HENRY N. PILGER, 1LT, USMC

Henry Pilger '70

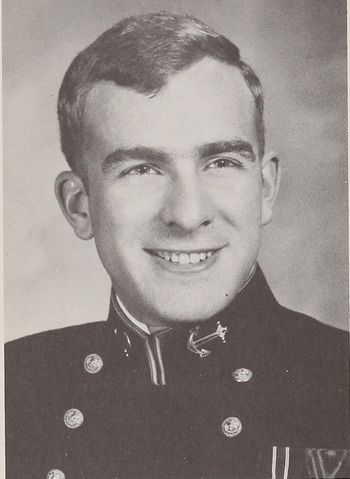

Lucky Bag

From the 1970 Lucky Bag:

HENRY NICHOLAS PILGER

North Syracuse, New York

"Captain Easy" came to the infamous trade school after an illustrious academic and athletic career in North Syracuse, New York. He quickly adjusted to the new routine and began making successful assaults on the Academic Departments and athletic fields. The latter occasionally resulted in short sabbaticals for recuperation. But, he made the best of a poor situation by calling in support from his little black book. "Pilge" constantly expanded his activities and could be found studying the TV Guide or doing research in many D. C. establishments. Mathematics was Rick's forte, and he spent much time giving E. I. to his puzzled friends. His decision for Marine green with wings surprised no one, and he will be a welcome addition to any command.

He was also a member of the 12th Company staff (fall).

HENRY NICHOLAS PILGER

North Syracuse, New York

"Captain Easy" came to the infamous trade school after an illustrious academic and athletic career in North Syracuse, New York. He quickly adjusted to the new routine and began making successful assaults on the Academic Departments and athletic fields. The latter occasionally resulted in short sabbaticals for recuperation. But, he made the best of a poor situation by calling in support from his little black book. "Pilge" constantly expanded his activities and could be found studying the TV Guide or doing research in many D. C. establishments. Mathematics was Rick's forte, and he spent much time giving E. I. to his puzzled friends. His decision for Marine green with wings surprised no one, and he will be a welcome addition to any command.

He was also a member of the 12th Company staff (fall).

Loss

Henry was lost on September 23, 1972 when the helicopter he was co-piloting crashed in Norway during a NATO exercise.

Other Information

From Class of 1970 40th Reunion Book:

Born in San Diego, “Rick” Pilger came to Annapolis after an illustrious athletic and academic career in North Syracuse, NY and quickly established himself as one of the best-liked guys in the Company. Tough both physically and mentally, he was a standout in math and in all sports, especially soccer. He was a truly gifted leader and was Company Commander First Class Year, an honor he truly deserved. Rick was always upbeat, exuding “perpetual cheerfulness” in the words of one classmate, and had a great sense of humor with a distinctive laugh and voice that had a bit of a Great Lakes twang. One classmate remembers visiting Rick in the hospital after he’d broken his jaw playing soccer and seeing Rick with his jaw wired shut playing chess with another Mid who also had his jaw wired shut, the two of them arguing over something and waving scissors, each threatening to cut the other guy’s wires. Even the nurses laughed at the absurdity of it. Rick was the kind of guy everybody liked being around, with an easy going charisma that made you want to follow him. He had a beautiful powder blue TR-6 First Class Year and, inspired by Major Kostesky, went Marine Air, receiving his wings in April of 1972. He married Debbie Wadsworth in June 1970 and they had a daughter, Abigail.

1st Lieutenant Henry N. “Rick” Pilger tragically died in the service of his country of injuries from a helicopter crash during a NATO exercise on Grytoga Island, Troms County, Norway, on September 23, 1972, while attached to Heavy Helicopter Squadron 461, Det. “S.” He was the co-pilot.

Rick’s death was a shock to his classmates and a reminder of the high cost of freedom. While his star shone brightly for too short a time, all who knew him know that had he been granted a full life there was no upper limit to what his accomplishments might have been. He is greatly missed.

Henry was survived by his wife, "he leaves his parents, Mr. and Mrs. Bernard Pilger of North Syracuse N.Y.; a daughter Abagail Pilger at home; three brothers, Bernard Pilger with the Navy in Hawaii, Gregory Pilger and Dennis Pilger, both of Syracuse, N.Y.; and a sister, Marie E. Pilger, also of Syracuse, N.Y." He is buried in the Riverside Cemetery of Farmington, Connecticut.

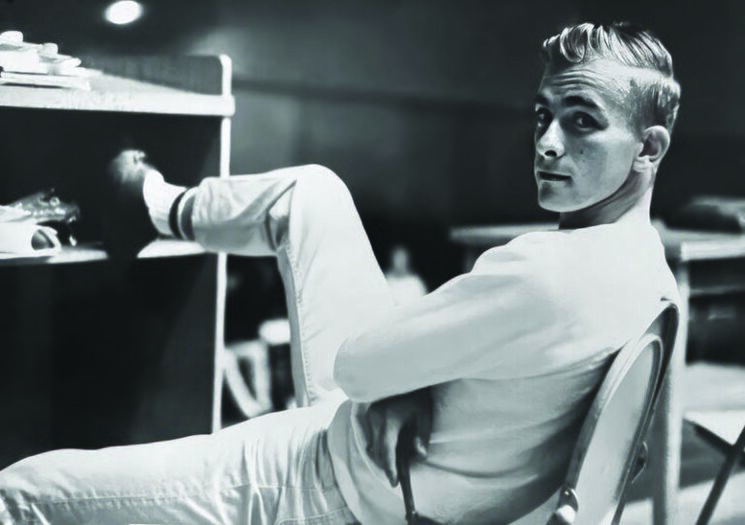

Photographs

From The San Diego Union Tribune on November 11, 2021:

This story starts with a doctor from northern Norway hunting grouse on the remote island of Grytøya off the coast.

Hans Krogstad happened to look down and couldn’t believe what he saw wedged between two rocks by his feet, something very out of place in that desolate landscape.

It was a gold ring bearing a blue star sapphire. He pried it out and studied it. It bore the insignia of the U.S. Naval Academy, Class of 1970. Engraved inside was the name: “Henry N. Pilger.”

Krogstad’s accidental discovery in 1993 and his desire to return the ring to the Pilger family launched him on a long path of twists and turns, dead ends and strange coincidences.

This year, 28 years later, it led him to a woman named Abigail “Abby” Boretto, who lives in Poway.

But I digress. As they say of life, it is not the destination but the journey that is the true adventure.

On that fateful day, Krogstad also had found some fragments of metal and a green military glove with missing fingers. From island locals, he learned of the fatal crash of a U.S. Marine helicopter on the stony mountain 21 years earlier.

Krogstad told his story to Simen Loholt, a friend of his son. Loholt is a reporter for iHarstad, an online publication covering the city of Harstad, with 27,000 inhabitants in northern Norway.

Loholt wrote about the discovery and shared the story with me.

I recently contacted Krogstad, who told me: “My first thought was that this ring must be returned to the family because maybe the pilot had a wife or children who might like to have the ring back.”

But that was not easy. He learned that the U.S. military, not Norwegian authorities, had investigated and removed the crash debris. So, he contacted a friend working at the American embassy in Stockholm, Sweden.

His friend, in turn, reached out to the U.S. embassy in Oslo, Norway. The crash was reported to have occurred during a NATO exercise 21 years earlier, and Pilger’s widow had remarried. They didn’t know of any children. In 1993, computer searches weren’t as advanced as they are today.

A Navy commander at the embassy told Krogstad that he wore the same ring and would make it his mission to return the ring to Pilger’s family.

That was the last Krogstad heard about it, until this year. His query to the embassy weeks later went unanswered. Life went on.

Across the globe, in San Diego, Abby Boretto was preparing last year for her 50th birthday party to be held this year. The mother of three grown children works as a model, does volunteer work and wears the crown of Mrs. All-Star California 2021.

During the pandemic, she began preparing for her half-century milestone by exploring memory boxes of photos, letters and other memorabilia.

“I wanted to take time to learn where I’ve been, what I learned and where I’m going,” she explains. “I have struggled my whole life with ‘Who am I?’ and What am I here to do?’”

She was 15 months old when her father died, so she has no memories of him. Her mother remarried when she was 8, and she grew up in a loving, supportive family. Nevertheless, she says her dad’s passing left a void in her heart. His absence was a missing piece of her life puzzle.

“My father wasn’t unthought of, but because he died when I was so young, he was always there — but never there. So life went on.”

Relatives occasionally remarked that her mannerisms, her bigger-than-life personality and her nose and facial structure reminded them of her dad, whom they called “Rick.”

“Oh, my God, you look just like your father right now,” she was told on several occasions.

Her dad was a rising star. He had been recommended for the Naval Academy by Robert F. Kennedy (that letter is in Boretto’s memory box). He had been named a company commander during his first class year and was nicknamed “Captain Easy.”

The Naval Academy Class of ’70 40th reunion book describes him as a standout in math and all sports, a gifted leader and “the kind of guy everybody liked being around with his easy-going charisma.”

When Boretto was young, her mother, since deceased, gave her the U.S. Naval Academy sweetheart ring given to her by her husband. t was a smaller version of Pilger’s ring, except the blue star sapphire was circled by small diamonds. The ring represented both her mother and father.

“I wore it every day,” says Boretto. “It was my piece of him.”

She wore it, that is, until she was swimming while on vacation in Hawaii and it slipped off her finger. The ring was forever lost in the ocean despite efforts to recover it.

In her memorabilia, she found her dad’s last postcard to her mom, written four days before he perished. She emptied a brown envelope her mother received in 1994 that contained his class ring and a letter from Dr. Hans Krogstad explaining where he had found it. Boretto felt guilty that no one had written to thank him.

Believing it’s never too late to say thank you, she jumped on her computer and tried to hunt down Krogstad. A Norwegian magazine article mentioned him, so she wrote to the magazine but never got a response.

Just before her 50th birthday party in mid-June, she listened to a voicemail from the Naval Academy. It said, in part: “We’re calling about your father and his class ring. Are you in possession of it?”

She thought the message was a bit strange since she’d had the ring for 27 years, but this whole saga had a mysterious aura.

What Boretto didn’t know was that Krogstad was trying to find her at the same time. In May, he had a chance run-in with a friend who had taken photos of the ring after he found it. Could he still get copies, Krogstad asked?

He got them. A few days later, his friend also emailed some pictures of Pilger and his obituary following the 1972 helicopter crash.

Once again, Krogstad approached the American embassy in Norway to try to discover the whereabouts of the ring. “I thought it would be a shame if that ring was still sitting in a drawer in the embassy.”

He also contacted the Norwegian Accident Investigation Board, where someone agreed to look into it. After a bit of detective work, he was informed that the ring was with Pilger’s daughter, Abigail, in San Diego County.

“Between 1993 and May of this year, I didn’t know that Abby even existed ... I’m so delighted to know that this woman has the ring,” Krogstad told me.

Boretto and Krogstad have not yet met or directly spoken to one another. Reporter Loholt has been the go-between, sharing information and updating both.

The next chapter in the story will be a face-to-face meeting next May in Norway, where Krogstad has offered to escort Boretto to the crash site.

She already has begun to search for families of the other crash victims (five were listed in the U.S. Marine accident report), and has been in touch with her dad’s Naval Academy classmates and reconnected with members of his family.

“I’m meeting my father for the first time,” says Boretto, who likens it to an adopted child meeting a birth parent as an adult. “It’s exciting, emotional, happy, a mystery — so many things wrapped into one.”

From The Marine Corps Association:

The Ring: A Tale Of Tragedy, Love And Serendipity

By: Kipp Hanley

Posted on August 15, 2025In the fall of 1972, First Lieutenant Henry N. Pilger was 24 years old, a newly minted Marine Corps aviator, husband and first-time father.

Known as ‘Captain Easy’ on the campus of the U.S. Naval Academy just a few years earlier, the handsome and athletic lieutenant from Syracuse, N.Y., was stationed at Marine Corps Air Station New River, N.C., with Marine Light Helicopter Squadron 167 when he got the call to participate in NATO Exercise Strong Express in Norway.

Strong Express was a huge NATO exercise designed to show the alliance’s strength during the height of the Cold War with the former Soviet Union. But as the otherwise successful exercise was nearing completion, tragedy struck on the mountainous Norwegian island of Grytoya, north of the Arctic Circle.

On Sept. 23, Pilger, the copilot, and four other Marines died when the UH-1N helicopter they were flying in crashed. They were en route to pick up Marines from the mountainside. On the flight with Pilger were HML-167 squadron mates First Lieutenant Gerald Merklinger, pilot, and crew chief Lance Corporal Pete Rodriguez. Also on board the aircraft were Captain Raymond Wilhelm “Bill” Reisner, a communications officer, and Major James Skinner, a pilot who was assigned to the headquarters element of the provisional Marine Aircraft Group for the exercise. (Executive Editor’s note: Skinner was posthumously promoted to lieutenant colonel.)

Due to the secretive nature of the exercise, the accident appeared to be the end of the story for the relatives of those who perished. Unsure of what exactly happened, Pilger’s wife and other victims’ relatives went on with their lives as best they could.

“As I heard it, my mother was so pleased he was chosen for that mission as opposed to Vietnam because no one died in NATO,” said Pilger’s daughter Abby Boretto, who was just 15 months old when her father died.

But 22 years after the accident, Pilger’s Naval Academy class ring with a beautiful blue stone and his name inscribed on the inside of the ring appeared one day in Boretto’s mailbox in Connecticut. The ring was virtually unscathed, yet it was riddled with emotion, so much so that her mother, Deborah, wanted nothing to do with it.

But Boretto kept it, packing it up each time she moved to a new house. In a way, Boretto felt like it was a sign. Two years before the surprise package, she was swimming in Hawaii and lost a replica of her dad’s ring given to her by her mother. She never gave up hope of finding it, even though it was likely somewhere at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean.

“I was swimming in the ocean, and it flew right off my finger and right into the ocean,” Boretto said. “It was a gut punch. … I was sick about it. [But] I made this strange proclamation that the ring would come back to me. … Sure enough, here comes this ring in this package.”

Boretto eventually got married and raised her children in San Diego. When Boretto turned 50 in 2021, with her children grown, she had the time to investigate the mystery of her father’s class ring. So one day, she brought out the ring and the note from the ring finder Hans Krogstad and began her search to get to know her father and how he died.

“I always knew this was a spectacular story … but all that I had was this miraculous gift, the ring, returning home to me after this large amount of time,” Boretto said. “It had been 21 years up on that mountain. This ring lasted through all of those elements, all of those years. So that is all that I had, this ghostly connection. … So, what is the rest of the story?”

In 1994, Hans Krogstad was an obstetrician living in a tiny Norwegian town called Harstad, just a stone’s throw from Grytoya. He often would hunt birds on the island. One clear September day, shotgun in hand, he stumbled upon what he thought was debris from a nearby airfield.

When he looked closer, he found the remains of a glove and a gold ring, set with a beautiful blue stone, lying on the rocky landscape. He scooped it up for further examination and saw Pilger’s name scripted on the inside of the ring and that it was from the U.S. Naval Academy.

As the brother of a military officer and an aspiring military pilot—his vision prevented him from flying helicopters—Krogstad was hopeful that the ring could be reunited with the rightful owner. With the Internet in its infancy, he called his friend at the U.S. Embassy in Oslo to see if he could assist him. Eventually, a Navy attaché who graduated from the Naval Academy was able to send the ring across the Atlantic Ocean.

Not knowing whether it reached Pilger’s family, Krogstad went on with his life but never forgot about the trinket he had found. Before giving it to the attaché, he had a coworker take a picture of the ring. A few years after mailing off the ring, the widespread use of GPS allowed him to accurately determine the coordinates of his discovery.

Fast forward more than 20 years later and Krogstad happened to run into his former colleague in a local shop. He asked whether he still had the images he took in 1994 so he could digitize them. Within a week, he had the photos, further fueling his interest in finding the family.

A series of phone calls with various government employees ultimately resulted in Krogstad finding out that not only had the family received the ring, but Pilger had a daughter who was looking to reunite with the person who found it.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, Boretto had already found out what happened to her dad thanks to Freedom of Information Act requests (the documents were now declassified) and assistance from a Marine who was there that day. Sergeant Rocky Shaw was serving in the NATO exercise in the same unit that Skinner was assigned to [H&MS-31] when he first heard about the crash. Serving on board USS Inchon (LPH-12), which was anchored 40 miles from the island, Shaw knew a helicopter had gone missing that day and remained curious about what exactly happened. Eventually he found Boretto on Facebook in 2021—coincidentally, while she was visiting her dad’s old stomping grounds in Syracuse to find out more about what he was like as a child. Soon Boretto and Shaw began sharing crash reports, with Shaw helping to fill in the gaps about the mission.

Boretto and Shaw began to track down descendants of the others who died in the crash. As they connected with the Marines’ relatives, the idea for a documentary was now buzzing inside Boretto’s head, but she had no idea how to make one. One day, her aunt told her about a similar ring recovery documentary about World War II. She immediately contacted the grandson of the featured WW II veteran and, within 24 hours, was on the phone with him about creating her own project.

At the same time, Aleksander Viksund, a friend of Krogstad’s and former second lieutenant in the Norwegian Army, had recently read about the crash in a story by a local journalist and thought it was a good idea to memorialize the Marines who died that day.

So Viksund assembled a team of local residents to make a plaque and mount it on the rock-strewn crash site, which lies more than 2,600 feet above sea level. The plaque contains the victims’ names, the preliminary message report of the accident and a helicopter engraved over the words “Have Guns – Will Travel”—the HML-167 slogan.

“For Dr. Krogstad and me, it was important to do the five Marines this honor,” Viksund wrote to Leatherneck in an email. “We both grew up in the Cold War days and think that the effort of our allies is not to be taken lightly. It is a big deal for most of us living here up in the high north that young men and women from our allies are willing to serve in our country to help us keep the bullies in the East at bay.”

“He said, ‘This is part of the history of the island,’” Krogstad said. “ ‘They lost their lives preserving the peace of Norway.’ And I said, ‘That is a good idea.’ ”

In 2022, Boretto, a handful of crash victim relatives and several Marines past and present came to Norway for the unveiling of the memorial. Boretto saw Krogstad in-person for the first time that day on the mountainside, experiencing a rush of excitement from meeting the man who preserved her father’s memory for her.

“I thought going into it, I would be really emotional, but that wasn’t the feeling at all,” Boretto said. “I was super invigorated. … I felt like it was a release; I finally had met my father for the first time.”

For Krogstad, meeting Boretto was the culmination of curiosity and a bit of old-fashioned luck, or what some would describe as fate.

“It’s a strange story,” Krogstad said. “If I hadn’t had met my medic, who took a photograph of the ring, it [the story] probably would have ended there.”

Boretto’s documentary “The Ring and the Mountain” was eventually unveiled in January of 2024 on board the USS Midway Museum, located on the San Diego shoreline. The event was held on what would have been Pilger’s 76th birthday. According to pilot Wilhelm Reisner’s sister Nancy Paxton, she could not look at a photo of her brother without getting emotional until her trip to San Diego for the documentary debut. While it was not cathartic in every sense, the trip did help her deal with her brother’s death a little better.

Manuel Rodriguez, younger brother of crew chief LCpl Pete Rodriguez, also attended the event. Upon learning of the details of his brother’s death while defending freedom overseas, Manuel started to look at him as a hero. In fact, he fought—albeit unsuccessfully—to get a nearby elementary school named after his sibling.

Health issues prevented Skinner’s daughter Linda Wood from attending the memorial ceremony in California. However, the work done to unite the families of the deceased and to highlight the Marines has left “her heart full.”

“There are no words to say how proud I am and grateful for everybody that stepped up to do these stories and remember these five Marines,” Wood said. “And not just my dad, but on behalf of so many. There are hundreds of thousands of families that have gone through the same loss. These men and women, they put their lives on the line. They are so dedicated.”

Viksund said his Norwegian community has made “friends for life” thanks to the efforts from folks like Boretto, Shaw and Colonel Slick Katz, USMC (Ret), who serves on the USMC/Combat Helicopter and Tiltrotor Association board of directors and assisted in the search for the victims’ relatives. Katz served with HML-167 during the Vietnam War and presented a plaque and letters of appreciation from the squadron at the memorial’s dedication.

“We were amazed at how thankful the family members were of our efforts, and how much the efforts were appreciated by the U.S. Marines,” Viksund wrote. “We are very happy that this meant so much for the families, the USMC and the squadron HML-167.”

The Ring and The Mountain

Released on August 18, 2025.

The "category" links below lead to lists of related Honorees; use them to explore further the service and sacrifice of alumni in Memorial Hall.