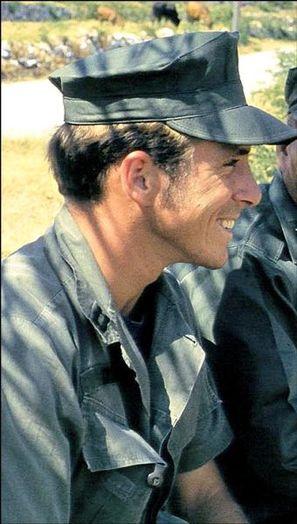

MELVIN S. DRY, LT, USN

Melvin Dry '68

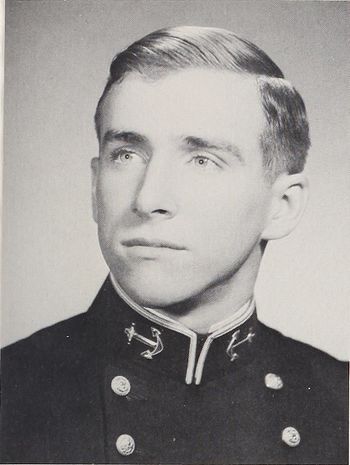

Lucky Bag

From the 1968 Lucky Bag:

MELVIN SPENCE DRY

Spence came to the Academy from nowhere in particular. He has done extensive traveling throughout the world as a Navy junior. Affectionately called "Hot Dogger" by those who know him, Spence can usually be found spit-polishing his vette, answering his feminine fan mail or sleeping. His glib tongue and good sense of humor have made him many friends. Due to a tragic birth defect (2 left feet) Spence was always a stand out in every P-rade. Spence has attained his objective of following in his father's footsteps here at the Academy. His high academic standing, warm personality, and unending energy made us all proud to serve under him when he was selected company commander. His unique qualities should make him a valuable addition to the surface Navy.

He was also a member of the 1968 Brigade Staff staff (3rd set) and the 8th Company staff (1st set).

MELVIN SPENCE DRY

Spence came to the Academy from nowhere in particular. He has done extensive traveling throughout the world as a Navy junior. Affectionately called "Hot Dogger" by those who know him, Spence can usually be found spit-polishing his vette, answering his feminine fan mail or sleeping. His glib tongue and good sense of humor have made him many friends. Due to a tragic birth defect (2 left feet) Spence was always a stand out in every P-rade. Spence has attained his objective of following in his father's footsteps here at the Academy. His high academic standing, warm personality, and unending energy made us all proud to serve under him when he was selected company commander. His unique qualities should make him a valuable addition to the surface Navy.

He was also a member of the 1968 Brigade Staff staff (3rd set) and the 8th Company staff (1st set).

Loss and Tribute

From the Washington Post, February 26, 2008:

Riding in the dark inside a Navy helicopter over rough waters off the coast of North Vietnam, Navy Lt. Spence Dry didn't hesitate when the time came to jump.

Dry, commanding a SEAL team, was determined to link up with the submarine USS Grayback in the waters below to continue a daring mission to rescue U.S. prisoners of war trying to escape from the Hanoi Hilton, the infamous North Vietnamese prison. " 'I've got to get back to Grayback,' " John Wilson, the helicopter crew chief, recalled Dry saying. "He was adamant that the mission go forward."

Finally, the helicopter crew spotted a flashing light they believed to be the submarine's beacon. Wilson slapped Dry on the shoulder, the signal to jump, and Dry disappeared into the night, followed by the three SEALs in his team.

But the helicopter was flying too high and too fast, and Dry, 26, died instantly upon impact with the water, the last SEAL to die in Vietnam. The circumstances of his death would remain tightly classified for more than three decades. Dry was given no recognition by the Navy, and his family received few answers. The Navy labeled it a training accident.

The U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis declined to add the 1968 graduate to its listing of alumni killed in action displayed in Memorial Hall, citing the accident classification. Yesterday, inside that ornate hall considered the heart of the academy, more than 200 friends and family members from the Washington area and abroad gathered for a ceremony in which Dry was posthumously awarded the Bronze Star medal with valor. His name was also formally added to the alumni scroll in Memorial Hall.

The guests included Wilson, the helicopter crew chief, as well as many of Dry's SEAL platoon members and the former commander of the USS Grayback. The Naval Academy's Class of 1968 showed up in force, including Adm. Michael Mullen, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Also paying his respects was retired Air Force Col. John Dramesi, one of the prisoners Dry was attempting to rescue.

Standing in the back of the hall were several dozen midshipmen who hope to become SEALs after graduation.

"Today has been a long time coming," said Rear Adm. Joseph D. Kernan, commander of the Naval Special Warfare Command, a speaker at the ceremony.

"It's sad that it's taken this long, but the upside is he's finally been recognized," said Wilson, who flew from Hawaii for the event.

Dry's younger brother Robert told the audience that the ceremony "fulfills my parents' fondest wish, that their firstborn son be recognized for his sacrifice. It's a fitting end to the tragic events that occurred 35 years ago."

Dry's father, retired Navy Capt. Melvin H. Dry, worked for a quarter-century to find out what had happened to his son and to get him recognition for his actions, but he died in 1997.

Dry's mother, Catherine "Kitty" Spence Dry, who lives at an assisted living facility in McLean, was too frail to attend the ceremony, said Robert Dry, a longtime Washingtonian now serving with the U.S. Embassy in Paris. "She's very proud," he said.

Classmates, fellow SEALs and others who served with Melvin Spence Dry recalled a charismatic man with an easy manner that won the affection of peers and subordinates.

"He was a guy you wanted to be around," Mullen recalled yesterday.

"He was a terrific young man, one of those people whose men follow him because they respect him, not because he told them to do it," said John Chamberlain, who was commander of the submarine during the 1972 mission.

Based on intelligence that prisoners had formed a plan to escape and travel by boat on the Red River to the Gulf of Tonkin, the Navy initiated a rescue mission, Operation Thunderhead.

On the night of June 3, Dry and three members of his SEAL Team One platoon were launched from the Grayback in a mini-submarine to establish an observation post on a small island near the mouth of the Red River.

But the mini-sub went off course, and the SEALs were forced to scuttle it. They were rescued by helicopter and taken to a guided-missile cruiser.

Dry and his team were flying back to the Grayback on June 5 to resume the mission, but the helicopter had trouble finding the sub and was flying too high and too fast when the SEALs jumped. Dry's neck was broken on impact; the other men were rescued treading water the next morning, one with serious injuries.

Wilson was the last man to see Dry alive, and it fell to him to pull his body out of the water. "I hoisted Spence out and laid him on the deck," he recalled.

Ironically, the planned escape from the Hanoi Hilton was called off because it was deemed too risky. "It was a devastating disappointment to us," Dramesi recalled yesterday. "It was tragic in all ways."

The effort to recognize Dry was spurred by a 2005 article in the U.S. Naval Institute's magazine, Proceedings, co-authored by retired Navy captains Michael G. Slattery and Gordon I. Peterson.

The authors scoured formerly classified materials to piece together details and contacted participants, including Chamberlain. "When I found out they'd originally classified it as a training accident, I was stunned," Chamberlain recalled yesterday. As the on-scene commander, he submitted the paperwork for the medal.

"He agreed that this oversight needed to be corrected," said Peterson, who works as military legislative assistant to Sen. James Webb (D-Va.).

Said Dramesi, "I've been looking forward to this day for a long, long time."

He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

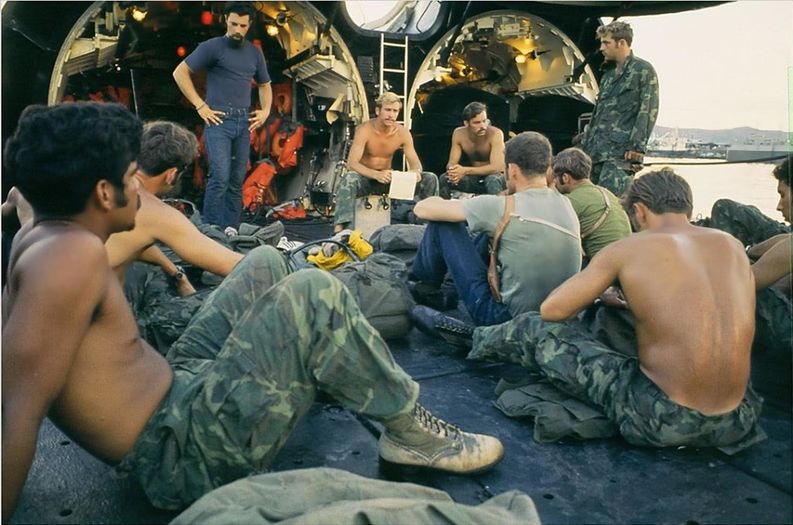

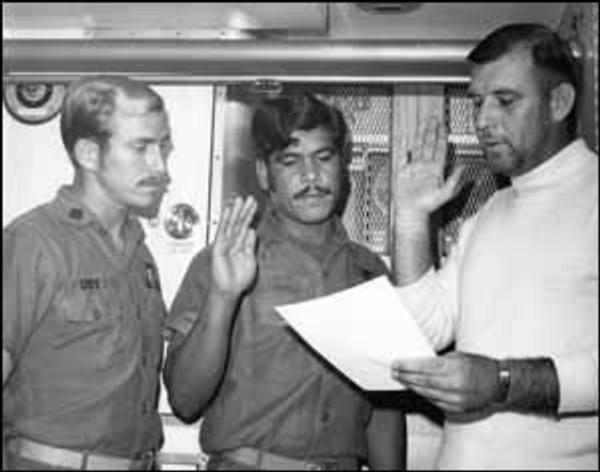

Photographs

Remembrances

From Wall of Faces:

Spence, good buddy at the USNA. Your friendship was appreciated by all of us. Nice and courageous officer, a real warrior. Always remember you!!! JOSÉ ANGEL CANO, 6/5/15

Spence and I were company classmates (1968) at the Naval Academy and became very good friends after 4 years together. Following graduation I bumped into Spence in June or July 1969 in Subic Bay. We both were stationed on Fletcher class destroyers. One afternoon we went jogging together around the base. As we ran we agreed that the "tin-can" Navy wasn't what either of us had expected and there had to be something else we could do that would be more fun and exciting. Then came that fateful moment: I suggested that we become SEALs. BINGO... Spence was immediately locked on and tracking... the rest is history... what a loss... by the testimonies of his team members Spence was obviously respected and liked by his men which is often times a unique combination. May Spence rest in peace... he has been missed now for over 35 years. DAVE MAULDIN USNA '68, THECOMMANDER@ILOVEDIXIE.COM, 3/24/07

Proud to serve with you -- Alpha Platoon

Words cannot express the feelings I have after all these years for all you have done for me and our country! Besides your family and friends, only the ones who knew you in those final weeks can possibly understand the USA's and our loss. You deserve the respect and acknowledgement for your sacrifice. Hopefully those with the vision to recognize you will do their duty to you and the country. I miss you for all these years. ROBERT HOOKE, BOB@HOOKEINC.COM, 2/14/07

SPENCE- THINK OF YOU OFTEN, ESPECIALLY AROUND THANKSGIVING- I'LL ALWAYS REMEMBER YOU IN YOUR NAVY DRESS UNIFORM FOR THE ARMY /NAVY GAME WHEN YOU AND YOUR MOM AND DAD CAME TO THE HOUSE- YOU WERE MY IDOL THEN- OUR HERO ALWAYS VIC (LARRY) HULTQUIST, TABANSHE@AOL.COM, 7/21/06

Teriyaki Shrimp “Spence – a Navy SEAL’s Story” (Old Working DRAFT)

Up the stone staircase from the rotunda at the center of the Naval Academy’s massive Bancroft Hall lies Memorial Hall. This hallowed place honors the memory of Academy graduates who gave their lives defending the Nation against its enemies. The standards and qualification criteria for this honor are demanding- as they should be. But one name nevertheless is missing from Memorial Hall’s honored dead – that of Melvin Spence Dry, class of 1968.

If the Navy was ever going to select a SEAL admiral from the class of ‘68, it would have been Spence Dry, hands down. At the Naval Academy he served as company commander of Eighth Company during the Fall of his senior year. He had a superior academic record, a great sense of humor, and was well liked by his classmates. He was smart, articulate, an aggressive operator and a natural leader. Spence had demonstrated those very traits throughout basic SEAL training and subsequent combat deployments to Vietnam with UDT-13 and SEAL Team One.

So as we stood at attention at “officer’s call” on a bright Coronado morning in SEAL Team One's compound during early June, 1972, the news that Lt Spence Dry had been killed during a “training accident” off the coast of Vietnam felt like a cold shot of winter surf.

We had heard from Spence in a letter not more than a few weeks before. In it he told us that he was finally getting to do some “really neat stuff.” Spence and I frequently competed to get assigned and deployed for any kind of “neat stuff,” and I envied his good fortune. Such opportunities were becoming rare as the Vietnam War appeared to wind down. Nixon’s Vietnamization program had ended all the routine SEAL platoon deployments. All that was left in Vietnam for us relatively new guys were one year tours as SEAL advisors and on exceptional occasions, a tailored mission deployment for a specific purpose or contingency. It was a deployment for a “special contingency” in Vietnam that Spence was leading when he was killed during a desperate attempt to accomplish an extremely difficult and hazardous mission.

Although Spence and I were classmates at the Naval Academy we really didn’t get to know each other well until the shared experience of surviving Basic Underwater Demolition/SEAL training (BUD/S). Training that included a cold winter Hell Week, seemingly endless formation runs in soft sand, and long cold ocean swims and small boat (IBS) rock portages at night through plunging surf during Pacific winter storms. Getting to know your future teammates well was a very big part of that experience. Starting in December ’69 we began as a winter class of 12 officers and over 100 enlisted. By graduation in June’70 we were down to a hard core of 5 officers & 22 enlisted. By then we all knew each others’ strengths and weaknesses as we knew our own. A particularly strong bond formed among those 5 surviving officers of BUD/S- class 56: Mike Cadden, Jerry Fletcher, Jim Hoover, Spence Dry, and me. That bond remains unbroken.

Following graduation from BUD/S four of us officers rented an old house on 4th street in Coronado, just up the road from the SEAL and Underwater Demolitions Teams. After long days of training and learning our craft at the “Teams,” we would often take our meals together at the Coronado Chart House, a favorite local restaurant during the Vietnam era. We would gather there on many occasions where Spence invariably ordered his favorite meal: teriyaki shrimp. Times were good then and all too short. We were young, well trained, and eager to test our mettle in combat.

Four of us were assigned to UDT-13 and within a few months we deployed to the Philippines with the entire command. Spence deployed almost immediately from there to Vietnam as OIC of Detachment Hotel near Da Nang. There he led his detachment on river reconnaissance, combat demolitions, and search & destroy operations along the Key Lam river. When Jim Hoover was seriously wounded at Dong Tam, Spence relieved him and I relieved Spence. Upon return from Vietnam Jerry, Spence, and I transferred to SEAL Team One.

The time at SEAL One was spent training hard, volunteering and competing for combat deployments, and making a general nuisance of ourselves at the local “watering holes” of San Diego. There SEALs and Naval Aviators would compete for attention during off duty hours and in between WESTPAC deployments. Our favorite haunts for these contests were The Down Winds, MCRD, “MexPac,” and The Miramar Officers Club of “Top Gun” fame. There some of us ended up banned for life. The memories of those uproarious and politically incorrect times are still vivid – especially, I’m sure, for Miramar’s former Command Duty Officer during one particularly regrettable encounter.

So it was a terrible shock to learn that Spence had been killed and as it started to sink in we wanted to know the specific details. Officially the word from on high was he had died in a “training accident,” the location and purpose of which were highly classified and disclosed only on a need to know basis. We needed to know more.

Gradually as the surviving members of his team returned to Coronado, we uncovered the bits & fragments that enabled us to piece together key parts of how the “training accident” occurred. Spence and his teammates had been forced to abort a highly classified clandestine reconnaissance and attempted rendezvous under extremely hazardous combat conditions. They had launched at midnight from a submerged submarine on 3-4 June 1972. After several hours of fighting too strong a tidal current, they had been compelled to scuttle their only mode of clandestine transportation, a SEAL Delivery Vehicle (SDV) whose battery power had ran out during their struggle against the current. Waiting all night in the enemy patrolled waters for daylight, they then executed an emergency Helo extraction and returned to the command ship – the USS Long Beach, for debrief. But they needed to return as soon as possible to the submarine. They had information vital for a back-up team preparing to launch a second attempt, and Spence was determined to see that they got it.

That night the SEALs attempted a midnight link-up with the submarine somewhere off the coast of North Vietnam. They were riding a Helo that was trying to locate this submarine operating under strict radio silence during limited visibility on a very dark night. Their attempted rendezvous was further complicated by the highly classified nature of their mission, an operation so secret that the submarine had to remain submerged and undetected even by the US Navy’s own Fleet on the water’s surface. Its ships patrolled throughout this area of the Tonkin Gulf and were unaware of any friendly submarines or swimmers operating in their midst. According to one participant, a Navy destroyer had already fired on the submarine– the USS Grayback, earlier during snorkeling operations. Fortunately it had missed.

When the Helo pilot thought he had finally spotted the signal light from Grayback, Spence and his men prepared to conduct a Helo cast to link-up and lock-in to the sub. When told they were over their objective after several unacceptable passes, including one over the North Vietnam coast, Spence stepped out of the Helo and the rest of the SEALs rapidly followed. The Helo was too high and fast for safe entry and the jumpers hit the water hard. Spence was killed and the others injured - two seriously. There was no submarine in the immediate vicinity to link up with so they treaded water until daylight when they were spotted and picked up. During the course of the night they found Spence’s body and held it for recovery.

We all knew that given similar circumstances every one of us would have jumped once told the sub had been located and it was time to “drop.” We learned years later what the “really neat stuff” was that Spence was alluding to in his letter. Many of the details were later described by Moki Martin in his on scene account of Operation Thunderhead and published in Orr Kelly’s Never Fight Fair. Other participants also revealed additional details. Spence and his team had deployed in an attempt to rescue American POWs who were planning to escape from a North Vietnam prison. He had died during the course of that attempt.

Spence would be the last SEAL to die in Vietnam. The Navy and another government agency involved had decided that his death was “accidental.” It was not specifically caused by enemy fire, and therefore, according to the cover story, simply a tragic mishap. Besides, disclosing the highly classified nature of the operation that surrounded the circumstances of his death at the time would put future rescue attempts at risk.

But the risk to Spence and his fellow SEALs on that particularly dangerous operation was from more than just the looming threat of hostile fire. Several potentially treacherous operational hazards were also closely and inherently linked throughout the entire operation’s full mission profile. And although certain aspects of his mission still remain classified, these risks most certainly included: the night underwater lock out and launch from Grayback, the long hours of submerged transit through enemy waters to the target area in an unproven free flooding Mark VII Mod 6 SDV, the strong tidal current that made mission success impossible and forced the team to abort, and the high risk of detection and engagement by aggressive enemy patrol boats that probed the coastal waters of the Tonkin Gulf during the several hours that the SEALs where forced to surface and await emergency recovery by Helo. To these mission components that “went with the territory” must be added the one that killed him. In a desperate attempt to return to Grayback and brief the back-up SDV team about the strong tidal current prior to their launch of a second rescue attempt, Spence had leaped into the night from a Helo too high and fast in an attempt to link-up and lock-in to a submarine that wasn’t there.

Throughout the entire rescue attempt his team needed to remain undetected - even by friendly forces. But if the enemy did detect the SEALs and forced them to return fire, it would have been merely one more challenge to overcome in a long and continuous sequence of high risk mission profile events.

We didn’t know those details back then. All we knew was that a close friend and good teammate, an outstanding officer with tremendous potential, had been killed. So on the night that we learned of his death four of us gathered once more at the Chart House and asked for a table for five by the window. It was a nice spot – one that Spence surely would have approved of – overlooking Glorietta Bay and the lights of the Coronado Bridge. We each retold stories about Spence and raised our glasses to the separate place that we had made the waiter set - with teriyaki shrimp. MIKE SLATTERY, 12/16/05

To my "Segundo" at the U. S. Naval Academy, 1966

There's not much I know about Spence's Vietnam service. I know he was a SEAL, and that he was lost off the coast of Vietnam in 1972. I had originally heard that he had been shot while on a mission, but that later proved to be incorrect.

My memories of Spence were not always fond; to understand that, you have to understand that a Naval Academy Fourth-class (freshman) Midshipman's "Plebe Year" is not something that one looks back on with fondness; or at least, it wasn't in 1966, the year I was a Plebe: a member of the class of 1970.

Spence was my "Segundo"; each Plebe was assigned a Second-classman (junior) to correct their copious misbehaviors on the road to becoming a Naval Officer. Spence's room was next door to mine and my roommate's, as we were assigned to the Eighth Company, Second Battalion, Brigade of Midshipmen, Annapolis, Maryland, 21402.

Spence was, as the saying goes, tough but fair. Of course, at the time, I would never have called him "Spence"; it was "Mr. Dry", at least until he "spooned" me (shook my hand, thereby removing the "rates" between us) late in my Plebe year. Spence's nickname was "Bananaman" (I never learned why); his roommate was a guy named Terry Vial ("Veal Cutlet"), who was an Aero major (as was I), since both Terry and I wanted to fly. But Spence always wanted to be a SEAL.

Spence was a good-looking, athletic guy. He had a 'California' air about him, even though he was from upstate New York (I was from Southern California), and he was a decent and honorable man -- unlike some of the other upperclassmen of the time.

You can imagine that the power upperclassmen had over Plebes (which stopped just short of actual abuse) sometimes led to excesses; it was like a year-long rush of a fraternity, with the difference being that if you washed out of the rush, you weren't just out of the fraternity, you were out of the school.

In any case, Plebe year was tough, and Spence could have made it a lot tougher, but he didn't. He really seemed as though he wanted me to be better in all things -- I hope I didn't let him down.

I recall one time when I grabbed his hand in a 'pseudo-spoon'. The setting of this humorous story is at 'evening come-around', which takes a little explaining. Whenever you were caught in an infraction, no matter how small, you were given a 'come-around'; you had to report to an upperclassman's room during one of the two come-around periods each day: the half hour before morning meal formation and the half-hour (or so) before evening meal formation. General 'come-arounds' meant you reported to your Segundo's room.

One time at 'evening come-around', Spence was putting me through some kind of calisthenics as punishment for some infraction (generally, you always had more come-arounds than you could work off in two lifetimes, so you just always showed up for them). I had probably taken my eyes "out of the boat" (looked to the side instead of straight ahead), or had a speck of lint on my Service Dress Blues.

In any case, he was 'running' me at come-around, and, while making some kind of a point as to how screwed up I was, he made the mistake of putting his hand out the way you would if you were offering to shake hands with someone. Seizing the moment, I grabbed his hand, shook it, and said, "Thanks, Mel!" (Spence's first name was 'Melvin', although he didn't use it). He smiled, and said, "Mel, huh?", and then proceeded to run my butt into the ground. I hadn't thought it would work, but I had to give it a try!

I lost touch with Spence after he graduated, although I did hear that he had gone to SEAL training. His roommate, Terry Vial, was killed in 1969 during a flight training accident. I have heard that it was during his first carrier qualifications, but I never was able to confirm that.

I was almost through flight training when a Naval Academy classmate of mine, who also had known Spence, told me that he had been killed in action in Vietnam. My biggest feeling was of disbelief -- he seemed like one of those guys who had the world by a string, and who would come through any situation unscathed. I already knew, but had it reinforced, that the Vietnam War had no similarity to Hollywood's interpretation. The strong, decent, competent guys got killed, too. The heroes didn't always make it out alive.

As far as it went for me, I just missed the war. I joined my Navy Fighter Squadron, VF-74, while it was on 'basket leave' from the last Vietnam cruise on the USS America. The war had just ended; VF-74, along with VMFA-333, were the last Navy and carrier-based Marine squadrons in the war, and I joined them two weeks after they got back. I don't regret missing the war at all; I just wish it had never started.

My last story concerning Spence happened during a visit to the Naval Academy after I had left the Navy. I live on the west coast, and very rarely get back to the east coast, but I was taking my wife on her first trip back east and decided to show her the Naval Academy.

You have to understand that to many of us who went there, it was the ugliest place in the world, especially in the winter. Granite buildings, cold aspects, not a place to bring someone you are trying to impress. Well, we happened to hit our visit to "Boat School" during 'Commissioning Week' in late May, which is what we used to call "June Week".

The Academy looked like something out of Hollywood. The day was beautiful and clear; there were boats sailing on the Chesapeake and the Severn river. A gentle breeze blew off the bay. The grounds were perfect, the grass almost glowing green and perfectly cut, and the Academy looked like a movie set. The Blue Angels did an air show; everything was perfect and beautiful. My wife, who had heard story after story of how horrible the Academy was, thought I must have been insane not to love this beautiful 'campus'! If only she knew the truth . . .

As we were walking into the Rotunda of Bancroft Hall, the dormitory that houses the Brigade of Midshipmen, I saw an easel off to one side. It was titled something like, "To those who have gone before us", and was a list of the USNA graduates who had been killed in Vietnam.

I went up to the list, searching for Spence's name. It wasn't there! I thought, for just a moment, that maybe my classmate had got it wrong, and that Spence was still alive! I couldn't believe it; it felt so good to think of him as still with us. After a few moments, reality set in. I knew he was gone. Later that day, touring the Academy graveyard, I came upon another such list; his name wasn't on that one, either.

At the end of that week, we went to the Wall in D.C., and I looked up his name. There it was: Panel 1W, Row 38. Melvin Spence Dry. I knew he was really dead; only those of us who know someone on that Wall can understand how I felt at that moment.

I e-mailed the Academy, and told them of the omission of Spence's name on the lists. I never heard back from them. But those of us who know him, know of his sacrifice for us; and of all those many sacrifices. All of those brave people, gone.

But not forgotten. I miss you, Spence. I wish I had known you better. I know this is a poor memorial, but I just wanted everyone to know that you are not forgotten BRUCE HARRISON, 2/12/01

Extended Obituary

From Proceedings of the Naval Institute, July 2005, by Captain Michael G. Slattery, U.S. Navy (Retired) and Captain Gordon I. Peterson, U.S. Navy (Retired):

Early in 1972, two U.S. airmen being held as prisoners of war at the infamous "Hanoi Hilton" prison set in motion an escape plan. In response, the U.S. Pacific Fleet orchestrated what became known as "Operation Thunderhead," a rescue mission that played out that June in the Red River delta.

Special operations forces from SEAL (sea, air, land) Team One and Underwater Demolition Team (UDT)-11 were assigned to assist the POWs. One of them, Lieutenant Melvin Spence Dry, U.S. Navy, was killed on the classified mission — the last SEAL lost during the Vietnam War. His father, retired Navy Captain Melvin H. Dry, a 1934 Naval Academy graduate and a submariner, spent the rest of his life trying to learn the circumstances surrounding his son's death. The details, however, were long shrouded in secrecy.

Following his Naval Academy graduation in 1968, Spence Dry reported to postgraduate school. Sea duty followed on the destroyer USS Renshaw (DD-499) but he wanted to join the special-warfare community. Late in 1969 he reported to the 20-week Basic UDT/SEAL Training course of instruction at Naval Amphibious Base, Coronado, California.

Class 56 initially numbered 12 officers and more than 100 enlisted men, including an Academy classmate, Lieutenant (j.g.) Michael G. Slattery. At graduation in June 1970, the class numbered five officers and 22 enlisted. The officers — Mike Cadden, Spence Dry, Jerry Fletcher, Jim Hoover, and Mike Slattery — formed a particularly close bond. Four of the officers, including Dry, were assigned to UDT-13 and deployed within a few months to the Republic of the Philippines. Dry soon moved on to the Republic of Vietnam, where he served for three months as officer-in-charge of the team's Detachment Hotel, based near Danang. There he led his detachment on river reconnaissance, combat demolition, and search-and-destroy operations along Vietnam's Ky Lam River.

Upon their return from Vietnam in 1971, Slattery, Fletcher, and Dry were assigned to SEAL Team One. The team's primary mission was to engage in unconventional warfare, conducting counterguerrilla and clandestine operations in coastal and riverine areas, but with President Richard Nixon's "Vietnamization" policy in full swing, the only combat assignments were one-year tours as advisors to South Vietnamese units.

In November 1971, however, Dry was given the chance to form his own contingency platoon and prepare it for a six-month deployment to the Western Pacific. Lieutenant Robert J. Conger Jr., Dry's assistant officer-in-charge at the time, recalled that he and Dry spent two weeks screening more than 80 enlisted volunteers to identify the 12 best qualified for SEAL Team One's "Alpha" platoon.

"Spence was sure of his direction, and the positive, yet attainable, goals he set for himself gave the platoon a unity and esprit seldom found in any organization," Conger said. One of the more experienced combat veterans in the platoon described Dry as one of the best officers that Team One ever had. Chief Petty Officer (soon to be Warrant Officer First Class) Philip L. "Moki" Martin, a highly experienced SEAL who had served multiple combat tours in Vietnam, rounded out the platoon's leadership. He considered Dry an "operator" — just about the highest accolade a SEAL can give. The 11 other enlisted men also reflected a wealth of combat experience.

Alpha platoon deployed to Okinawa for additional training and stood by.

Operation Thunderhead

Armed with fresh intelligence that the prisoners were planning to steal a boat and travel down the Red River to the Gulf of Tonkin, Admiral Thomas H. Moorer, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, on 15 May 1972 authorized the U.S. Pacific Command to execute Operation Thunderhead, a rescue plan proposed by the Pacific Fleet a month earlier. Full details of the operation were known to only a handful of officers individually cleared by Admiral John S. McCain Jr., the PACOM commander.

Dry's platoon left Subic Bay in April in the amphibious-transport submarine USS Grayback (LPSS-574), skippered by Commander John D. Chamberlain. The Grayback , formerly a Regulus guided-missile submarine, had been converted in 1968 to support clandestine operations. The diesel-electric submarine was modified to carry approximately 60 troops plus four SEAL delivery vehicles (SDVs) in two "wet" hangars on her bow. The SDVs were small, free-flooding, unpressurized fiberglass minisubmarines equipped with rudimentary navigational equipment.

The rescue plan was straightforward, but challenging. Dry and Martin would launch at night from the submerged submarine in an SDV piloted by two UDT-11 operators already embarked in Grayback and head for a small island off the mouth of the Red River. There the two SEALs would establish an observation post and watch for any sign of the escapees. "The time Spence and I were to spend on the island was a minimum of 24 hours and up to 48 hours," Martin remembered. "We were to look for a red light on a boat during the night and a red flag during the day."

Should the escaping POWs be sighted, the two would intercept them and coordinate their rescue with the waiting ships of the Seventh Fleet. North Vietnamese soldiers garrisoned the island. Occasional Vietnamese fishing boats plied the waters, and enemy patrol boats were always a possibility. There were other concerns, including a night underwater lock-out and launch from the Grayback in an under-powered SDV; a cold, submerged transit to the island in the confined and totally dark hold of the unproved free-flooding Mark VII vehicle; strong currents and tidal conditions; and the need for precise underwater navigation (in the days before the Global Positioning System).

Seventh Fleet helicopters conducted over-water night surveillance along North Vietnam's coast as the date for the escape approached. The Grayback arrived on station on 3 June 1972. Chamberlain and Dry decided to conduct a clandestine SDV reconnaissance mission that night. After dark, Chamberlain launched the vehicle at the end of flood tide to provide a maximum amount of slack water; he planned to recover it on the ebb tide. "Operation of a four-knot SDV in a two-knot current was extremely challenging," Chamberlain recalled, "and required not only excellent driving skills but also a fine understanding of navigation."

Dry, Martin, and the two UDT operators, Lieutenant (j.g.) John Lutz and Fireman Thomas Edwards, launched from the submerged Grayback shortly after midnight, but a combination of navigational errors and the strong current took them off course. After searching for more than an hour without sighting the island, the crew was compelled to abort the mission and, unable to locate the Grayback , scuttle their underpowered SDV after its battery power was exhausted. They planned to head out to sea if they could not locate the submarine.

The men were treading water a few miles off the coast when rescued early the next morning by a combat search-and-rescue HH-3A helicopter assigned to Helicopter Combat Support Squadron (HC)-7. To preserve operational security, Lutz used the helicopter's door gun to sink the SDV, which was too heavy to be retrieved. The four men were flown to the nuclear-powered guided-missile cruiser USS Long Beach (CGN-9), the command ship for Thunderhead, where they debriefed, communicated briefly with the Grayback, and planned their next steps.

"We've Got to Get Back to Grayback"

Dry, aware of the impending launch of the second SDV, knew that he and his men had to return to the Grayback quickly. The Navy was prepared to let the mission run up to three weeks, if necessary; given Dry's key leadership role and Martin's combat experience, both were needed if a follow-on SEAL insertion using another SDV was to succeed.

The decision was made to transport them by helicopter from the Long Beach for a night water drop (a "cast" in SEAL/UDT parlance) next to the Grayback at 11 p.m. on 5 June. The plan called for the helicopter's crew to make visual contact with the Grayback 's infrared (IR) signaling light atop the submarine's snorkel mast, which operated in beacon mode during Operation Thunderhead. In this configuration, it was a revolving, flashing red light. During briefings with the pilots, Dry and Martin emphasized that the maximum limits for the drop were "20/20" — 20 feet of altitude at an airspeed of 20 knots, or an equivalent combination.

The weather was overcast, with sea state 1-2, indicating a maximum wave height of approximately four feet. HC-7's "Big Mother" crew was faced with finding the Grayback while maintaining radio silence in cloudy weather on a dark night. Martin noted high winds and two- to three-foot swells as he boarded the helicopter on the Long Beach.

Problems began soon after the helicopter arrived near the Grayback's expected position. Multiple passes failed to reveal the submarine. To complicate matters, Dry could not communicate directly with the helicopter's pilot. Only the crew chief, Petty Officer First Class John L. Wilson, and Lieutenant Commander Edwin L. Towers, a Seventh Fleet staff officer temporarily assigned to the operation, were linked through the helicopter's internal communications from the cabin to the pilots in the cockpit.

As the aircrew desperately searched for the Grayback's beacon, Dry and his men prepared to enter the water and lock-in to the submerged submarine. Several approaches were aborted when it proved impossible to confirm the submarine's presence. At one point the helicopter inadvertently passed over the surf line and flew over North Vietnam when the crew mistook lights from a dwelling for the submarine. "It was a very hair-raising night," Wilson remembered.

During another difficult approach to the intermittent light just prior to the helicopter's last pass, the pilot overshot, flared the helicopter to dissipate airspeed as he transitioned to a hover, and then backed down toward the light. He descended within ten feet of the surface in a tail-down attitude. Water splashed into the cabin and almost swamped the helicopter before the pilot, warned by his crew chief, waved off for another try.

In near-desperation Wilson passed his helmet (with its lip microphone) to Dry so he could talk directly to the pilot about his concerns with the helicopter's altitude and speed. Dry and Martin had ample reason to worry.

According to a post-mission assessment, Dry informed the helicopter crew that they were too high, too fast, and downwind. Specifically, they were approaching the drop point with the winds, estimated at 15 to 20 knots, on the helicopter's tail. The velocity of the tail wind, added to the helicopter's forward speed, was well beyond the 20-knot ground speed needed for a safe jump. "They wanted us out, and we felt the altitude was too high and the speed too fast," recalled Martin, an experienced parachute jumpmaster. "As drop-master, I was looking for the tell-tale signs of spray from the helo — either coming in the door or when I looked toward the rear and below the helo."

Mindful of the helicopter's fuel state, Dry told Martin that time was running out — they needed to return to the submarine. "I remember seeing Spence's face in the dim red helo light," Martin said. "His last words to me were, 'We've got to get back to Grayback.'"

Finally, the helicopter crew observed a flashing light and assumed they had sighted the submarine's beacon. The pilot, not trusting the helicopter's automatic stabilization equipment, made a manual approach and, as he neared a hover, called, "Drop, drop, drop." "It was dark and windy," Martin said, "but I could see the helo's sea spray, especially on the dark sea surface."

Wilson, a veteran combat search-and-rescue diver with 29 career rescues to his credit when he retired as a chief petty officer, slapped Dry on the shoulder — the signal to jump. The final decision rested with Dry, but there was no hesitation. He dropped from the helicopter into the darkness, followed in quick succession by his three team members as the helicopter began to gain altitude and airspeed. "I knew right away that we were too high and too fast," Wilson related, "but it was too late."

"I was third in the drop," Martin said. "I exited and counted — one thousand, two thousand, three thousand . . . followed by 'God dammit,' and then I hit the water. I believe by my count that I was over 50 feet, possibly even 60 feet." Again, according to Martin, the cast was conducted downwind, adding another 15 to 20 knots of forward velocity when the jumpers hit the water.

The chief of naval operations told Captain Dry that his son had exited the helicopter at about 35 feet, but the survivors have no doubt that the helicopter was much higher. "A combination of too much speed and altitude [did] not allow any jumper to get a proper body position to enter the water. All four of us were injured," Martin related.

Dry died immediately of "severe trauma to the neck" caused by impact with the water, according to the Navy's death report. Two other team members were badly shaken, and one was seriously injured. Martin and Lutz answered one another's call, but there was no reply from their other teammates. Martin set out to find them. Edwards had broken a rib and was semi-conscious when Martin found him and inflated his life vest. Visibility in the water was later estimated at 10 feet, but the SEALs said it was closer to zero in the muddy water off the enemy's coast.

There was no response to their calls for Dry, although they estimated they were only 15 to 20 yards apart on their cast.

Worse, the flashing lights detected by the helicopter crew were not on the Grayback; in fact, they were the emergency flares and strobe lights used by the crew of the second SDV to alert the incoming helicopter to their own predicament.

Unknown to the pilots and the SEALs on Dry's helicopter before their drop, the Grayback had launched its second vehicle several hours earlier for abbreviated requalification launch-and-recovery operations. According to Chamberlain, the vehicle was to remain within acoustic homing beacon range of the submarine so that it could return as desired. Upon launch, however, it foundered in approximately 60 feet of water. Eventually, its crew of four abandoned it when their air ran out; subsequently, they made an emergency free ascent to the surface.

Chamberlain, with radar contacts indicating North Vietnamese patrol boats, had radioed to abort the night drop, but his message arrived too late.

Martin, Lutz, and Edwards saw a strobe light, heard voices, and swam to the second SDV's team. The group drifted with the seas. About 1 a.m., they found Dry's lifeless body, inflated his life vest, and held him and Edwards in tow as they swam seaward to be rescued.

The North Vietnamese patrol boats in the area did not detect them, and an HC-7 helicopter alerted by Chamberlain rescued the men at dawn and returned them to the Long Beach. Dry's body and the seriously injured Edwards were then flown to the carrier USS Kitty Hawk (CV-63).

The Grayback remained on station in the shallow waters for an additional two days — relying on periscope sightings to detect any escaping POWs — before Chamberlain was ordered to a safer patrol area. The remaining six members of the mission later were transferred from the Long Beach to the submarine on 12 June. With the likelihood of a successful prisoner escape by sea lessened by the recent U.S. mining of North Vietnam's ports and rivers, Operation Thunderhead was soon terminated.

A Father's Quest

Dry was the last SEAL killed during the Vietnam War. As it turned out, the leadership at the Hanoi Hilton had called off the escape attempt over concern for the plan's risk and fear of retribution. Unfortunately, there was no way of quickly informing anyone outside the prison walls about this decision. Those assigned to detect and recover the fleeing Americans continued to dedicate themselves to their rescue.

In Scotland, Dry's parents were notified on 12 June of their son's death in a "training operation," the government's cover story for the secret mission. Captain Dry's diary entry the following day consisted of one word: "Desolation." His son's remains were returned to the United States, and he was buried at Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors on 22 June. Admiral Bernard Clarey, the U.S. Pacific Fleet commander, met with Captain Dry in the Pentagon and explained the mission in a general way.

The operation's cover story did not ring true as news of the mission slowly filtered back to Coronado. Like the men of SEAL Team One, Captain Dry also was dissatisfied with the Navy's explanation. Over the next 25 years he sought, in vain, to induce the Navy and the Naval Academy to recognize his son's sacrifice.

The Navy did not share the findings of its 1972 joint investigation. "In nearly five years I've been given no information about exactly what happened at the scene of the accident," he wrote five years later. Finally, the Grayback's commanding officer, in a personal letter to Dry in 1981, provided a fuller accounting of his son's death. Others in the Navy who served with his son also filled in additional details through the years.

With the exception of an "end-of-tour" Navy Commendation Medal awarded to Lieutenant Conger, it appears that no member of Dry's team was decorated or otherwise recognized for their actions during the daring rescue mission — not even Warrant Officer First Class Martin, who saved the life of the seriously injured member of his team and rallied the remaining survivors until their rescue. Captain Dry's attempts to have his son awarded a posthumous Purple Heart were denied by the Department of the Navy, which maintained his loss was not the result of enemy action.

Similar requests to the Naval Academy during the 1990s to recognize the younger Dry's combat death also were unsuccessful, despite interest by former Secretary of the Navy James H. Webb Jr., one of Dry's Academy classmates. "The naval service is rightly stringent in awarding the Purple Heart and in assigning the status of killed in action," Webb wrote in the Naval Academy's Alumni Association's magazine in 1999. "But in the complicated world in which we have lived since the end of World War II, many who perished during operational missions, directly related to national defense, paid a price that was clearly measurable in the Cold War's victory."

The Naval Academy did not include Spence Dry's name on a listing of its alumni killed in action displayed in Memorial Hall owing to the Navy's initial determination of his death as an operational accident. "In order to be listed on that memorial," the Academy's Alumni Association said, "the Secretary of the Navy must have designated the individual KIA [killed in action] on the casualty report. Lt. Dry was not noted in this category."

Dry's leadership and dedication remain unrecognized by the Navy, although those most familiar with his loss have no doubts regarding his leadership and heroism that night. Ten days after the fateful night cast, all 13 surviving men of the platoon signed a joint letter to Captain Dry honoring their fallen commander. They wrote that ". . . His memory will remain with us so long as man values positive leadership and courage in the face of danger."

Captain Dry died in 1997. By then, he knew most of the details surrounding his son's death, but his quest to have the Navy honor his son's wartime sacrifice went unfulfilled. Father and son are buried in a common grave in Arlington National Cemetery. Captain Dry's dolphins are engraved on the top of the tombstone's face; his son's SEAL insignia is engraved at the bottom.

There are extensive author's notes at the original site as well.

Note: Despite the article's assertion above, Spence is listed as on the killed in action panel in the front of Memorial Hall.

Related Articles

Terry Vial '68 was also in 8th Company.

The "category" links below lead to lists of related Honorees; use them to explore further the service and sacrifice of alumni in Memorial Hall.