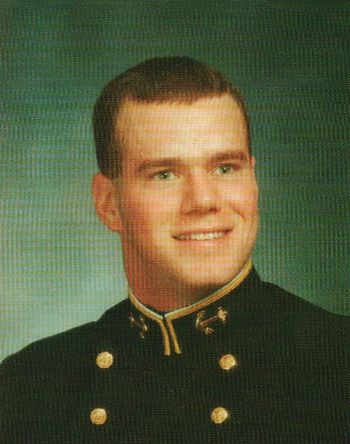

JAMES P. BLECKSMITH, 2LT, USMCR

James Blecksmith '03

Lucky Bag

From the 2003 Lucky Bag:

James Patrick Blecksmith

San Marino, California

I-Day, 6th Art. of the Code of Conduct, scout team, Hawai'i- almost got in, 8 weeks of Chem2/Calc2, YP's- techno sushi, gourmet cooking FF-8 USS McINerney- Daytona, "I will not let my people down!", $2, Leroy, "You better Belize it!", "I'm gettin' a Bad Az!", Stinky Rank, Chesty Fuller, Angry, Chody, Bad Az- Setts with Zetts/Body by Blecksmith, Disco Ray- D.C weekend, Armidillos- $150 tab, Belize- Pass me another Belikin!, PUT IT BACK!, NYC after Army game, trapped in Chicago, Popeye the Dirty Sailor Man, somehow got through classes, Beastman - you furry fool!, FB- QB, FS, OLB, GS, QB/WR, WR. .?? "You don't know nothin' bout that!". . ."I have only a second rate brain, but I think I have a capacity for action." -Teddy R., "Nil mortalibus ardui est." -Horace

James Patrick Blecksmith

San Marino, California

I-Day, 6th Art. of the Code of Conduct, scout team, Hawai'i- almost got in, 8 weeks of Chem2/Calc2, YP's- techno sushi, gourmet cooking FF-8 USS McINerney- Daytona, "I will not let my people down!", $2, Leroy, "You better Belize it!", "I'm gettin' a Bad Az!", Stinky Rank, Chesty Fuller, Angry, Chody, Bad Az- Setts with Zetts/Body by Blecksmith, Disco Ray- D.C weekend, Armidillos- $150 tab, Belize- Pass me another Belikin!, PUT IT BACK!, NYC after Army game, trapped in Chicago, Popeye the Dirty Sailor Man, somehow got through classes, Beastman - you furry fool!, FB- QB, FS, OLB, GS, QB/WR, WR. .?? "You don't know nothin' bout that!". . ."I have only a second rate brain, but I think I have a capacity for action." -Teddy R., "Nil mortalibus ardui est." -Horace

Obituary

From The Los Angeles Times on November 28, 2004:

James P. Blecksmith was only 24 when he died. But by age 16, he already was displaying the quiet altruism that made him a natural as a Marine Corps officer, family members said.

"He led by example. He lived his life the way he talked about his life," his sister, Christina, 27, said at the family home in San Marino.

The second lieutenant, a U.S. Naval Academy graduate, was killed by sniper fire Nov. 11 in Fallujah, Iraq.

Blecksmith, who went by the nickname J.P., was a gifted athlete at Flintridge Preparatory School, family members said. His brother, Alex, 25, recalled being on the same track team when he was a senior and J.P. was a sophomore.

"During league prelims, I failed to qualify and he did. I was really upset with my poor showing," his brother said. "He told my dad he would give up his spot in the league relay so I could run for him."

As it happened, another relay spot opened up and both boys got to run. From that race, J.P. went on to become league champion in the 400-meter relay.

"He was 16 years old, and it was not about his ego or his glory," his brother said. "It just shocked me that he was willing to give up his place. That was the first time I realized he was not just my brother, he was my best friend."

Blecksmith's sister said such humility epitomized his personality. "It's the way J.P. was," she said. "He was a leader. He fought alongside his Marines. He didn't expect them to do anything he wouldn't do."

The Department of Defense told the family that Blecksmith, a platoon leader, was clearing houses of possible insurgents when he was killed. The events were still being pieced together, his sister said, but two of Blecksmith's men reportedly were wounded and, after getting them to safety, he was shot while rechecking the house.

"He was on the roof -- apparently they start with the roof and work their way down," his sister said. "He was shot in the shoulder. The bullet missed his flak jacket but a bone fragment pierced his heart. He died instantly."

Friendly and outgoing, Blecksmith was known as a "big man on campus" in high school, said his brother, who estimated that 1,500 to 2,000 people attended the Marine's funeral Nov. 20.

Blecksmith loved to travel. He took spring break trips with schoolmates to Italy, Spain and Greece. One year, he went to Costa Rica to help build a school and do other community projects.

Blecksmith was heavily recruited by Pac-10 schools because of his talent as a football quarterback, family members said. But his heart was set on going to the Naval Academy and becoming a Marine, like his father. "We have a long line of Marines in our family, and it embodied what he believed," his sister said.

At the academy in Annapolis, Md., he played wide receiver on the football team before graduating as a commissioned officer in 2003.

Blecksmith left for Iraq on Sept. 10 as a member of the 3rd Battalion, 5th Marine Regiment, 1st Marine Division, 1st Marine Expeditionary Force at Camp Pendleton. "He wanted to be in Iraq. He had a job to do, and he was doing it 100%," his sister said.

He called home, wrote letters or e-mailed the family at least once a week. His last conversation with his sister and other family members took place a few days before his death.

"He was definitely kind of reflective," his sister said. "He was worried about his men. He always said he just wanted to be the best leader for his men, and he wanted them to do a good job. He wanted his men to come home safely. And now they will come home safely."

In addition to his brother and sister, Blecksmith is survived by his parents, Edward and Pamela. He was buried at San Gabriel Cemetery.

He is buried in California.

Memorials

The Marine Corps Reserve Center in Pasadena, CA was named for J.P. on Veterans Day, November 11, 2006.

Remembrances

The CBS introduction video for the 2016 Army-Navy game included repeated mention of J.P.

From the Naval Academy Alumni Association's "In Memoriam" page:

He did everything that a father could ever want or ask of a son. Ed Blecksmith

From Medium on November 11, 2014:

Leave No Man Behind

But the soldier’s family? That’s a different story. A decade after J.P. Blecksmith’s death on Veteran’s Day 2004, his family can tell you time doesn’t heal all wounds.

By Charlie PetersNot long ago, Ed Blecksmith found himself — physically and emotionally — in a sprawling cemetery, though not the one just past San Marino’s city limits where his youngest son and first wife rest.

On a French bluff overlooking hallowed Omaha Beach, Blecksmith stood among the graves of Allied soldiers killed during World War II’s invasion of Normandy. Weeks later, and without hesitation, the Vietnam War veteran and ex-Marine can tell you how many crosses and Stars of David are in the Normandy American Cemetery: 9,437.

Get the number right, Ed implores, because each soldier’s D-Day sacrifice should be counted individually. Each one of them matters to someone.

Scanning the 9,437 grave sites, Blecksmith thought, I know how each of your families felt.

In the 10 years that passed since his youngest child, J.P., was killed in action by a sniper in Fallujah, Iraq, Ed has tried everything to keep his son’s memory alive: granted interviews to documentary filmmakers and cable news networks, shepherded a foundation in J.P.’s name, and spoken with psychic mediums in an attempt to channel messages to his son.

But legacies are built on more than sharing messages; they’re strengthened on receiving them, too. When Ed placed a rose on the cemetery’s statue depicting a soldier ascending to heaven, the father wept for his son, and for those J.P. left behind when he died 10 years ago Tuesday — on Veterans Day.

To understand a decade of pain for Ed and others who loved J.P., you have to go back to where they lost him: on a dirty rooftop in the Al Anbar Province of Iraq in 2004. It’s where Marine Corps 2nd Lt. James P. Blecksmith stood before he fell, directing the India Company of the 3rd Battalion, 5th Marine Regiment, to clear the district’s buildings of insurgents.

The Flintridge Prep and Naval Academy graduate never saw the shooter who killed him. As a bullet entered his left shoulder and ricocheted through his heart, J.P. reportedly said, “I’m hit,” before falling to his knees. By the time help arrived moments later, one of San Marino’s favorite sons was gone at age 24. In the months and weeks leading up to J.P.’s death, his parents and two siblings admitted harboring dark beliefs that he would never come home. The sense of angst overwhelmed J.P.’s parents, Ed and Pam, and his older siblings, Christina and Alex. “When I’d drive home from work, I’d dread coming around the corner and seeing a [military] car parked there,” said Ed. On Nov. 11, 2004, following a Marine Corps dinner party, Ed breathed a sigh of relief when he found no strange car parked in front of his home.

But inside, Blecksmith found a teary-eyed Pam speaking with a Marine Corps captain and war officer. The military men delivering the tragic news had parked their vehicle a few houses up the street.

An estimated 2,000 mourners crowded into San Gabriel’s Church of Our Saviour and surrounding buildings for a hero’s funeral nine days later. By the end of a four-hour-long receiving line, wet makeup from grieving embracers caked the shoulder of Alex’s suit jacket.

In the days leading up to and following J.P.’s burial at San Gabriel Cemetery, the Blecksmiths hosted hundreds of San Marino well-wishers, who arrived with meals, beer and memories.

But when the visitations slowed, the Blecksmith family struggled to cope with a new sense of normalcy. In December, Ed and Pam were invited to San Francisco as the guests of honor for the Emerald Bowl college football game, featuring J.P.’s alma mater, the Naval Academy. Before the game, Pam said to Ed, “I don’t know if I can go on living without J.P.” Ed reassured her, but two months later, doctors diagnosed Pam with stage 4 colon cancer. Within three years, Pam was gone, too, and the family laid her to rest next to J.P.

Around his hometown, the name is unavoidable. Thanks to the J.P. Blecksmith Leadership Foundation, the soldier’s name is on a plaque in Lacy Park, a banner for the July 4 charitable 5K run, a Marine Corps building in Pasadena, a graduate program for veterans at USC and a scholarship at Flintridge Prep.

However, a legacy isn’t about what’s to come, but what’s been left behind for others. The memories of the manner in which J.P. lived — full-throttle, seeking adventure and honor — have changed his older brother and sister after his death.

Alex, 35, who grew up as the cautious and careful Blecksmith boy, hiked the Grand Canyon rim-to-rim last April and aims to scale Mexico’s tallest mountain in February. Christina McGovern, now a mother of three, began running long distances to have quiet time to think about — and talk to — J.P. The training culminated in an emotional Marine Corps Marathon in Washington, D.C., in 2005, where the only thing tougher than making it to the finish line was finding the finish line, as tears filled her eyes.

“When I run, I run for him, because he can’t anymore,” said Christina, who said she doesn’t mind if onlookers think she’s batty when she’s talking to J.P. as she runs alone. “Every time I wanted to quit, I knew he was there.”

Ed, now 71, won’t be climbing mountains or running marathons to honor a son who he said would have become a Marine Corps general or CEO of a big corporation. Instead, the father tried to learn from his own mistakes through the lesson of losing J.P.

In Vietnam in the fall of 1967, Ed lost 14 men in combat as a second lieutenant, and said he was callous in reporting the deaths to the soldiers’ families. “I had no idea what the families back home were going through,” said Ed, who has remarried and lives in Utah with his wife, Jane. “When J.P. was killed, I talked to two families of Marines I had lost and apologized for not making a greater effort to communicate back in the 1960s.”

When Ed needed more than memories — such as that of the young, military-minded J.P. dressing in his father’s fatigues and combat boots and digging a foxhole in an abandoned lot — he looked further for a connection to J.P. He found symmetry between J.P. and legendary Gen. George Patton: Both were San Marino natives who were baptized at Church of Our Saviour, and J.P. was killed on Patton’s birthday. More recently, Ed has reported feeling his son’s presence in his home on more than one occasion and sought out a psychic medium to communicate with him, which he said helps the grieving process.

“I don’t run around with a foil hat on my head, but the bottom line is that I miss him terribly. I don’t want to get mystical, but I think he’s my guardian angel now,” said Ed, who thinks of J.P. when he reads his favorite poem, A.E. Housman’s “To an Athlete Dying Young.” “He’s frozen in time. He’ll never get old. He’ll never fail.” Beyond the Blecksmiths, the memory of J.P. is perpetuated by his best friends. His senior photo is on Peter Twist’s refrigerator in Philadelphia, and Twist still owns letters the pals traded back and forth when the Blecksmith family moved to Seattle for five years in the late 1980s. J.P. died on Twist’s 24th birthday, and Twist said his annual birthday calls from old friends eventually turn into J.P. story swaps.

Those stories also get shared at a local annual Christmas party, according to friend Robert McKinley, who invites the Blecksmith clan to his family’s holiday party each year. Another high school buddy, Ross Fippinger, said J.P.’s tale has value for the next generation.

And, far from San Marino, in airports all over the nation, close friend and frequent traveler Alex Christian approaches uniformed military members to thank them and pray for them.

“I think deep down it made me feel like I was somehow talking to J.P. through all of them, which I know may sound silly to some, but in some ways it helped give me closure,” said the Dallas resident, a new father who lamented that his child wouldn’t know J.P.

The soldier’s sister, Christina, knows the feeling. She’s moving on — she doesn’t leave an extra place setting at the table for him like some might, she said — but Christina is still disheartened that her daughters won’t meet her hero.

“My brother is part of me, part of me they’ll never know, and I want my daughters to know that they had this amazing uncle,” said Christina. “When I think about how I want my girls to grow up, I want them to have his drive and passion for life, and to have the courage to stand up for what they believe in.

“For me, that is his legacy: something I feel like I need to teach my children.”

Standing 6 feet, 4 inches and weighing 230 pounds, J.P. owned the chiseled physique and a megawatt grin tailor-made for a casting agent looking for an American hero for a Hollywood film. He played the part, too: According to Ed, the former high school star quarterback selflessly switched to wide receiver at Navy without complaint, and never received a demerit in Annapolis.

Alex Blecksmith, who lives in Pasadena, said all the good things about J.P. have been crystalized in his mind. Unfortunately, the current state of Iraq is also clear to the Blecksmith family, which reopened their emotional wounds before they had healed.

Following J.P.’s death, the family always sought comfort knowing his sacrifice occurred during an initially successful — if divisive — military engagement in western Iraq. Any semblance of that justification is gone today.

When Islamic State of Iraq militants took back Fallujah, Christina began to wonder if her brother had died in vain, and Ed and Alex’s blood boiled during telephone calls with each other.

“It was a punch to the gut,” Alex said. “You see news reports that ISIS is marching all over Iraq … but when they take back the city where J.P. was killed, you think, ‘What was the point?’”

The retaking of Fallujah wouldn’t be the final time the family was confronted with heartache related to J.P.’s loss: In June, Flintridge Prep alum Scott Studenmund — who called J.P. his inspiration to join the armed forces — was killed in action in Afghanistan. Two months later, Ed sat with Studenmund’s mother, Jaynie, and tried to support her in the way people in San Marino had comforted him a decade ago.

Despite it all, the meaning of a military sacrifice like J.P.’s extends beyond the overseas operation. One example: a West Point grad is walking from Seattle to Baltimore for the Dec. 13 Army-Navy football game, dedicating each kilometer to a different fallen soldier. The final two kilometers will honor former Army quarterback Chase Prasnicki and Navy wide receiver J.P. Blecksmith.

More than 2,300 miles away from his hometown, the march into M&T Bank Stadium next month is yet another reminder of a man who won’t be forgotten.

Other Information

From The Los Angeles Times on October 4, 1998:

J. P. Blecksmith passed for three touchdowns, rushed for another and recovered a fumble for the Rebels in a nonleague game at San Dimas High.

Blecksmith, a senior quarterback, completed six of 17 passes for 167 yards and rushed for 63 yards.

Flintridge Prep. 6’ 3”, 200 lb. committed to Navy.

Photographs

Bronze Star

From JP Blecksmith Leadership Foundation; it's unclear if the award was actually made. (The website seems to have been last updated in 2009.)

Recommended Citation:

For heroic achievement in connection with combat operations against the enemy as 3d Platoon Commander, Company I, 3d Battalion, 5th Marines, Regimental Combat Team 1, 1st Marine Division in support of Operation IRAQI FREEDOM II from 28 September to 11 November 2004. During operations in Al Fallujah, Iraq, Second Lieutenant Blecksmith demonstrated tactical proficiency and natural leadership as he employed his platoon against a determined and criminal insurgent force. During defensive operations he coordinated tanks, artillery, air support and small arms against insurgent forces that enjoyed relative freedom of movement on all sides of his position. During one specific well-coordinated attack, he repelled insurgents without suffering casualties, despite the extremely close proximity of the fighting. During the assault on Al Fallujah, he seized Battalion Objective Three during the main effort attack, allowing the Regimental Combat Team to penetrate south. On 11 November, 3d Platoon came under fire while clearing in zone in the northeast corner of the Jolan District. As his platoon suffered two casualties, he orchestrated a medical evacuation under fire while employing his forces to reduce the threat. As he continued his attack south to clear in zone, again his platoon came under fire and without hesitating he charged atop a building to obtain a commanding view of the urban battlefield. Directing his squads from the front and exposed, he came under fire and was mortally wounded. By his zealous initiative, courageous actions and exceptional dedication to duty, Second Lieutenant Blecksmith reflected great credit upon himself and upheld the highest traditions of the Marine Corps and the United States Naval Service.

James is one of 2 members of the Class of 2003 on Virtual Memorial Hall.

The "category" links below lead to lists of related Honorees; use them to explore further the service and sacrifice of alumni in Memorial Hall.