867; it being vacation there, armed with letters of recommendation and Mr. Drigg's certificate of nomination. Capt. S. B. Luce was in charge of the academy at the time and James sought him at his residence. The captain being absent for a few days, and Mrs. Luce seeing a little fellow satchel in hand, from the window, went to the door; and, being pleased with the intelligent and gentlemanly ways of the lad, called him into the house and bid him make his home there till the captain's return. This kindness of the good lady, in this crucial time of the lad's life was always remembered by James with gratitude, and will continue to be so remembered by his many friends.

His examination a few days after proved satisfactory, though his weight fell three pounds short of the requirement for his years; but James related that he informed the committee, that he had just dug a cellar for his father, and *he thought that went for the three pound deficiency." He was thereupon assigned to the receiving ship "Constitution," then used as a training vessel for the lowest class, called at the institute "Plebs." The class consisted of ninety-three members, of whom forty eight graduated in 1871. In this class of forty-eight James ranked thirty-four. On the aggregate merit roll, whose maximum is one thousand five hundred and thirty-seven, his mark at his graduation is one thousand and two and two-tenths, or nearly two-thirds of the maximum. Of those who ranked above him, some had the advantage of him in age; a number had spent five years instead of four at the academy; some increased their average by a decided superiority in a few studies, and there was a genius or two, who in such institutions always sweep the board. An examination shows that James' range or plane of performance was remarkably even. He makes no ten strikes; but sustains himself well in the whole range. He would have stood better in his class, had he possessed a good faculty of recitation. The want of this lowered his average, and especially in the languages, where so much depends on good recitation. His understanding of the French and Spanish tongues was good, as he had occasion to know when visiting the countries where they were spoken, but his want of eloquence caused him to rank low in them. Upon his examinstion for Ensign he made again of some five numbers.

Considering all the circumstances, his standing in the academy was entirely satisfactory to his friends. His father did not wish him to aim at star scholarship, had he been able to reach it, well-knowing the perils of such a position.

His different cruises while in the academy were to the island of Madeira upon the "Macedonia" in the summer of 1868; to Liverpool on the "Savannah" in 1869, and to Cherbourg in 1870; from Liverpool he visited London, and from Cherbourg, Paris. In all these cruises he indulged a native fancy for picking up curiosities; a habit which he held to as long as he lived, so that he became possessor very soon of a considerable cabinet of rare products from different quarters of the world.

He visited his home, twice during his academical term; first in the summer of 1868, and again in 1870. After graduating in June, 1871, and a brief visit home, he was ordered to the U. S. S. "Iroquois" which was expected to be sent to Chinese waters and attached to the Asiatic fleet. But it pleased the Russian government to send, that year, Duke Alexis, son of the Emperor, to this country, for an airing; and the U.S. Government, being on excellent terms with the Russian Government, assigned a part of its fleet, the "Iroquois" included, as a convoy of welcome into the city of New York. Upon this business the "Iroquois" was kept waiting for some six weeks before the Duke came in sight; the idea being, the longer the waiting the greater the honor.

This business being disposed of, and the "Iroquois" needing repairs, James was transferred to the "Canandaigua," whose service for the coming year was in the Gulf of Mexico and the waters of the West Indies. The great peril of this service in the summer season is sickness. The customary fevers visited the "Canandaigua," yellow fever included, though in its milder form, so that the surgeons were able to call it by another name, and thus save the fears of the crew. Some seven cases of it occurred however and the following season it broke out upon the "Canandaigua" with such force that the vessel was hastily sent north, and continued there for the season.

In the autumn of 1872 James was attached to the "Hartford" in its voyage to China. The vessel passed through the Suez Canal and Red Sea. In the latter waters he affirmed that he saw the place "where Pharaoh was swamped." The first part of this fourteen hundred miles of water was passed very pleasantly; but at the southern extremity the usual simoon was encountered, which made the rest of the voyage difficult, the "Hartford" not obeying her steam works well. The cost of getting the "Hartford" through the canal was $471, in toll.

She touched at Aden, and then at the little Isle of Socotra. Here several of the young officers seeing no surf running obtained leave to go ashore. Their stay being longer than anticipated, they found the surf running "twenty feet high" on their return, and the boat waiting outside for them, unable to get in. 'There was no resource for them but to swim the surf; which proved a difficult and dangerous undertaking. James was caught and tumbled about among the rocks, and only succeeded after a number of trials in reaching the boat. The effort came near being fatal to him, being succeeded by pneumonia, so that for a time his life was despaired of. The fate which he escaped overtook a fellow midshipman. James H. Winlock had been in poor health, but was getting along very well until overtaken by the extreme heat in the vicinity of Singapore; and according to the custom of the officers, seeking coolness during the nicht wherever it could be found, he had laid himself down upon some canvass on deck, where, falling asleep in the draft he was taking with a congestive chill and before being discovered was too far gone to rally, and died the next day. He was landed and buried on the shore at Pulo Penang, where a monument erected by his shipmates marks his grave.

Soon after reaching Japanese waters, James was transferred to the "Lackawana," March, 1873; upon which he was continued about a year; and this vessel he regarded as one of the pleasantest on which he had service before or afterward. This vessel visited all parts of the Chinese and Japanese waters, cruising northward to the Chinese wall, a stone of which he secured and brought home; and to Vladivastok in the Russian possessions.

From the "Lackawana" he was put upon the "Palos," April, 1874, a very small affair, but a good sailor. Upon crossing from Nagasaki to Shanghai it encountered a typhoon, and for some twelve hours had a prospect of going to the bottom. In the summer of 1874 he was ordered home for examination, with a view to promotion. He came by San Francisco, making the voyage very briefly; and in strong contrast with the six months outward passage on the "Hartford," and thus circumnavigating the globe. Some two months of waiting orders gave him opportunity for study in preparation for his examination, this being a erucial one. He passed it in December, 1874, and gained an advance of five numbers; but failed to do quite as well as he hoped in seamanship. Upon this study he had laid himself out, intending to shine in it, but over did the matter by sitting up all night previous, and so exhausted himself that his recollection nearly left him. Still he passed with credit and was made an Ensign.

Having the prospect of long waiting orders, and perhaps a re-appointment to the Gulf Squadron, he applied for a position in the Coast Survey and was assigned to the "Bache" under charge of Lieut. J. M. Hawley. This vessel was to make a winter voyage from New York to Savannah. The voyage was accomplished by taking the "inside passage" for a good part of the way, but with a great deal of difficulty and considerable danger. The Savannah river had never been surveyed with any thoroughness, and during the war was able to baffle the U. S. vessels desiring to enter it. The "Bache" accomplished the work very perfectly, finishing it about the last of May, 1875. But it proved a damaging business to James; the spring was very hot and the sun overpowering. Working in an open boat, day after day, with the mercury at one hundred degrees, the glare upon the water came near producing a total blindness with him. Medical help and employ on the coast of Maine during the summer, where the fog prevented out door work for near, four-fifths of the time, went so far to restore him that his sight was preserved; but he deemed that service too perilous to be continued, and returned to the Navy proper in the autumn of 1875. He reached the rank of Master June, 1876. His appointment now was to the Monitor "Saugus" lying at Pensacola, neglected and going to decay. Service upon this class of vessels is not deemed desirable by naval officers. They are sunk mostly in the sea, and the heat below is oppressive; the mercury upon the "Saugus" standing at one hundred degrees in the ward room, and one hundred and thirty four degrees in the engine room as a very common thing. The officer in command of the "Saugus" was not in good repute with his fellows, and the service under him was by no means pleasant: but James so conducted himself as to gain official commendation. The "Saugus" made the voyage from Pensacola to Port Royal, S. C., around the Florida capes, and though under water a fair part of the time, she came safely through one of the longest voyages ever accomplished by this class of vessels.

In August James was ordered home on waiting orders, and put upon furlough pay. The explanaation of this was, that it was Presidential year and the lower House of Congress was taken with a fit of economy, and cut down appropriation to such a figure that the Army and Navy both had to go unpaid, in whole or in part. The younger officers of the Navy were therefore sent home for the summer, and their pay reduced two-thirds. By a deficiency bill, it was subsequently restored, so that "waiting orders" pay was finally realized. His stay at home was prolonged till February 1877, when he left it for the last time, being ordered to the receiving ship "Colorado" at the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

His time at home was divided between study and bracket making; by means of a scroll sawing machine some very excellent work of this sort is left to attest his mechanical ingenuity. From the "Colorado" he was ordered to the "Supply," a training vessel, in May, 1877; and on this vessel the summer was pleasantly spent along the Itlantic coast, having in charge something like one hundred lads picked up in cities, of whom the government was making sailors for the navy. The "Supply" went out of commission in September and James was transferred to the "Huron," an iron vessel, destined to some surveys in Caban waters during the winter. The "Huron" was a new vessel built at Chester, Pa., according to an act of Congress passed in 1873. She was of third class, considered stanch for sea-service, though slow of motion. To remedy this a new screw was put in at the navy yard, and other repairs, a fore-mast included, were made; so that she sailed in good order from New York in November, calling at Norfolk and Hampton Roads, on the seventeenth of the month. Here she coaled, was inspected by the Admiral, and sailed from Hampton Roads on the twenty-third, expecting to call at Key West and finish coaling. James' last letter was dated, Hampton Roads, Oct. 22, and it reached Bay City the twenty seventh, three days after his death. In this letter he directs that letters be addressed to him at Havana, in care of American consul.

The Huron sailed at eleven o'clock, A. M., the twenty-third, Commander Geo. P. Ryan in command, with fourteen officers and one hundred and twenty sailors and marines. As night came on, the wind rose, and the weather became gradually very heavy, with some fog. James was on watch from eight to twelve; after that Master Walter S. French took the deck. In an hour and ten minutes the vessel thumped, and continued thumping till about 1:30 A. M., when she stuck fast and careened over, lying at an angle of forty degrees with the shore; though the shore was not visible, and much doubt prevailed among the officers as to their whereabouts. The thumping brought the officers immediately to the deck; but it was found impossible to fasten down the hatches, or lower the sails, or get overboard the guns, though orders were given successively for these things. As the vessel struck, her boilers were moved and her upper works more or less displaced; and the sea breaking over her, men began to be washed overboard. Signal rockets were sent up and the whistle sounded in token of distress, but no help came from the shore at that or any other time. The vessel began to break up at once and part; the tide coming in and increasing the depth and volume of water, and the distance from land. All testimony is that the officers were cool and the men obeyed orders as long as system or order was attainable; but some went ashore for assistance and others were continually washed off, till a little after 7 o'clock in the morning of the twenty-fourth all had left the vessel. Four of the officers were saved and ten lost; of the men, thirty escaped and one hundred perished. The information obtained concerning James from the time of the wreck is but little. The four officers who escaped are Ensign Lucien E. Young. Master W. P. Conway, Cadet Engineer E. T. Waburton and Assistant Engineer R. G. Denig. Of these, Ensign Young came ashore early and saw little of the other officers. Mr. Waburton writes:

I saw Mr. Wight about 3:15 A. M., two hours after the vessel struck. We were at that time below, where we had gone to put on dry clothing. As he was returning on deck he showed me his ring, and remarked that it would be all he would save besides his pocket book. I was with him again a half hour afterwards in front of the cabin; he was all this time in good spirits and I am sure confidently expected to be saved. I was washed off the ship about seven o'clock, and as I was going I passed by him; he was hanging on the starboard fore chains. He was a good officer, akind friend and a pleasant messmate."

In another letter Mr. Waburton adds to the above:

After we were on deck Mr. Wight and I staid under the poop deck until we were obliged to move forward. I did not see him again till the minute before I was washed away, when I saw him seated by Lieut. Simous in the starboard chains. They both looked weak and I fear neither held out long after I left.

Mr. Wight was a popular officer aboard ship and much liked by all.

Mr. R. G. Denig, Assistant Engineer, writes:

Mr. J. M. Wight was a true man, a good shipmate, a valued, zealous officer. I recollect him long after the ship was stranded, striving to his utmost both by example and command to carry out the last orders of the captain; indeed he did not leave the deck, working harder and longer than any officer of the ship. My last speaking with him was a few short sentences between the heavy seas that drenched us, regarding the guns which he was endeavoring to cast overboard. He made a strong effort to lower the sails, so instrumental in causing the fatal disaster; and in every way he was devoted to duty until the last. When the ship was filled with water all discipline was at an end, and everyone struggled to reach a spot of at least temporary safety, to wait fordaylight. After daylight I saw him in the fore chains; he was unprovided with a life protector, as was every officer. Why I know not, for many of the men had them; at last I missed Mr. Wight, and at the same time Mr. Simons.

Ensign Jesse M. Roper, who spent the summer on the "Supply" with James, and who was assigned to the "Fortune" at the same time James went to the "Huron," visited the scene of the wreck to learn the fate of his companions. He says:

I talked with a man who said that Master Wight was washed away from the forward part of the ship and clung to a spar. At that time he was in company with Lieut. Simons. Some men in attempting to save them were in great danger; and that they finally told them to give up the effort and that they would take their chances of floating ashore.

This is confirmed by Wheelsman E. P. Traver who affirms that he was the one thus described. In addition to these commendations of his fellow officers that of Thos. S. Plunket, who was a room-mate with James in the academy, may be added here.

He was a sterling man, a zealous officer and a desirable companion. We, his class-mates will always recognize in his untimely end a great loss to our ranks. We know that one of the most promising in our number has stood his last watch on earth, and we earnestly hope has received an abundant entrance into the upper and better kingdom.

From these accounts put together it is evident that James, after his four hours watch in the increasing gale from eight to twelve, had been "turned in" about an hour, and had perhaps just fallen asleep as the "Huron" began to pound; that with the rest he rushed upon deck and went to work to clear and save the vessel, till this became hopeless, and then save the men, till that was hopeless also.

Lieut. Simons was the commanding officer after Commander Ryan was washed overboard, which seems to have been early; and James kept near to him and they perished together, leaving the ship or being washed from it among the last, and after seven o'clock. They evidently awaited help from the shore, and were of course exhausted by work, watching, exposure and cold; and doubtless perished quickly on going into the water.

This theory is confirmed by a report of a conversation by one who heard it, between James and a friend, only a few days before his death; being in fact the Monday of the same week. While waiting the cars at Hornelsville, N. Y., where he had spent the Sabbath, the conversation turned upon the matter of wrecks; and the friend asked him what he would do in case of one; observing, that for himself he should look out for number one, get a life preserver, put it on and get ashore as soon as possible. James replied that he would thereby subject himself to court martial for cowardice and neglect of duty in case he should get ashore. For himself, he should put on no life preserver nor try to get ashore as long as anything could be done. His aim would be to save the ship, and he should stay upon it till that hope were gone, and if necessary go down with it. My reading leads me to the conclusion that such is the stuff of which heroes are made: and that while the U. S. navy has such officers, she need not be ashamed whether her vessels are first of third class; but she can ill afford to lose such men.

Of those who perished ninety-one bodies came ashore, those of ten officers included. Four officers, James among them, were not found; they doubtless floated to sea and sank; their burial place being the Atlantic ocean. The body of Lieut. Simons came ashore early, and he was buried from the navy yard, New York.

The officers saved were, as already said, W. P. Conway, Master; Robert G. Denig, Assistant Engineer; Edgar T. Waburton, Cadet Engineer, and Lucien E. Young, Ensign. The officers lost were Alfred Carson, Machinist; Geo. S. Cathbut, Surgeon; F. W. Danner, Ensign; J. J. Evans, Draughtsman; Walter R. French, Master; D. L. Garvin, Captain's clerk; Edward M. Loomis, Cadet Engineer; Edmund Olsen, Chief Engineer; Lambert E. Palmer, Lieutenant and Navigator; Geo. P. Ryan, Commander; Cary N. Saunders, Passed Assistant Paymaster; Sidney A. Simons, Lieutenant, and James M. Wight, Master.

In addition to the loss from the "Huron," a boat from the wrecking steamer "Baker" containing eight persons, was capsized in the surf, and four of the eight persons, including Capt. Gutheric, Paymaster, were lost.

The Huron" did not reach the shore, but struck upon the outer bar, about two hundred and fifty yards from land. This bar is a quicksand through which a strong vessel may drive its prow; but it is full of wrecks and it is thought that the "Huron" struck one of these, the "Ariadne," near which she finally brought to. She struck the bar too, diagonally, and her engines had been backing for some time. Had she driven prow first upon the bar she would probably have gone through it, and would have found comparatively still water inside it, besides being close to shore; and in such case few would have perished. It was also low tide and the force of the surf was spent on this outer bar. But the land is only a sand beach between the ocean and Albemarle sound.

As is the case where wrecks are frequent, few efforts for relief were made by the people on shore; though her calamity was known from the first. A fisherman at Nag's Head saw her coming ashore at 1:30 o'clock; he saw the rockets, and by their light the men on the vessel. The keeper of the life-saving station lived two miles and a-half away, and the fisherman could have reached him in half an hour; but did nothing. It was nine hours before the officer was notified. The bodies that came ashore were also stripped of every article of value, so that no ring even was left upon the fingers of any of them. Watches, money and jewelry were stolen by those who took care to find them before their fellows. The hand of Lieutenant Simons shewed the marks left by pulling his ring from his finger. The sea and the land are often alike cruel to the ship wrecked.

The accusation does not however, lie against all. The sheriff of Dare county, by the name of Binkley, living near, gave all possible succor to the survivors; and a few others drew them out of the surf and assisted them to clothes and shelter.

A court of inquiry was at once convened at Washington by the Navy department, and all the survivors examined. After thorough scrutiny their finding was made up. The substance of it is as follows, viz: That soundings were taken every hour of the night of the twenty-third and twenty-fourth of November, but that there is some discrepancy as to the depth of the water. That the ship had been duly inspected at Hampton Roads by a board of officers appointed by Admiral Trenchard, who reported the ship in good condition and ready for sea in all respects; that she sailed for Hampton Roads by permission of the admiral and the order of her commander; that there is no signal station at Hampton Roads; that she sailed at 1:25 P. M. of the twenty-third of November, Cape Henry light bearing west by south, at the distance of six to seven miles; that the bearing of Currituck light was taken at 6:45 P. M., distance seven to eight miles; that the light was in sight at mid-night; that the lookouts were stationed and vigilant; that after she struck, the conduct of officers and men was admirable; that no complaint is made of any surviving officer or man.

'The court says, every officer in command of a ship is in supreme command. He is responsible for her course. The court is therefor of the opinion that Commander Ryan is primarily responsible for the grounding and loss of the "Huron". The navigating officer is also responsible for not taking bearings to Currituck light after passing it and while it remained in sight, which, by showing the direction from a fixed point, would have established the "Huron's" proximity to land. It was his duty to take such bearings even though not ordered by the commanding officer. The court does not find that any other officer or man is responsible for the loss of the "Huron," except possibly that the officers of the deck may not have personally inspected the soundings and seen that the depths reported were the perpendicular depths obtained. The soundings of this part of the coast, the court says, are so irregular that depths less than twenty fathoms can give no reliable information in regard to position or distance from shore. The court find the "Huron" to be a well-formed, stanch, sea-worthy vessel. The court does not consider that a seamanlike attention and precision were given to either soundings or bearings taken; that no sufficient allowance was made for the inset towards the coast; and that the course steered was from error of judgment, too much to the southward; with due caution and by carefully taken and plotted bearings of Currituck light, the close proximity of the "Huron' to the coast would have been manifest; and that it was unseamanlike to carry sail on a lee shore; the sails lifting, and the natural desire to keep them full, probably inducing the quartermaster to run leeward of his course, and the lifting sails having a tendency to drag the vessel to leeward.

The object of this paper is not the eulogy of the deceased. It is fair, however, that his commendable traits should be mentioned. James had the good fortune to be a favorite among his acquaintances. All persons who saw him formed a favorable opinion of him. This was due to a distinctness of character, self-possession, modesty and gentlemanliness; but connected with a decided integrity of character, which was very remarkable. He believed in truth and honesty, and hated sham, shirk and evasion. He scored the endeavor to pass himself for more than he was. He believed in and practiced a straight-forward adhesion to duty, and would die sooner than flinch. He had never made a profession of religion; but proposed, after his return from the cruise of the winter, to do so; deeming a christian life the necessary climax of a true character. His command of self was very remarkable; nothing would induce him to violate a rule which he had laid down for himself in matter of appetite or self indulgence. The vices to which young men so often succumb were all unknown to him.

The loss of such an one, to his own family cannot be stated; for a wound to affection is not a thing for exhibition; but his loss to his country, is a distinct thing. It costs the government, to educate a naval officer, some forty-thousand dollars. A good officer is therefor of great value. It is by the navy that our government is known over the earth; and is able to protect the lives and interests of her thousands of citizens, abroad, for travel, business or religion. A good naval officer is a price of inestimable value.

Had James lived, it is safe to conclude that he would have been heard of in after days. He had the qualities and the disposition which win in the long race. He might or might not have taken a first rank on the naval register; but he would have taken a first rank as an officer to be trusted in and esteemed.

Nor has he lived in vain. His influence has been genially and healthfully felt in all the circles where he has moved. And to God's mercy, whose covenant embraced him, he is prayerfully, sadly, yet trustingly committed.

Obituary

From “Class of ’71,” a book published in 1902:

JAMES MADISON WIGHT was born in Chicago, Illinois, on July 31, 1851. His parents were Jay Ambrose Wight and Caroline Adams Wight. He received his earlier education in the public schools of Chicago and Bay City, Michigan. He was appointed to the Naval Academy from Bay City, Michigan, by the Hon. John F. Driggs, representing that Congressional District, and entering the institution in 1867, graduated with his class on June 6, 1871.

His first duty after graduation was aboard the U. S. S. Iroquois, forming part of the Reception Fleet appointed to receive the Grand Duke Alexis of Russia. After this squadron was dispersed he was ordered to the U. S. S. Canandaigua, on the North Atlantic Station, and on this vessel went to the Gulf of Mexico. Yellow fever broke out on the vessel and she was ordered north. Wight was ordered home, and after a short leave of absence was ordered to the U.S. S. Hartford, and proceeded in 1872 to the Asiatic Station, via the Suez Canal, arriving in Japan in the latter part of 1872. He was in 1878 transferred to the U. S. S. Lackawanna (March, 1878) and served aboard that vessel until April, 1874, when he was transferred to the U. S. S. Palos.

In the fall of 1874 he was detached from the Palos and ordered to return to the United States. He passed his examination for promotion to Ensign, and was in December, 1874, ordered to duty in the U. S. Coast Survey, being assigned to the Bache, under command of Lieutenant J. M. Hawley, U. S. Navy. While in the Bache he was engaged in surveying the Savannah River. In the autumn of 1875 he returned to the regular naval service and was ordered to the U. S. Monitor Saugus, where he continued until February, 1877, when he was detached and ordered to the Receiving-ship Colorado. In May, 1877, he was transferred to the Training-ship Supply, and after a short cruise on that vessel was ordered to the U. S. S. Huron, which ship was wrecked on Nag’s Head, North Carolina, on the 24th of November, 1877.

He was unmarried at the time of his death. He has one sister living, Mrs. Julia W. Cooke, of Bay City, Michigan.

From Army & Navy Journal on December 15, 1877:

James M. Wight, Master, U.S.N, who perished in the Huron, was the third son of Rev. J. Ambrose Wight, D.D., pastor for twelve and more years, of the Presbyterian Church, of Bay City, Michigan. He was born in Chicago, Ill., July 31, 1851; and remained there till the removal of the family to Bay City, April, 1865. His early education was in the excellent Public Schools of Chicago; and he was prepared for the High School at the time of his removal. After a year in Wisconsin, he joined his family in Bay City, and attended school there till June, 1867, when he was recommended to the Naval Academy, at Annapolis, by Hon. John F. Driggs, M.C., after a competitive examination, by which he was unanimously selected. His appearance before this committee was as a stranger and alone. He made his way also alone to Annapolis, where he was accepted. The Navy was his own choice, and the way into it was singularly and unexpectedly opened to him.

He graduated in 1871, and was assigned to the Iroquois, while that vessel was acting as convoy to the Grand Duke Alexis into New York. From the Iroquois he went to the Canandaigua, and served the season with the Gulf Squadron. The following year he was sent to Chinese waters, on the Hartford; and was there about two years, first on the Lackawanna and then on the Palon. He returned in 1874 for examination and promotion, and became an ensign, his commission dating back one year. He spent the '75 in the coast survey on the schooner Bache, in a survey of the Savannah River and up the coast of Maine. His eyes being weak for that service, he was detached to the monitor Saugus, upon which he made the passage from Pensacola to Port Royal around the Florida Capes. He became master in 1875.

The summer and autumn of '76 were spent at home "waiting orders;" but in Feb., '77, he was ordered to the Receiving ship Colorado, and from that to the Supply, upon which summer was spent. His assignment to the Huron was in September. He was 26 years and four months of age, and his service to the Government, counting time at the Academy, about ten years.

Officers associated with him in the Navy know of his official standing and value better than anybody else. His friends at home know him as a young man of rare integrity of character; free from the vices which beset young men; self-governing and conscientious, and devoted to duty. His attachment to the naval service was intense. He knew the dangers of it as well as anybody, for he had been several times near to death; and notedly at the Isle of Socotra, on the voyage of the Hartford, where going ashore with a party, on their return they found the surf high, and the boat waiting outside it, unable to get in. They were forced to swim, and young Wight was caught and tumbled about among the rocks; and, after going to the vessel, came near dying from the effects. His friends would bear the loss now with more content, did they feel that it was a necessity.

He has Find A Grave entries here and here.

Career

From the Naval History and Heritage Command:

Midshipman, 1 July, 1867. Graduated 6 June, 1871. Ensign, 14 July, 1872. Master, 30 June, 1873. Lost on Huron, 24 November, 1877.

The "Register of Commissioned and Warrant Officers of the United States Navy and Marine Corps" was published annually from 1815 through at least the 1970s; it provided rank, command or station, and occasionally billet until the beginning of World War II when command/station was no longer included. Scanned copies were reviewed and data entered from the mid-1840s through 1922, when more-frequent Navy Directories were available.

The Navy Directory was a publication that provided information on the command, billet, and rank of every active and retired naval officer. Single editions have been found online from January 1915 and March 1918, and then from three to six editions per year from 1923 through 1940; the final edition is from April 1941.

The entries in both series of documents are sometimes cryptic and confusing. They are often inconsistent, even within an edition, with the name of commands; this is especially true for aviation squadrons in the 1920s and early 1930s.

Alumni listed at the same command may or may not have had significant interactions; they could have shared a stateroom or workspace, stood many hours of watch together… or, especially at the larger commands, they might not have known each other at all. The information provides the opportunity to draw connections that are otherwise invisible, though, and gives a fuller view of the professional experiences of these alumni in Memorial Hall.

January 1871

January 1872

January 1873

January 1874

January 1875

January 1876

Related Articles

George Ryan '61, Sydney Simons '67, Lambert Palmer '68, Walter French '71, Frederick Danner '74, and Edmund Loomis '75 were also lost when Huron was wrecked.

James is one of 3 members of the Class of 1871 on Virtual Memorial Hall.

The "category" links below lead to lists of related Honorees; use them to explore further the service and sacrifice of alumni in Memorial Hall.