JOHN A. BUTLER, LTCOL, USMC

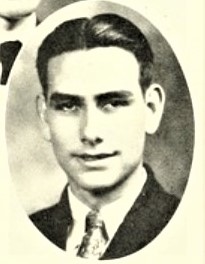

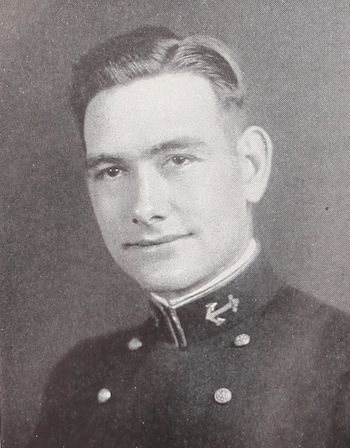

John Butler '34

Lucky Bag

From the 1934 Lucky Bag:

JOHN AUGUSTUS BUTLER

New Orleans, Louisiana

"Johnny" "Long John" "Black John" "Creole John" "Cajun"

WHY Long John ever came to the Academy has long been a mystery to many of his classmates, especially to his wife. And how he managed to stay here has been a mystery even to some of the profs. That doesn't mean that he's wooden, for he's not. He's really savvy when he wants to be — in some things anyway. The main trouble with him is that he's terribly lazy.

At heart Johnny is a radical. Not the kind of a radical you find in math either for he hates the stuff. He's the kind of a guy you would expect to see in Hyde Park standing on a soap box shouting "Down with Intolerance! Liberty, Justice, Equality for all!"

Johnny's real passion is to be a writer. Day and night he keeps pounding out stories till that typewriter of his nearly burns up. Some of the stories are good and some are pretty poor but he doesn't get discouraged. He finally had one accepted the other day and — but that's another story.

As a Romeo Johnny takes first prize — at least in his own estimation. He won't go to a hop unless he's dragging — and — I believe he did miss one hop. And whenever he drags he usually falls hard. But then each time he goes on leave he always comes back with a new O.A.O. But let me give any of you prospective O.A.O's a word of warning. Don't accept him! You couldn't possibly live with him because — because — he SINGS!

Crew. Basketball. Trident. G.P.O.

JOHN AUGUSTUS BUTLER

New Orleans, Louisiana

"Johnny" "Long John" "Black John" "Creole John" "Cajun"

WHY Long John ever came to the Academy has long been a mystery to many of his classmates, especially to his wife. And how he managed to stay here has been a mystery even to some of the profs. That doesn't mean that he's wooden, for he's not. He's really savvy when he wants to be — in some things anyway. The main trouble with him is that he's terribly lazy.

At heart Johnny is a radical. Not the kind of a radical you find in math either for he hates the stuff. He's the kind of a guy you would expect to see in Hyde Park standing on a soap box shouting "Down with Intolerance! Liberty, Justice, Equality for all!"

Johnny's real passion is to be a writer. Day and night he keeps pounding out stories till that typewriter of his nearly burns up. Some of the stories are good and some are pretty poor but he doesn't get discouraged. He finally had one accepted the other day and — but that's another story.

As a Romeo Johnny takes first prize — at least in his own estimation. He won't go to a hop unless he's dragging — and — I believe he did miss one hop. And whenever he drags he usually falls hard. But then each time he goes on leave he always comes back with a new O.A.O. But let me give any of you prospective O.A.O's a word of warning. Don't accept him! You couldn't possibly live with him because — because — he SINGS!

Crew. Basketball. Trident. G.P.O.

Loss

John was killed in action on March 5, 1945 on Iwo Jima. He was commanding officer, 1st Battalion, 27th Marines.

From LtCol John Butler and 1st Battalion, 27th Marines:

THE DEATH OF LTCOL BUTLER

About 1300, LtCol Butler mounted his jeep to head back to the regimental command post. With him were his driver, Pfc Stanley Barnett, and his radio operator. As the jeep bounced across country just west of the road junction, a Japanese 47mm antitank gun in the 3rd Marine Division sector fired. Struck by a direct hit, the jeep was destroyed, wounding the two enlisted Marines. LtCol John Butler was killed instantly. For his heroism leading LT 1/27 during the Iwo Jima campaign, the skipper would receive a posthumous Navy Cross.

Pfc Chuck Tatum, B 1/27, remembered the reaction: "The word about [LtCol Butler’s] death swept through the ranks of the 1st Battalion like a wildfire. It was whispered from position to position. Those bastards got the Colonel! The news was a shock. A stillness fell on the battalion. The loss of LtCol Butler was hard to take. If the leader has fallen, who will be next? Morale was affected. LtCol Butler was an admired and respected officer and leader of men."

Doctor James Vedder, battalion surgeon of 3/27, related the following conversation with his commander, LtCol Donn Robertson, about LtCol Butler's death: "While the coffee was brewing on our Coleman stove, Colonel Robertson stopped in for one of his routine visits. As he settled slowly to the ground to accept a cup of hot coffee, he appeared both weary and worried. His usual calm self-assurance seemed shaken for the first time.

"What's gone wrong, Colonel?"

"Plenty, the Nips bagged Butler's jeep at a road junction southwest of here."

"How bad is he hurt?"

"Killed instantly."

"Who'll take over the 1st Battalion?"

"Wornham is sending up Colonel Duryea from regimental headquarters."

"I hope he can fill Butler's shoes…"After the skipper died, LtCol Duryea, regimental operations officer, was sent to take over LT 1/27. On 6 March, the battalion spent the day in the assembly area. The line companies reorganized as well as they could. The next two days, companies and platoons were deployed individually to support other elements of the 27th Marines. Able went to LT 2/27, and remained there during the next several days. The objective was to push toward Kitano Point to Iwo Jima’s north coast.

This blurb is from a very long, multi-page story; it discusses John throughout. It seems to have been rewritten in 2020.

Other Information

From researcher Kathy Franz:

John graduated from St. Paul’s College, Covington, Louisiana. He attended Southwestern Louisiana Institute and Loyola University where he was in the College of Arts and Science and a member of the Spanish Club.

He was appointed to the Naval Academy by U. S. Senator E. S. Broussard.

His family lived in Lafayette when his father Ford was superintendent for the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company. His father was later transferred to New Orleans.

John married Emma Denise Wright on June 12, 1936, in New Orleans.

His wife was listed as next of kin.

He was also survived by his mother, Emily; his sister Emile; his brother Clinton; and his "four young children" -- the oldest John, graduated the Naval Academy in 1961. His daughter, Mary, died in 2010.

Photographs

1/27 on Iwo

From the Marine Corps Association Magazine:

By: John A. Butler III

Posted on June 15, 2025The 1st Battalion, 27th Marine Regiment was one of nine infantry battalions of the 5th Marine Division activated in early January 1944 at Camp Pendleton, Calif. Salted with disbanded Raiders, ParaMarines, and other combat veterans from earlier Pacific battles, the battalion was destined to play a crucial role in the Battle of Iwo Jima.

Among the veteran NCOs reporting to 1/27 was Gunnery Sergeant John Basilone, the Guadalcanal national hero, who requested relief from a national bond tour so he could get back in the war. The quality of training and battle leadership provided by the presence of these veterans was invaluable.

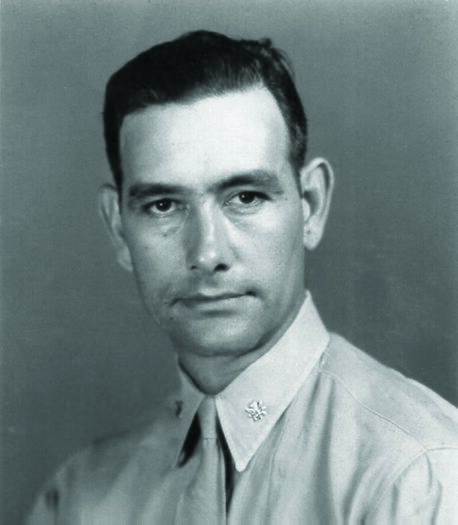

Assigned to command the battalion was Lieutenant Colonel John A. Butler, a native of New Orleans, La., and a career Marine who had graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1934. Butler had early sea duty in the Caribbean, where his linguistic skills led him to work in naval intelligence and as an attaché in the Dominican Republic. He also had duty with 1st Bn, 5th Marines from 1938 to 1940. Fresh out of Command and Staff Course, though not yet having experienced Pacific combat, this seasoned Marine officer was eager and prepared for command.

With the arrival of new men and veterans, training progressed from individual combat training to unit training. The battalion, and the entire division, trained for serious amphibious assault combat and selected “The Spearhead” as their nickname and division shoulder patch.

On Aug. 12, 1944, the 27th Marines left San Diego for Camp Tarawa in Hawaii. There in the high windswept volcanic desert, the battalion completed its final phase of training before combat. On Dec. 31, the battalion deployed for rehearsal landings at Maui, followed by a final liberty in Pearl Harbor before sailing westward aboard the USS Hansford (APA-106). Two days out of Pearl, LtCol Butler announced to his battalion that they were destined for Iwo Jima, a Japanese island objective closer to Japan than any other to date. He also told his men they were a designated assault team for the D-day landing. A sober silence fell over the battalion.

After stopping at Eniwetok for some swimming and mail call, Hansford proceeded to Saipan, where a final rehearsal was held, and the assault elements of the battalion transferred to three tank landing ships, which carried the amtracs assigned to transport 1/27 to Red Beach 2.

On D-day, Feb. 19, 1945, the assault elements of 1/27, on the heels of the first wave of armored amtracs, began coming ashore at exactly 9:02 a.m. Landing on their left was 2/27 on Red 1, and on their right, 1/23 from 4thMarDiv on Yellow 1. 1/27, as the right-flank battalion of 5thMarDiv, was tasked with the D-day mission of securing the southern end of Motoyama Airfield just inland from Red Beach 2 and advancing on order to the 0-1 Line, drawn on a map, representing the final D-day objective. Their secondary mission was to maintain contact with the 4th Marine Division. The 28th Marines, landing on Green Beach, were tasked with cutting off the head of Iwo Jima, Mount Suribachi.

On the extreme right, landing on Blue Beach, the 25th Marines of 4thMarDiv were assigned to secure the high ground overlooking the landing beaches. Enfilade fire from the high ground on the right and plunging fire from Mount Suribachi on the left pummeled the landing beaches and follow-on reserve units as the assault battalions struggled up the sand-studded terraces to reach their objectives.

LtCol Butler, who had landed on Red 2 in the fourth wave, with his assault elements, established his initial command post on a sand-covered blockhouse that still housed enemy troops, some of whom were attempting to escape from the onrushing assault. Initially, resistance was light, but that soon changed.

General Kuribayashi’s gunners unleashed their mortars and artillery. Company B of 1/27 landed out of position and soon became disorganized and ridden with casualties. GySgt Basilone, who led the machine-gun platoon of Co C, wasted no time. He immediately took control of a lost machine-gun squad from Co B and directed them toward a blockhouse that was causing serious trouble. Private First Class Chuck Tatum described that action in his book “Red Blood, Black Sand.” This was the first of several heroic actions Basilone performed in those first hours ashore as the battalion fought to gain their objective. Two hours after landing, Basilone, one of the Marine Corps’ legendary fighters of World War II, lay bleeding and dying from multiple fragment wounds caused by mortars. For his actions on D-day, John Basilone was posthumously awarded a Navy Cross.

LtCol Butler, accompanied by his radio operator, moved up to the top of the airstrip for better observation. From there, he could clearly see the disorganization of Co B, so he directed Co A to replace them on the right. Returning across the fire-swept area under observation of snipers in wrecked aircraft, he led Co A forward on a sweep that, along with Co C’s advance on the left, gained the southern end of Motoyama Airfield No. 1 by midafternoon.

Though the battalion was far short of its D-day objective, 1/27 was the only Marine unit to secure any part of Motoyama Airfield No. 1 by the end of D-day. Their first night on Iwo Jima was uneventful except for some infiltration attempts and intermittent enemy mortar fire. The enemy shifted their main fire to the now-crowded landing beaches, turning it into a junkyard of wrecked landing craft tanks and vehicles. D-day was costly, and on the morning of D+1, 1/27 was ordered into regimental reserve.

However, they did not rest but instead followed 3/27 in trace, mopping up bypassed positions as the drive for the O-1 Line continued. Despite its reserve position, 1/27 continued to suffer casualties from enemy mortar fire, snipers and firefights at bypassed positions. Despite sizeable gains by 3/27 and 4thMarDiv securing a good portion of the airstrip, the O-1 Line was still not reached by day’s end. That night the battalion established a defensive position in depth behind 3/27.

On D+2, the 27th Marines went into reserve as the 26th Marines made a passage of lines and continued the drive toward the O-1 Line just north of the airstrip. Meanwhile, the 28th Marines remained fully occupied with Mount Suribachi. However, by midafternoon, a gap between 5th and 4thMarDiv had developed, and 1/27 was directed to fill it. Moving into this gap, the battalion prepared hasty defensive positions before darkness set in. That night, Japanese aircraft, including kamikazes, launched an air raid against the fleet offshore. The attack sank the escort carrier Bismarck Sea (CVE-95) and heavily damaged the Saratoga (CV-3), taking her out of the war. At midnight, the Japanese conducted a ground counterattack, concentrated against 1/27.

The attack was stopped cold by the battalion’s 81 mm mortar platoon, interlocked machine guns, and on-call artillery from the 13th Marines. This was one of very few Japanese counterattacks during the entire campaign, and one can speculate it was planned to take advantage of the gap in the lines or the distraction of the off-shore air raids.

Daybreak on D+3 found 1/27 dug in across open ground. A cold rain added to the general misery of three days of combat. Once again, the 26th Marines affected a passage of lines and 1/27 reverted to division reserve and moved to an assembly area just northwest of Motoyama Airfield No. 1, where the Marines rested and replenished. For the first time in days, the exhausted 1/27 Marines changed socks, ate hot rations and wrote letters. They slept on the ground under ponchos or blankets. It was not an R&R center as the war thundered around them and patrols went out to hunt snipers and secure bypassed positions. No place on Iwo Jima was secure and comfortable, but for the Marines of 1/27, this was a break from the front lines.

On D+8, the 27th Marines were released from division reserve. 1/27 went into an assault along with 2/27 on the left and 3/27 on the right. The objective was Hill 362A and the ridge complex extending to the western beaches. These heavily fortified positions were the western anchor of Kuribayashi’s main defense line, and they chewed up 1/27 and its sister battalions. Two days of brutal combat gained a foothold but did not secure the objective. Fighting in this area was some of the most vicious of the Pacific war. Before the complex finally fell to the 28th Marines, who had rejoined the fight after resting from the capture of Suribachi, much Marine blood was shed.

2/28, commanded by LtCol Chandler Johnson, relieved 1/27 and passed through their lines to continue the attack on 362A and the adjoining ridges. In the next few days, 2/28 lost three of their six flag raisers and their battalion commander. 1/27 licked their wounds in division reserve but not for long. On D+13, March 4, 1/27 was attached to the 26th Marines and back in the attack on the right flank, adjacent to the 3rd Division zone of action just northeast of unfinished Motoyama Airfield No. 3. The battalion advanced in a column of companies along a narrow front led by Co C, which soon became casualty ridden. LtCol Butler replaced Co C with Co B, which managed to gain a difficult additional 100 yards against stiff resistance.

D+14, March 5, was a day of no offensive operations for the entire Amphibious Force, somewhat like a called time out to reorganize, rest and refit. The battalion was detached from the 26th Marines and directed to rejoin its parent regiment. As 1/27 moved to an assembly area just north of Road Junction 338, LtCol Butler asked for his jeep and driver so he could make a visit to the regimental supply dump and the 27th Marines command post. As the jeep passed through RJ 338, it was hit by a Japanese 47 mm round that had targeted the area. LtCol Butler was killed instantly. The runner and radio operator who were with him were wounded.

Word of LtCol Butler’s death swept through the battalion and was felt deeply by the men, who had appreciated his upfront leadership style and his honest personal care and respect for them, a sentiment often expressed in letters to his wife. In his last hastily penned letter from “Tojo’s Cave,” after the bloody fighting on 362A, he wrote of the men’s splendid courage. For his action on D-day and his leadership throughout the battle, he was awarded a Navy Cross.

Replacing LtCol Butler was LtCol Justin Duryea, the 27th Marines operations officer, who had been the interim commander at Pendleton in January 1944 before LtCol Butler arrived.

After a few more days in reserve, the battalion was back in the front-line action. On D+18, with Co C in the lead, Platoon Sergeant Joseph Julian became a one-man wrecking crew. Julian destroyed a number of Japanese positions in a series of furious assaults before he was mortally wounded. He was awarded a Medal of Honor posthumously.

That afternoon Duryea was severely wounded when his runner detonated a mine. The battalion command passed to Major William Tumbelston, the original battalion executive officer. With Tumbelston in command, the battalion continued in the attack for five days of hard-gained yards in the rocky terrain of northwest Iwo Jima until he also was badly wounded and evacuated on D+23. Command of the battalion then passed to Maj William Kennedy, who had been the operations officer for 3/27.

Killed in action on D+23 was First Lieutenant William Van Beest, who had taken command of Co C when the original company commander, Captain John Casey, was shot in the foot on D+1. Van Beest, who had been fighting since D-day, was a diligent and heroic company commander. He was awarded a posthumous Navy Cross.

On D+24, 1/27 advanced 350 yards to the top of a ridge from which they could see Iwo’s northern shore. The end was in sight. In fact this was the last day of fighting for the shot-up battalion that had lost three commanders and the majority of its original officers and NCOs. The ranks had become replacements and a few very exhausted originals who had somehow survived.

Ordered to a rear assembly area, the battalion reorganized into two companies (A and B) and a headquarters company. For Co B and Headquarters, there was no more fighting. Those assigned to Co A were detailed to a composite battalion formed from the remnants of 2nd and 3rd Bns, commanded by LtCol Donn Robertson, the original commander of 3/27 and the only original battalion commander in the 27th Marines still on his feet. This composite battalion, along with the 28th Marines and elements of the 26th Marines, fought in the Gorge, a brutal piece of ground that protected Kuribayashi’s headquarters. For his heroics during the fighting with the composite battalion, Private First Class Daniel Albaugh of Co A was the last of six 1/27 Marines posthumously awarded a Navy Cross.

On D+31, Co A was released from the composite battalion and rejoined 1/27. After saying farewell to their buddies at rest in the large 5thMarDiv cemetery, the remnants of 1/27 boarded a troop transport and departed the island of Iwo Jima. In 29 days of brutal combat, including Co A’s six days with the composite battalion, 1/27 lost 233 KIA or DOW and 557 WIA, for a total of 790 casualties.

This was one of the highest for the 24 battalions which fought on Iwo Jima. Only 1/26, with a total of 1,025, and 2/25, with 804, had higher casualties. Among the officers, no battalion suffered more than 1/27, which lost 11 officers KIA or DOW and another 27 WIA. Among the entire battalion staff, including two surgeons, only the S-2 and the communications officer were unscathed. Only one of the three original line company commanders, Captain John Hogan in Co A, was not a casualty. Co C had no original officers left after the loss of 1stLt Van Beest on D+23. Among the 34 officers and NCOs listed as boat team leaders for each of the amtracs with the 1/27 assault element, 31 were killed or wounded.

1/27 lost the cream of its officers, NCOs and experienced men, yet continued to fight and carry out its mission until the bitter end. Like all the units of the 3rd, 4th and 5th Marine Divisions that fought on Iwo Jima, 1/27 established forever the legacy of Marine courage and “uncommon valor,” represented by the Marine Corps War Memorial. Its short and valiant history belongs alongside other storied Marine battalions which have so nobly served our Corps and nation.

Remembrances

From LtCol John Butler and the 1st Battalion 27th Marines:

A Naval Academy graduate in the class of 1934, he was a tall, rawboned Marine with a dark complexion and sparse good looks. His southern roots were revealed in his New Orleans accent. At the academy he was nicknamed at various times, "Long John," "Black John" and "Cajun." A fluent Spanish speaker, Butler had already spent a decade of service moving between duty afloat with the 5th Marines and in Naval Intelligence.

Not only an officer of Marines, John Butler was also a husband and father. His wife, Denise, was a petite woman with light brown hair. The pair first met in 1931 during Christmas leave in Louisiana. John fell in love at first sight, but Denise proceeded with caution. The following Christmas at a watermelon party, the erstwhile Midshipman tried unsuccessfully to toss Denise into a tub of ice water to get her attention.

During his first class year, John gave Denise a miniature class ring during June Week. They decided to get married, but were forced to wait by the Marine Corps. Regulations prohibited a new officer from getting married until he had served at least two years. For several years, the couple exchanged a stream of letters back and forth as John traveled between ports of call as a seagoing Marine. Finally, on a warm summer day in 1936, John and Denise were married in a military wedding at Loyola’s Holy Name Church in New Orleans.

Before the war, the Butlers were stationed in Panama, Quantico, and the Dominican Republic. Moving from place to place was a way of life in the Corps, yet the family grew on a regular basis. Daughter Mary Jo arrived first in 1937 and son John was born in 1939. He was soon christened, “Johnny Boy.” Soon Denise, whom her husband nicknamed "Honey Gal," knew how to pack and move like a salty gunnery sergeant.

In early 1940, then-Captain Butler was assigned to the Naval Attaché office at the U. S. Embassy in the Dominican Republic. There he spent over three years collecting intelligence on Nazi agents and sympathizers in the Caribbean. Although this was an important mission, Butler wanted a combat assignment. He felt a sense of duty to get into the war and applied for transfer to the Fleet Marine Force.

The Butlers’ third child, Morey, was born in mid-1943. Late that year, then-Major Butler received a promotion and the assignment he'd dreamed about. With orders to proceed through a staff and command course at Marine Corps Base, Quantico, LtCol Butler was bound for Camp Pendleton and the 5th Marine Division. He flew on ahead to Quantico while Honey Gal packed up their household and left the Dominican Republic with the children.

Traveling by plane and train, Honey Gal and the kids made their way to join John at Quantico. The family was billeted in temporary housing and the baby, Morey, slept in a dresser drawer. Johnny Boy, who only spoke Spanish, ran around the base trying to make friends, but none of the other kids understood what he was talking about. Dad completed his course in December 1943 and the Butlers loaded up their Studebaker sedan for a long cross-country trip to California. As Honey Gal would later remember, the kids left a trail of spilt milk across the United States.

The family arrived at Camp Pendleton in mid-January 1944. In the hectic atmosphere of a division preparing for war, John was first billeted as the Executive Officer of the 27th Marines. Sadly, his father passed away in New Orleans and John returned home for nine days of emergency leave. Shortly after returning to Camp Pendleton, he was assigned to command 1/27.

…Sometimes LtCol Butler took his son, John, to the base. Johnny Boy liked riding in his dad's jeep, eating Marine chow, and hanging around with the Gyrenes of the battalion. It was all very impressive to a four-year-old boy.

The Butlers had a family pet; an Airedale named "Yaqui Boy" whom they had acquired in the Dominican Republic. LtCol Butler tried unsuccessfully to enlist Yaqui Boy as a war dog. The dog flunked K-9 boot camp, but still hung around Camp Pendleton with the Colonel and his Marines. A few days after the battalion shipped out in August 1944, Yaqui Boy ran away and the family never found him. Mrs. Butler told the children he probably got lost trying to get to Camp Pendleton to find his Marines.

From Tales Press:

Losing My Dad Before I Really Knew Him

I was 5 years old when my father, Lt. Col. John Augustus Butler, commanding the First Battalion, 27th Marine Regiment, was killed in action on Iwo Jima while leading his men from the moment they landed on Red Beach Two on Feb. 19, 1945.

Years later on a trip to Iwo Jima for the annual “Reunion of Honor” in 2005, I met and roomed with Ray Elliott. Ray asked me what it was like growing up after having lost my dad in war. Ten years later, I attempted to answer that question, having thought about it often. I also learned on that trip that Ray had written a novel, “Wild Hands Toward the Sky,” based on a young boy growing up in rural Illinois who had lost his father on Guadalcanal.

One thing I had in common with Ray’s fictional boy was a longing to search for knowledge about my dad and what he had done in the war. This longing was largely met by my mother, who always kept the image of my father alive in the stories she told about him from their short, loving life together. My father’s mother, on summer visits to our home in Florida, also told us stories of his youth, and the two I always treasured were of my dad beating up a school bully and writing a letter that was published in the New Orleans Times-Picayune after a man had poisoned the family dog. Much later in life, I learned more about my dad and his early family life in New Orleans from an aged uncle, my dad’s youngest brother, Clinton.

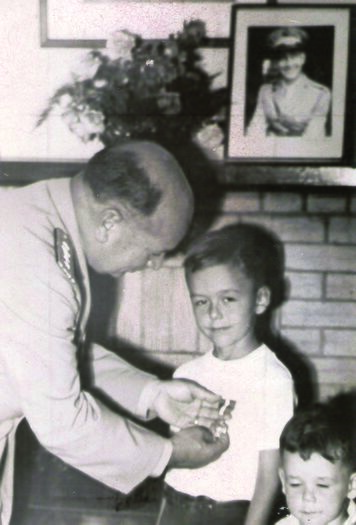

On my seventh birthday, an admiral, two Marines who had served on Iwo Jima, and Alexander Vandergrift Jr.—himself a battalion commander on Iwo with the Fourth Marine Division—came to our home on the Caloosahatchee River in western Florida to present my dad’s posthumous Navy Cross, which was pinned to my clean white T-shirt. After the ceremony, my 3-year-old brother, Morey, and I took the admiral to our chicken house to show off our many chickens. This event loomed large and resulted in a lifetime of wanting to learn more about my dad and his life as a Marine and as a leader of his battalion on Iwo Jima.

While I did learn some things from my mother about my dad’s life as a Marine from 1934 to ’45 and as a midshipman at the Naval Academy from 1930 to ’34, there was more I wanted to know, and many of these questions were answered, in part, as my life progressed to where it is now, but the quest still goes on.

I attempted to follow in my dad’s footsteps by attending and graduating from the Naval Academy and becoming a Marine officer. The academy was no easy challenge for a free-spirited youth from the wilds of Southwest Florida, but I somehow prevailed and strived to meet the high standard of manhood and values of my dad as had been passed on to me by my mother.

From Mom, and my dad’s class yearbook, I learned that he had struggled with some of the technical courses, but excelled elsewhere and had stories he’d written published in the midshipman magazine, Trident.

He was attracted to the Marine Corps by the writings of John W. Thomason, the Frederick Remington of the Marine Corps early in the last century, and was on the crew and basketball teams. He was also a good boxer, but had his nose broken when matched with the brigade champ in his weight class.

I could not play basketball, and crew was for the much rangier and taller midshipmen in our class. My sports were football in plebe year—which kept me on the training table and away from the upper class at meal times for at least three months, and track and field—where I competed as one of many pole vaulters at the academy.

I did well in boxing class, but knowing about my dad’s broken nose, I declined our boxing coach’s invitation to train and fight the then-prevailing brigade champ in my weight class, a classy fighter who never lost a fight in his four years at the academy.

In academics, I barely scraped by in electrical engineering but did better in other courses. My very best grades were in language and foreign policy. I was no academic stalwart by a long shot and had my struggles in the demerit department, particularly first-class year. When it was over in June of 1961, I wondered if my dad would have been proud of my sub-par performance as a midshipman. But I was never prouder to graduate and be commissioned a second lieutenant in the United States Marine Corps, and my mother—God bless her—was indeed proud of her newly minted Marine officer son.

From Hall of Valor:

The President of the United States of America takes pride in presenting the Navy Cross (Posthumously) to Lieutenant Colonel John Augustus Butler (MCSN: 0-4987), United States Marine Corps, for extraordinary heroism as Commanding Officer of the First Battalion, attached to the Twenty-Seventh Marines, FIFTH Marine Division, during operations against enemy Japanese forces on Iwo Jima in the Volcano Islands, from 19 February to 5 March 1945. Landing with his battalion in the fourth wave on D-Day, Lieutenant Colonel Butler quickly advanced his men over ground swept by heavy hostile mortar and artillery fire to a position approximately 150 yards inland from the beach, where he promptly established his command post on top of an enemy occupied blockhouse. Directing his troops from this dangerous position as they made their tortuous way over the shifting, volcanic sands and gun-studded terraces toward Motoyama Airfield Number One, he repeatedly exposed himself to the smashing bombardment of powerful Japanese gun-batteries and, subsequently unable to obtain satisfactory information regarding the progress of battle, unhesitatingly moved forward to the base of the airfield. With observation masked from this point, he fearlessly advanced to the top of the field, moved out under the unabated fury of hostile fire, and making a personal reconnaissance of the area, observed that his left assault company had circled the southern edge of the field but his right assault unit had been stopped in its advance by the overwhelming volume of Japanese fire. Disregarding all personal danger, he returned across the contested area under the direct fire of enemy riflemen concealed in the debris of wrecked planes and directed his right assault company forward. Cool and indomitable as the intrepid unit surged across the field in the face of savage resistance, Lieutenant Colonel Butler, by his daring combat tactics, outstanding valor and determined aggressiveness in the early critical stages of battle, had inspired his men to heroic performance during the final phase of this assault which culminated in the seizure of the entire southern end of the vital Japanese position before the close of D-plus-2. His dynamic leadership and astute military acumen throughout reflect the highest credit upon Lieutenant Colonel Butler and upon the United States Naval Service. He gallantly gave his life for his country.

General Orders: Commander in Chief Pacific Forces: Serial 35224 (September 24, 1945)

Action Date: February 19 - March 5, 1945

Rank: Lieutenant Colonel

Battalion: 1st Battalion

Regiment: 27th Marines

Division: 5th Marine Division

The "Register of Commissioned and Warrant Officers of the United States Navy and Marine Corps" was published annually from 1815 through at least the 1970s; it provided rank, command or station, and occasionally billet until the beginning of World War II when command/station was no longer included. Scanned copies were reviewed and data entered from the mid-1840s through 1922, when more-frequent Navy Directories were available.

The Navy Directory was a publication that provided information on the command, billet, and rank of every active and retired naval officer. Single editions have been found online from January 1915 and March 1918, and then from three to six editions per year from 1923 through 1940; the final edition is from April 1941.

The entries in both series of documents are sometimes cryptic and confusing. They are often inconsistent, even within an edition, with the name of commands; this is especially true for aviation squadrons in the 1920s and early 1930s.

Alumni listed at the same command may or may not have had significant interactions; they could have shared a stateroom or workspace, stood many hours of watch together, or, especially at the larger commands, they might not have known each other at all. The information provides the opportunity to draw connections that are otherwise invisible, though, and gives a fuller view of the professional experiences of these alumni in Memorial Hall.

July 1934

October 1934

January 1935

April 1935

October 1935

January 1936

April 1936

1LT Thomas Jordan '26 (Marine Corps Schools, Marine Barracks, Quantico, Virginia)

1LT Harold Bauer '30 (Aircraft One, 1st Marine Brigade, Fleet Marine Force, Marine Barracks, Quantico, Virginia)

1LT Hector De Zayas '32 (1st Marine Brigade, Fleet Marine Force, Marine Barracks, Quantico, Virginia)

2LT David McDougal '33 (1st Marine Brigade, Fleet Marine Force, Marine Barracks, Quantico, Virginia)

July 1936

1LT Harry Lang '29 (Marine Corps Schools, Marine Barracks, Quantico, Virginia)

1LT Cleo Keen '32 (Aircraft One, 1st Marine Brigade, Fleet Marine Force, Marine Barracks, Quantico, Virginia)

1LT David McDougal '33 (1st Marine Brigade, Fleet Marine Force, Marine Barracks, Quantico, Virginia)

January 1937

April 1937

September 1937

January 1938

July 1938

January 1939

October 1939

June 1940

November 1940

April 1941

The "category" links below lead to lists of related Honorees; use them to explore further the service and sacrifice of alumni in Memorial Hall.