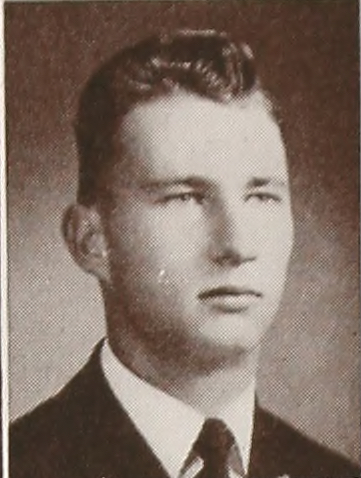

HERMAN L. DRISKELL, JR., 2LT, USA

Herman Driskell, Jr. '50

Herman Lamar Driskell, Jr. was admitted to the Naval Academy from Louisiana on July 10, 1946 at age 19 years 8 months. He left sometime after October 1947 and before September 1948. (Unable to determine details because the 1948 edition of the US Naval Academy Register isn't scanned or available.)

Lucky Bag

Herman is listed with "Those We Left Behind" in the 1950 Lucky Bag.

Loss

Herman was among 98 allied soldiers lost at or immediately after the Battle of Chonan on July 6, 1950 in combat with vastly superior North Korean forces.

His battalion, the 1st Battalion of the 34th Infantry Regiment, was nearly destroyed in the battle; it suffered a loss of nearly two thirds of its manpower and most of its heavy equipment. He was a member of A Company.

Other Information

He was taken Prisoner of War while fighting the enemy in South Korea on July 6, 1950, forced to march to North Korea on the "Tiger Death March", and shot by a guard on a train to Manpo, North Korea on September 7, 1950. Some records cite originally from Georgia, family later lived in Monroe, Louisiana.

The Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency also gives his date of death as September 7, 1950 (while in captivity).

From Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency:

In October 1950, a North Korean Army major referred to as "The Tiger" took command of more than 700 American service men who had been captured and interned as prisoners of war (POWs). In August 1953 following the signing of the armistice, only 262 of these men returned alive. One of the survivors, Army Private First Class Wayne A. "Johnnie" Johnson, risked his life during his imprisonment by secretly recording the names of 496 fellow prisoners who had died during their captivity.

Herman was reported killed in action as early as August 24, 1950.

From Richland Roots:[1]

Second Lieutenant Driskell was awarded the Purple Heart, the Combat Infantryman’s Badge, the Prisoner of War Medal, the Korean Service Medal, the United Nations Service Medal, the National Defense Service Medal, the Korean Presidential Unit Citation and the Republic of Korea War Service Medal.

One fact that has been verified concerning Lt. Driskell’s death was that he met his end in heroic fashion, in a manner that reveals the worth of his Christian and American rearing. Last report of his action was that given by survivors of his Regiment, the 34th. He left the group to take one of his wounded men to the rear to receive attention. He was last seen crossing a rice field, supporting the wounded soldier. Thus the last known act of the Louisiana soldier was his attempt to give aid and succor to a fellow soldier. That fact should be of comfort to his grieving family, and a source of inspiration to the many who join his family in grief for the passing of this fine young man.

Lt. Driskell is survived by his parents, Rev. and -Mrs. Herman Driskell, Sr. of Alto, and a sister, Miss Hermione Driskell, music supervisor in the Monroe schools.

–

Lt. Lamar Driskell, Jr., was a graduate of Neville High School and attended Tech, and later entered Annapolis. He enlisted in the Naval Air Corp in February, 1944. His father, a Baptist minister, formerly of Monroe, moved to his country home in Alto several years ago. In addition to his parents, he is survived by his sister. Miss Hermione Driskell of Monroe. He is connected to many of the prominent parish families.

Herman is buried in Louisiana.

Wartime Experience

Herman is mentioned in the book "Combat Actions in Korea:"

The battalion commander walked down the road between Companies A and B, stopping to talk with a group of 17 men manning a roadblock on Company A’s side of the road. Lt. Herman L. Driskell was in charge of the group, which consisted of an eight-man machine-gun squad from his 1st Platoon, and three 2.36-inch bazooka teams from the Weapons Platoon.

After telling Driskell to get his men down in their holes because he planned to register the 4.2-inch mortars, the battalion commander walked west across the soggy rice paddies toward Company A’s command post on top of the hill. Lieutenant Driskell’s men did not, however, get into their holes—the holes were full of water. A Weapons Platoon sergeant, SFC Zack C. Williams, and PFC James O. Hite, were sitting near one hole. “I sure would hate to have to get in that hole,” Hite said. In a few minutes they heard mortar shells overhead, but the shell bursts were lost in the morning fog and rain. In the cold rain, hunched under their ponchos, the men sat beside their holes eating their breakfast ration.

The entire 1st Platoon was also in the flat rice paddies. Lieutenant Driskell’s seventeen men from the 1st and the Weapons Platoons who were between the railroad and road could hear some of the activity but they could not see the enemy because of the high embankments on both sides. Private Hite was still sitting by his water-filled hole when the first enemy shell exploded up on the hill. He thought a 4.2-inch mortar shell had fallen short. Within a minute or two another round landed near Osburn’s command post on top of the hill. Private Hite watched as the smoke drifted away.

“Must be another short round,” he remarked to Sergeant Williams.

“It’s not short,” said Williams, a combat-experienced soldier. “It’s an enemy shell.”

Hite slid into his foxhole, making a dull splash like a frog diving into a pond. Williams followed. The two men sat there, up to their necks in cold, stagnant water.

It was fully fifteen minutes before the two Company A platoons up on the hill had built up an appreciable volume of fire, and then less than half of the men were firing their weapons. The squad and platoon leaders did most of the firing. Many of the riflemen appeared stunned and unwilling to believe that enemy soldiers were firing at them.

About fifty rounds fell in the battalion area within the fifteen minutes following the first shell-burst in Company A’s sector. Meanwhile, enemy troops were appearing in numbers that looked overwhelmingly large to the American soldiers. “It looked like the entire city of New York moving against two little under-strength companies,” said one of the men. Another large group of North Korean soldiers gathered around the tanks now lined up bumper to bumper on the road. It was the best target Sergeant Collins had ever seen. He fretted because he had no ammunition for the recoilless rifle. Neither could he get mortar fire because the second enemy tank’s shell had exploded near the 4.2-inch mortar observer who, although not wounded, had suffered severely from shock. In the confusion no one else attempted to direct the mortars. Within thirty minutes after the action began, the leading North Korean foot soldiers had moved so close that Company A men could see them load and reload their rifles.

Hite slid into his foxhole, making a dull splash like a frog diving into a pond. Williams followed. The two men sat there, up to their necks in cold, stagnant water.

It was fully fifteen minutes before the two Company A platoons up on the hill had built up an appreciable volume of fire, and then less than half of the men were firing their weapons. The squad and platoon leaders did most of the firing. Many of the riflemen appeared stunned and unwilling to believe that enemy soldiers were firing at them.

About fifty rounds fell in the battalion area within the fifteen minutes following the first shell-burst in Company A’s sector. Meanwhile, enemy troops were appearing in numbers that looked overwhelmingly large to the American soldiers. “It looked like the entire city of New York moving against two little under-strength companies,” said one of the men. Another large group of North Korean soldiers gathered around the tanks now lined up bumper to bumper on the road. It was the best target Sergeant Collins had ever seen. He fretted because he had no ammunition for the recoilless rifle. Neither could he get mortar fire because the second enemy tank’s shell had exploded near the 4.2-inch mortar observer who, although not wounded, had suffered severely from shock. In the confusion no one else attempted to direct the mortars. Within thirty minutes after the action began, the leading North Korean foot soldiers had moved so close that Company A men could see them load and reload their rifles.

About the same time, Company B, under the same attack, began moving off of its hill on the opposite side of the road. Within another minute or two Captain Osburn called down to tell his men to prepare to withdraw, “but we’ll have to cover Baker Company first.”

Company A, however, had no effective fire power and spent no time covering the movement of the other company. Most of the Weapons Platoon, located on the south side of the hill, left immediately, walking down to a cluster of about fifteen straw-topped houses at the south edge of the hill. The two rifle platoons on the hill began to move out soon after Captain Osburn gave the alert order. The movement was orderly at the beginning although few of the men carried their field packs with them and others walked away leaving ammunition and even their weapons. However, just as the last two squads of this group reached a small ridge on the east side of the main hill, an enemy machine gun suddenly fired into the group. The men took off in panic. Captain Osburn and several of his platoon leaders were near the cluster of houses behind the hill re-forming the company for the march back to Pyongtaek. But when the panicked men raced past, fear spread quickly and others also began running. The officers called to them but few of the men stopped. Gathering as many members of his company as he could, Osburn sent them back toward the village with one of his officers.

By this time the Weapons Platoon and most of the 2d and 3d Platoons had succeeded in vacating their positions. As they left, members of these units had called down telling the 1st Platoon to withdraw from its position blocking the road. Strung across the flat paddies, the 1st Platoon was more exposed to enemy fire. Four of its men started running back and one, hit by rifle fire, fell. After seeing that, most of the others were apparently too frightened to leave their holes.

As it happened, Lieutenant Driskell’s seventeen men who were between the railroad and road embankments were unable to see the rest of their company. Since they had not heard the shouted order they were unaware that an order to withdraw had been given. They had, however, watched the fire fight between the North Koreans and Company B, and had seen Company B leave. Lieutenant Driskell and Sergeant Williams decided they would hold their ground until they received orders. Twenty or thirty minutes passed. As soon as the bulk of the two companies had withdrawn, the enemy fire stopped, and all became quiet again. Driskell and his seventeen men were still in place when the North Koreans climbed the hill to take over the positions vacated by Company B. This roused their anxiety.

“What do you think we should do now?” Driskell asked.

“Well, sir,” said Sergeant Williams, “I don’t know what you’re going to do, but I’d like to get the hell out of here.”

Driskell then sent a runner to see if the rest of the company was still in position. When the runner returned to say he could see no one on the hill, the men started back using the railroad embankment for protection. Nine members of this group were from Lieutenant Driskell’s 1st Platoon; the other eight were with Sergeant Williams from the Weapons Platoon. A few of Lieutenant Driskell’s men had already left but about twenty, afraid to move across the flat paddies, had stayed behind. At the time, however, Driskell did not know what had happened to the rest of his platoon so, after he had walked back to the vicinity of the group of houses behind the hill, he stopped at one of the rice-paddy trails to decide which way to go to locate his missing men. Just then someone walked past and told him that some of his men, including several who were wounded, were near the base of the hill. With one other man, Driskell went off to look for them.

By the time the panicked riflemen of Company A had run the mile or two back to Pyongtaek they had overcome much of their initial fear. They gathered along the muddy main street of the village and stood there in the rain, waiting. When Captain Osburn arrived he immediately began assembling and reorganizing his company for the march south. Meanwhile, two Company C men were waiting to dynamite the bridge at the north edge of the village. One of the officers found a jeep and trailer that had been abandoned on a side street. He and several of his men succeeded in starting it and, although it did not run well and had apparently been abandoned for that reason, they decided it would do for hauling the company’s heavy equipment that was left. By 0930 they piled all extra equipment, plus the machine guns, mortars, bazookas, BARs, and extra ammunition in the trailer. About the same time, several men noticed what appeared to be two wounded men trying to make their way along the road into Pyongtaek. It was still raining so hard that it was difficult to distinguish details. Pvt. Thomas A. Cammarano and another man volunteered to take the jeep and go after them. They pulled a BAR from the weapons in the trailer, inserted a magazine of ammunition, and drove the jeep north across the bridge, not realizing that the road was so narrow it would have been difficult to turn the vehicle around even if the trailer had not been attached.

During the period when the company was assembling and waiting in Pyongtaek, Sergeant Collins, the platoon sergeant who had joined the company the day before, decided to find out why his platoon had failed to fire effectively against the enemy. Of 31 members of his platoon, 12 complained that their rifles would not fire. Collins checked them and found the rifles were either broken, dirty, or had been assembled incorrectly. He sorted out the defective weapons and dropped them in a nearby well.

Two other incidents now occurred that had an unfavorable effect on morale. The second shell fired by the North Koreans that morning had landed near Captain Osburn’s command post where the observer for his 4.2-inch mortars was standing. The observer reached Pyongtaek while the men were waiting for Cammarano and his companion to return with the jeep. Suffering severely from shock, the mortar observer could not talk coherently and walked as if he were drunk. His eyes showed white, and he stared wildly, moaning, “Rain, rain, rain,” over and over again. About the same time, a member of the 1st Platoon joined the group and claimed that he had been with Lieutenant Driskell after he walked toward the cluster of houses searching for wounded men of his platoon. Lieutenant Driskell with four men had been suddenly surrounded by a group of North Korean soldiers. They tried to surrender, according to this man, but one of the North Korean soldiers walked up to the lieutenant, shot him, and then killed the other three men. The narrator had escaped.

Memorial Hall Error

Herman is listed as a "Jr." on his headstone and in the Lucky Bag, but not in Memorial Hall on either the class or killed in action panels.

References

- ↑ Previously accessible at https://richlandroots.com/2019/05/19/herman-lamar-driskell-jr-killed-in-korean-war-ca-1950/

The "category" links below lead to lists of related Honorees; use them to explore further the service and sacrifice of alumni in Memorial Hall.