Memorial Hall

Memorial Hall as a physical place, and a history of its use since construction in 1906, is the topic of the first article below. You can tour Memorial Hall via Google Street View.

The second article is a searing and intense account of what Memorial Hall means to the families, shipmates, and friends of the alumni whose presence gives the Hall its meaning.

Memorial Hall is not simply a place of heroes; the men and women we read about in text books, she embodies more. She silently teaches the future leaders of the Naval Academy from the experiences of her fallen. She defines the fearless determination, the gallantry, character and courage of the officers that graduate from the halls of Bancroft.

She enshrines within her walls the legacy of the everyday officers who three-hundred-sixty-five days a year put their safety, well-being, future, and dreams on the line with no questions asked for our freedom. Her fallen shipmates did not seek to be heroic, they were simply doing what they had been taught at the Academy; to lead, to protect, to “Never Give Up the Ship”. Families, friends and shipmates will forever grieve the officers whose names adorn the chambers within Memorial Hall. They will always hold dear the pride the fallen carried in their hearts serving our country.

Memorial Hall, she cradles our tears, embraces our loved ones memories, honors their valor, carries their courage, instills the Academy’s values on all who pass through her chambers. She is a constant reminder the cost of freedom is immeasurable. Memorial Hall holds the past of the Academy as well as her future not yet realized. She is simply the heart and soul of every Officer that graduates from the United States Naval Academy.

Memorial Hall Dates

Construction completed: 1906

Dont Give Up The Ship flag hung: 1924

First mural completed: 1932

Killed in action scroll installed: 1960

Major renovation; class panels added: 2003

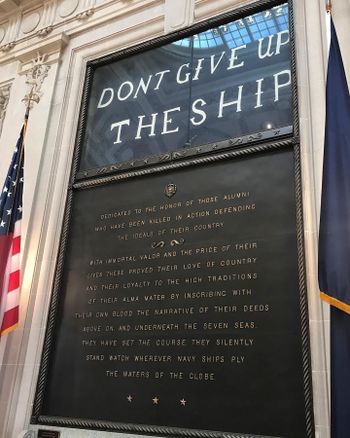

Dedication

Appearing in the center of Memorial Hall:

DON'T GIVE UP THE SHIP

Dedicated to the honor of those alumni who have been killed in action defending the ideals of their country.

With immortal valor and the price of their lives these proved their love of country their loyalty to the high traditions of their alma mater by inscribing with their own blood the narrative of their deeds above, on, and underneath the seven seas. They have set the course. They silently stand watch wherever navy ships ply the waters of the globe.

A short book on the dedication is available on Amazon.

Second Renaissance

The article below is a portion of what appeared in the September 2003 edition of Shipmate; it was written by Ginger Doyle.

Part II: Bancroft Hall's Center Section, Then and Now

Imagine being one of the first to see Bancroft Hall upon its completion in 1906. Gazing up at the dome you stand in awe of Ernest Flagg's design. From the Rotunda you descend to Recreation Hall where ornate chandeliers command your attention. Next you climb the stairs to Memorial Hall, pause to remove your hat then enter. Its limestone is pristine, its floor brilliant, and the smell of fresh paint permeates the air. It is a sacred space, a reverent space. Those who visit the Academy today are fortunate to have a similar experience. After one year of construction, Bancroft Hall's Center Section has been restored to its initial grandeur. The section, including Memorial Hall, Smoke Hall, and the Rotunda, was re-opened on 15 May 2003 and is stunning.

Memorial Hall, Then

Memorial Hall was initially designed, as its name suggests, as a place for quiet, respectful remembering. Yet by 1907, it had already become the site for less appropriate activities. A drawing by a member of that year's class shows midshipmen there playing the piano, socializing, and reading. As an interesting side note, outside of Memorial Hall one brave soul is even fishing for hats worn by unsuspecting visitors!

Fifteen years later, Academy Superintendent Rear Admiral Henry B. Wilson 1881 took a step to curb such activities in Memorial Hall. Naval Academy Order No. 49-23 was issued on 31 July 1923, which reads: (1) Memorial Hall has long been one of the honored spots at the Naval Academy and has served as a source of inspiration to all officers, midshipmen, and others who have visited it; particularly on account of the many memorials placed there honoring those officers and men of our Navy who have lent distinction by their service to country and flag. (2) In order that Memorial Hall will be restricted only to such gatherings as its atmosphere suggests its use as a reading room will be discontinued. Recreation Hall is designated for this purpose...

Still, however, Memorial Hall continued to be used in an inappropriate manner in the coming years. By the '30s it had become the site for midshipmen's club meetings such as the Naval Academy Christian Association and the Quarterdeck Society in 1935. That year Memorial Hall also featured a display of the Art Club's creations during June Week.

June was a particularly busy month for Memorial Hall in the '30s and for much of the 20th century. For it was there that Plebes took their oaths of office. As a member of the Class of 1943 recalls, "We came in at different times and were sworn in in Memorial Hall in small groups of twenty or so..." He and his Classmates stood facing the timeless message "Don't Give up the Ship" on the Battle of Lake Erie Flag. Commodore Oliver Perry hoisted the flag aboard Lawrence one hundred days after Captain James Lawrence spoke the words as he lay dying aboard Chesapeake on 1 June 1813.

However, the flag has not always been located in Memorial Hall. It was transferred from Mahan Hall's auditorium in 1924 and initially hung above Memorial Hall's central door. The flag was lowered to its present location in 1960 when Mrs. Webb Jay donated the memorial beneath it to honor her son, Lieutenant Commander John Louis Mehlig '37.

The door that the memorial and flag cover opened onto the balcony and overlooked Smoke Park. Lost when the Mess Hall was expanded, Smoke Park once served as the site for many midshipmen's social events—as did Memorial Hall.

Members of the Class of 1941 enjoyed being "Kings for a Day" in Memorial Hall on "Second Class Day." There, on about 1 August, they enjoyed a "grand dance after a day of recreation in Annapolis."

At that point, Memorial Hall was also a popular rendezvous for midshipmen and their drags—especially for underclassmen on Sundays since Smoke Hall was a "First Class rate." Those who gathered there, however, would not have seen many of Memorial Hall's current murals.

Charles Robert Patterson completed its first mural in 1932. Presented to the Academy by Mr. Edward Berwind 1869, it features Constitution and Java Engagement. Patterson finished other murals in 1936 and 1958 but died before completing the Battle of Lake Erie. Artist Howard French finished this and other murals in 1959, 1960, and 1961.

Graduates from the '60s through the present recall several other ways Memorial Hall has been used. While some remember attending post-graduation Alumni dinners and retirement ceremonies there, others recall taking ballroom dancing classes and playing its piano.

Memorial Hall, Now

Those who visit Memorial Hall today will not find midshipmen taking ballroom dancing classes there, nor will they find its former piano. Yet they will discover that its structural integrity has been improved and that its dignity and decorum have been restored.

Like Smoke Hall and the Rotunda, Memorial Hall's limestone has been cleaned and re-pointed, its ceiling has undergone extensive plaster repair and it has been repainted. Its historic light fixtures have also been restored and brought up to code. The light fixtures and new skylights give added notice to the room's murals, which appear brilliant after careful cleaning as does its wooden floor.

The space's more subtle changes are also noteworthy. Memorial Hall has been upgraded to comply with fire and safety codes and standards. Furthermore speakers, designed to match their surroundings, provide higher quality acoustics.

While contractors improved Memorial Hall's structural integrity, others restored its dignity and decorum. Crucial to this accomphshment was the Special Memorials Committee chaired by Colonel John Ripley '62, USMC (Ret.).

Comprised of graduates from the '30s through the '80s, the committee identified three categories for memorialization: Service, Sacrifice, and Valor. It was determined that Memorial Hall, as its name indicates, should solely memorialize Naval Academy alumni. As a result, only the categories of Sacrifice and Valor will be represented there in the future. Those recognized for Service will continue to be honored on The Yard in locations such as Alumni Hall.

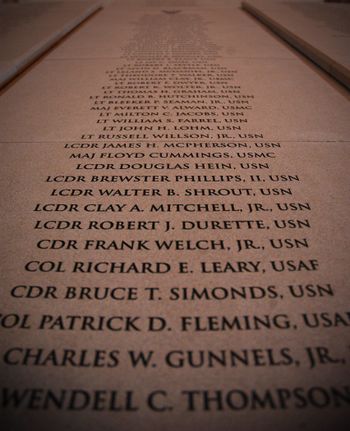

Valor is exemplified in Memorial Hall by a plaque bearing the names of those awarded Medals of Honor. Nearby, the Killed in Action scroll is a sobering, powerful example of Sacrifice. This scroll, however, does not convey the full breadth of sacrifices made by Naval Academy graduates for their country. Non-hostile "Line of Duty" Operational Losses are equally worthy of memorialization. For this reason, an Operational Losses panel is being erected in Memorial Hall.

The panel will contain the crest of each Class, followed by the Class's Operational Losses. It will bear approximately 3,800 names, each individual's rank and service, and has been designed to allow for about one century of expansion.

While an Operational Losses panel has been added to Memorial Hall, other items have been removed. The Committee's Plaques, Painting, and Memorials Subcommittee inventoried every item in Memorial Hall and the Yard. It categorized each as representing Sacrifice, Service, or Valor. Based on the current clause, the full committee then decided which items should remain, be removed from, or relocated to Memorial Hall.

A plaque recognizing the heroism of Commander Wade McClusky '26 at Midway, for example, was relocated from Dahlgren Hall. Those that remain, yet do not fall into the categories of Sacrifice or Valor were "grandfathered" in because of their antiquity and beauty.

Private funding has enabled the restoration of Memorial Hall's dignity and decorum, specifically the Classes of 1954, 1986, and 1995. The Class of '54 supported the refinishing of Memorial Hall's plaques, flags, and paintings. The original Battle of Lake Erie Flag, for instance, is currently being preserved in New York and will most likely be displayed in Preble Hall upon return. Those who graduated in '54 also enabled the development and production of the Operational Losses panels. Members of the Class of 1986 sponsored and supported the Special Memorials Committee. …

Lastly, the Class of 1995 made possible the Current Operational Losses panel, which will be replaced and updated annually.

Looking Ahead

In the future, the only functions to take place in Memorial Hall will be those that meet the standards of decorum for the space, which Colonel Ripley rightly refers to as the Naval Academy's "Sistine Chapel." Those who attend such functions will surely be delighted by its renovations and restorations.

Like Memorial Hall, Bancroft Hall's Center Section as a whole has been restored to its initial grandeur. One feature, however, still appears quite differently than it originally did: the stairs leading from the Rotunda level to Smoke and Memorial Halls. After being thoroughly cleaned, they still bear the indentations made by all who have entered Bancroft Hall since its completion, nearly one century ago.

Ginger Doyel is a fourth generation Annapolitan. History, particularly naval history, has always been of great interest to her. Her grandfathers, father, and uncle are Naval Academy graduates representing the Classes of 1943, 1945, 1968, and 1972. After receiving a degree in leadership studies from the University of Richmond ('01) she lived in Charlottesville, VA. While there she served as a research fellow for the Pew Partnership for Civic Change, illustrated and published a children's book, and began a successful golf art business. Since June of 2002, she has resided in Annapolis, MD, and is a weekly history columnist for The Capital newspaper.

Personal Remembrance

From “Lessons from Memorial Hall" by Denise Robinson on May 14, 2011:

I was eighteen the first time I entered her halls. 1981 was the beginning of my growth. I was struggling between being a teenager and becoming an adult. I had recently graduated from high school, and was in my first semester of college. Many life lessons started that evening, lessons I had not begun to realize. Men who would have a profound effect on me, change who I was, walked the corridors of Bancroft Hall in October of 1981; I had not yet met them.

He was my first real boyfriend, a 3rd class midshipman in 7th company from outside of Buffalo, New York. I loved the way he spoke; the pronunciations of certain words, beer, car, park, etc. were almost an infatuation to me. For a silly 18-year-old girl, his accent, his uniform, everything about him seemed so mature. I loved having a boyfriend and I wanted to keep him around for a while so I worked hard trying to impress him, let him know I liked him.

From the time I first sat in the kitchen splitting green beans with my grandmother I was taught a way to a man’s heart is through his stomach. My afternoon class was was canceled so I decided with my added free time I would make chocolate chip cookies and surprise my mid. With my baking complete, I bagged the cookies and headed to the Academy.

I had never surprised anyone before, and wondered as I parked my car if this was such a brilliant idea. Brushing aside my anxiety, I headed across the yard. I climbed the imposing steps to the entrance of Bancroft Hall. I marveled at the massive size of the foyer, the towering dome, and arches that adorned the ceiling. In front of me stood numerous flags, beyond them lay another massive staircase leading to a larger door with some type of strange seal of armor above it. Turning in a small circle I was in awe at the visual magnificence that surrounded me.

A sign directed me to turn left for the visitor’s reception area. At the window I informed the midshipmen on duty the company and name of whom I wished to visit. He called his company and relayed the message he had a visitor. I was directed down the hall to the visitor's lounge and told my boyfriend would be there shortly.

The lounge was crowded with midshipmen and their girlfriends. Leather couches were taken up by couples mesmerized with each other’s presence. Trying not to stare at the various scenes playing out in front of me, I stood awkwardly in the corner and waited. Within a few minutes my boyfriend entered the room. Noticing how uncomfortable I was he invited me for a walk. Happily I agreed.

We exited the lounge and headed toward the entrance. Instead of turning right to go out the doors, he paused, then told me to follow him. We headed up the staircase I had been confronted by earlier. Ascending the steps I ran my hand along the wide banister. The room that stood above us commanded my attention. The breadth and prominence of the entrance overpowered every other feature in the building. I couldn't explain why but it took my breath away with it's overpowering silence.

On the landing outside the entrance, my boyfriend laid the bag of cookies by the wall. He brushed and straightened his uniform. He checked his posture and seemed to grow an inch or two taller before me. My confused look at his uniform checks told him I had never been inside the hall. He asked if I knew the significance of the Memorial Hall, I shook my head.

He explained as a plebe he had to wait for the upper classmen to disclose all the hall represented. What it meant to the midshipmen and alumni of the Academy. Every midshipman had to earn the right to enter her chambers. To him Memorial Hall needed no further explanation. If one listened; her walls, her chambers spoke for themselves. In time they would disclose their meaning to all who sought it.

The large hall at the top of the stairs, located across from the entrance to Bancroft Hall is not just any room, she is like no other. Memorial Hall sits at the heart of Mother B; the nickname affectionately given Bancroft Hall by the midshipmen. Memorial Hall is the quintessence of the Academy. Everything the Academy represents, the values it teaches are all embodied within her walls. She holds the lessons of the past that will lead midshipmen forward; teach them to become better men and women, outstanding leaders.

From the moment I stepped within her walls I was overwhelmed. The massive hall was quiet, peaceful. The sounds of my shoes hitting her floors echoed through her towering architecture. A solemn silence resonated through the air. The mammoth columns seem to be guarding the memories of the Academy’s shipmates. Her walls divulged the stories of the Navy’s heroes, their struggles, their battles, their victories, disclosed through powerful images and baroque memorials.

Walking along her walls my boyfriend pointed out the heroes that stood out to him, officers he had studied or would study. I stood in the middle of the main room, stared upward through the large skylight, looking to the Heavens where her gallant men were surely residing. Valor and honor surrounded me.

Memorial Hall was beautiful, magnificent in her glory. An indescribable sadness came over me as I stood silent. I was new to the Annapolis; I had not yet developed ties to the Naval Academy, her midshipmen and graduates. I did not understand the strange sensation the hall gave me. I would not fully comprehend what I was feeling, the sacrifices that lay within her walls and alcoves until many years later.

I did not enter the walls of Memorial Hall again for twenty some odd years. In my forties, no longer a naïve teenager. I had gotten off work early and headed to Annapolis Mall to do some Christmas shopping. The gifts would have to wait, the sign at the end of Route 2 for the Naval Academy beckoned me. Memorial Hall was summoning me.

Awhile back I had read a feature about the re-dedication ceremony of Memorial Hall. She had undergone years of renovation. The article noted that her walls now contained panels listing former midshipmen who had been killed while serving in the military. Her alcoves made more hallow by the more than 2500 lost shipmates chronicled upon them. The ghosts and memories of the young men that once lived within the walls of Mother B. were now enshrined for all to see.

I convinced the guard to allow me to park at Preble Hall. I sat for a moment staring at the Academy grounds that I once roamed. I smiled, remembering all the friends I had made; the laughter, love and friendship I found within the Academy’s gates. I walked by the Chapel, down the path to Stribling Walk. Beyond Tecumseh lay Bancroft Hall, the cannon along the walls sitting silent vigil, announcing to all who enter Tecumseh’s court they are entering the home of American’s past, present and future leaders and heroes.

I climbed the massive stairs of Bancroft. The only facet time seemed to change was me. I stood under the rotunda at the entrance staring at the steps that once again lay in front me; my passage way to Memorial Hall. As I had done many years before I placed my hand on the banister, feeling every inch of her marble under my fingertips. My eyes fixed above on the sweeping letters that spelled “Don’t Give Up the Ship”. The memorial was flanked on one side by an American Flag and on the other a Naval Academy Flag. As I neared the top of the staircase, the more powerful the image became.

Standing at her entrance, I wondered why I had come back. Part of me wanted to see the new memorials, most of me paralyzed with fear by the emotions I knew awaited me. Two midshipmen exited the hall, nodded, acknowledging me as they passed by. The hall was now empty, safe to enter. I no longer had to worry about strangers witnessing my reaction when I first looked upon the memorial for the class of 1983.

As I had done many years before I looked up through the beautiful skylight above, this time saying a prayer for strength. Immediately I was drawn to the right side of the hall. It was as if my heart knew exactly where he was, the place where his name had been inscribed for all eternity.

I entered the alcove, walked to the corner. Before me hung a large set of marble panels, four across and eight down. Every two panels designated for an Academy class, the bottom two his class. I read, Class of Nineteen Hundred Eighty-Three; underneath the wording was the class crest. The fourth name down from the top, Lt. Robert T. Bianchi, USN. I reached out to touch him.

Tears began to roll down my cheeks as I ran my fingers over his inscription. I was taken back to the morning my phone rang and heard the words that forever changed my life, “Bobby is dead.” That day I lost my innocence.

There is something utterly wrong at seeing the name of a man whose arms once held me, whose hands wiped away my tears. The man to whom I had entrusted my secrets and dreams, a man taken from me when he was twenty-six and I was not quite twenty-four. At one time our bodies were one, joined as we made love. I remember the warmth of his skin and the tenderness of his voice the last time he touched me.

Now the pain of unexplainable separation, the years of want and hurt, streamed from my heart as tears. A river of crushed dreams played through my mind as I looked out the window. Closing my eyes, I imagined Bobby walking through the halls of Mother B, playing lacrosse on the Academy fields. I saw him smiling at me, his eyes lighting up when he first saw me standing next to the gate at the turf field. In that instant I knew he was happy to see me.

I had been lost in the memories of Bobby when I heard footsteps enter the hall. Not wanting anyone to witness my heartache I rushed down the stairs and took refuge in the bathroom. I sat in the stall wiping my tears and reprimanding myself. Bobby had been gone almost twenty years; I had made a promise long ago, no more tears, only smiles when I remembered him.

My brain had made a promise my heart could not keep. No amount of scolding would stop my tears. For years I had avoided all reminders of Bobby. I had cut ties to everyone and anything that might cause me to remember how much was lost when he died. Yet here I was standing in the institution that made him a man, the Academy he loved so much.

The core of Lt. Robert T. Bianchi enveloped me. Time seemed to fly backwards. Once again I was twenty three and lost. I had to make a decision. I could fight what I was feeling or embrace his memory and all the emotions that accompanied it. I washed the tears from my face and looked in the mirror. My eyes reflected the sorrow still within me. I took a deep breath, headed out the door and back up the steps. More valiant men deserved my respects.

I realized I could never go back to the first time I stepped within Memorial Hall. I was no longer naïve and had long given up the notion that people we love will grow old with us. I reentered the hall and faced the reality of life’s cruelty. I was gazing upon the sacrifices of the few, for the many.

I started on the left side of the hall, began reading the names of men who had died long before I was born. As I progressed through the panels, comprehending the ranks of the men listed, I became cognizant that the young die in the military. Survivors retire. I stopped to pay special tribute to the men who had been awarded the Medal of Honor. Once again I looked up through the massive skylight to Heaven, prayed for control as I reentered the alcove memorializing the most recent graduating classes. I purposely skipped the first row, Bobby’s class and started with the second.

Class of Nineteen Hundred Eighty-Four, the bottom name, Cdr. Peter G. Oswald, USN. I smiled, remembering the first time I was introduced to Pete after a football game. When I asked him what position he played he answered, offensive line. His job was to protect Nap (McCallum) and to open holes for him to run through. Pete was a force to be reckoned with on the field, and I discovered a sweet caring soul outside of the game.

I will always cherish the conversation Pete and I had at Fran O’Brian’s. He gently explained my two biggest character flaws: First, I put distance between me and the men who tried to love me. Second, I refused to see all that was beautiful within me. Until I changed I would never be happy. In 1984 I thought his remarks were callous, now I understood he was giving me much needed guidance. He cared enough to be honest.

Class of Nineteen Hundred Eighty-Five, the bottom name, Cdr. Kevin A. Bianchi, USN. Bobby’s brother. Like Pete he had died a few years before. Kevin always greeted me with a huge smile and arms spread wide for a hug. Usually the long strong embrace was followed by playful teasing, gentle ribbing. His way of trying to get me to let go of my fears and re-connect with his brother. His constant question, "What's the deal?"

Kevin was genuine. No matter what someone had done, a mistake that they had made, hurt they had inflicted, I never heard Kevin utter a bad word about anyone. He practiced and understood the importance of forgiveness. He had incredible faith in the goodness of people.

Bobby and Kevin were cut from the same cloth, they were honest, had unbelievable character, undeniable faith and courage; they were born leaders. They were extraordinary men who changed everyone who met them. I was blessed; I knew both Bobby and Kevin; even if it was for only a short amount of time.

I continued down the wall, until the stones were void of any class insignia, barren of any memories. Knowing one day these untouched stones would be transformed into memorials, inscribed with names of unknown boys and girls, children now playing in the backyards across this country, I said a prayer. I asked God for the impossible; that these stones forever remain vacant. I asked that he be gentle on the souls already enshrined within Memorial Hall.

Before leaving I went back to memorial for the class of 1983. I rested my hand on Bobby's name. My palm centered on his middle initial, almost hoping to feel his heartbeat one more time. I leaned in, whispered how much I loved him and he was missed by many. I told Bobby it was his turn to shepherd the future leaders of the military. The world was crazy, the men and women studying at the Academy needed guidance. I turned my hand over and gently caressed his name. I wiped my tears and as I had done numerous times before at his grave, I kissed my fingers, then lovingly placed them on his name before leaving.

Fearful I would break down; I quickly descended the stairs, passed under the rotunda and stepped out the front door. I walked across the yard then stopped and turned back toward Bancroft Hall. Suddenly I realized Mother B had spoken to me. I felt her soul; I understood what Memorial Hall is to me.

Memorial Hall is not simply a place of heroes; the men and women we read about in text books, she embodies more. She silently teaches the future leaders of the Naval Academy from the experiences of her fallen. She defines the fearless determination, the gallantry, character and courage of the officers that graduate from the halls of Bancroft.

She enshrines within her walls the legacy of the everyday officers who three-hundred-sixty-five days a year put their safety, well -being, future, and dreams on the line with no questions asked for our freedom. Her fallen shipmates did not seek to be heroic, they were simply doing what they had been taught at the Academy; to lead, to protect, to “Never Give Up the Ship”. Families, friends and shipmates will forever grieve the officers whose names adorn the chambers within Memorial Hall. They will always hold dear the pride the fallen carried in their hearts serving our country.

Memorial Hall, she cradles our tears, embraces our loved ones memories, honors their valor, carries their courage, instills the Academy’s values on all who pass through her chambers. She is a constant reminder the cost of freedom is immeasurable. Memorial Hall holds the past of the Academy as well as her future not yet realized. She is simply the heart and soul of every Officer that graduates from the United States Naval Academy.