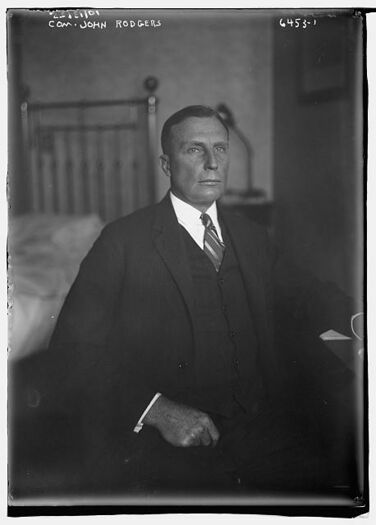

JOHN RODGERS, CDR, USN

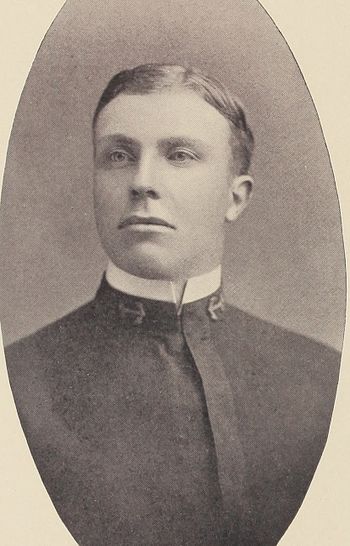

John Rodgers '03

Lucky Bag

From the 1903 Lucky Bag:

JOHN RODGERS

Washington, D.C.

"Jang"

One Stripe (21, 1). Foot-ball team (4, 3, 2, 1). Crew (2, 1), Captain of Crew (1). Hop Committee Class Supper Committee (2). Referee in the Portland Battle Royal. Always unfortunate but never rhinoed—beyond a certain extent. Patentee of a movable tooth, and purloiner of Fidgety Jim's jokes. Can see a joke ten minutes after it is perpetrated. Fumes, but only cigars, and then in conspicuous places with disastrous results. Believes the water at Newport News ideal for swimming, and a suit of oilskins the proper bathing costume. "With his big, red face and his short, white hair, shure and he looks like a turkey gobbler."

JOHN RODGERS

Washington, D.C.

"Jang"

One Stripe (21, 1). Foot-ball team (4, 3, 2, 1). Crew (2, 1), Captain of Crew (1). Hop Committee Class Supper Committee (2). Referee in the Portland Battle Royal. Always unfortunate but never rhinoed—beyond a certain extent. Patentee of a movable tooth, and purloiner of Fidgety Jim's jokes. Can see a joke ten minutes after it is perpetrated. Fumes, but only cigars, and then in conspicuous places with disastrous results. Believes the water at Newport News ideal for swimming, and a suit of oilskins the proper bathing costume. "With his big, red face and his short, white hair, shure and he looks like a turkey gobbler."

Loss

John was lost on August 27, 1926 when the airplane he was piloting crashed into the Delaware River.

Other Information

From researcher Kathy Franz:

John married Ethel R. Grenier on January 13, 1912, at her home in Annapolis. They left for San Diego where he did experimental flights at the aero camp for a few months. Seven months later, on August 17, John quit flying at the request of his wife and took command of the gunboat Yankton. Lt. T. G. Ellyson ('05) took his place in charge of aviation. John and Ethel's daughter Helen Perry was born in Newport, Rhode Island, in July 1913.

In February 1924, John was in charge of two seaplanes which took off from Pearl Harbor and attempted a tour touching three islands – Oahu, Maui and Hawaii. A number of well-known Honolulu businessmen were on the accompanying ship, USS Pelican. Some were even on the flights to generate interest in commercial aviation in the islands.

A short account of John's September 1925 flight to Hawaii was published in the American Legion Monthly of September 1926 (pp 85-86). It was entitled “Via Air and Water.” Pictures of him were on page 16.

Ethel and daughter Helen Perry lived for several years in Tours, France, and returned in 1933 to Washington, D. C. Helen was a debutante that next winter. In July 1937, Helen was an employe of the American Embassy in France. In April 1941, she returned to New York City from Lisbon, Portugal. She married Alain Raoul-Duval, a French officer, in Paris in February 1948. Her mother Ethel died in France in 1955.

John's father John Augustus Rodgers was a Naval Academy graduate, Class of 1868. John's mother was Elizabeth, and his brothers were Alexander and Robert Perry Rodgers. Robert, an architect, was co-designer of the Wright Memorial erected at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. Alexander was born in 1888, and as a young man he lived on a Colorado ranch, went to Mexico and then to Alaska in 1909. He wrote for a while, but then the letters stopped. John took leave from the Navy in the spring of 1910 and followed his path to a hotel in Munson. Alexander had left his diary and other things there, and the family thought he was next going to Fairbanks. In September 1910, they thought they had another lead. His father went looking for him but found nothing.

From Wikipedia:

Rodgers was the great-grandson of Commodores Rodgers and Perry. He was born in Washington, D.C. and graduated from the Naval Academy in 1903. His early naval career included service on ships of various types before studying flying in 1911 and becoming the second American naval officer to fly for the United States Navy. In September 1911, Lieutenant John Rodgers assembled and flew a crated Wright Model B-1 aircraft delivered by Orville Wright at an armory in Annapolis, Maryland, and then bringing naval flight as a pioneer to the United States Navy.

He commanded Division 1, Submarine Force, Atlantic Fleet in 1916; and, after the United States entered World War I, he commanded the Submarine Base at New London, Connecticut.

Following the war, he served in European waters and received the Navy Distinguished Service Medal for outstanding work on minesweeping operations in the North Sea. After several important assignments during the next five years, he commanded Aircraft Squadrons, Battle Fleet, in Langley in 1925.

That year he led the first attempt at a non-stop flight from California to Hawaii. Given the technology of the time, this tested the limits of both aircraft range and the accuracy of aerial navigation. The expedition was to include three planes. Rodgers commanded the flying boat PN-9 No. 1. The PN-9 No. 3 was commanded by Lt. Allen P. Snody. The third plane was to have been a new design, which was not completed in time to join the expedition. Due to the risks, the Navy positioned 10 guard ships spaced 200 miles apart between California and Hawaii to refuel or recover the aircraft if necessary. The two PN-9s departed San Pablo Bay, California (near San Francisco) on August 31. Lt. Snody’s plane had an engine failure about five hours into its flight, was forced to land in the ocean, and was safely recovered.

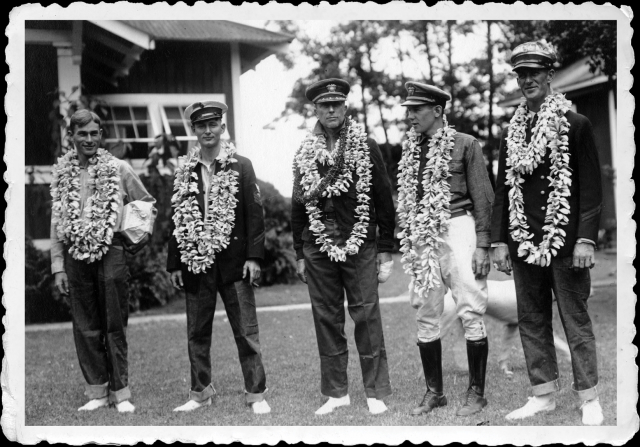

Rodgers’s flight proceeded with few difficulties for more than 1200 miles. However, higher than expected fuel consumption and a weaker than predicted tailwind made it necessary for the plane to land in the ocean and refuel. The plane headed for a refueling ship, but limitations of the navigation technology and erroneous navigation information provided by the ship’s crew caused Rodgers and his crew to miss the ship. The flying boat was forced to land in the ocean when it ran out of fuel on September 1. Since the position of the plane was not known while it was in the air and the plane’s radio could not transmit when the plane was floating on the water, Rodgers and his crew were not found by an extensive, multi-day search by planes and a large number of ships. After passing a night without rescue, Rodgers and his crew used fabric from a wing to make a sail and sailed towards Hawaii, several hundred miles away. Later the plane’s crew used metal flooring to fashion leeboards to improve their ability to steer the flying boat while it was sailing. Finally, nine days later, after sailing the plane 450 miles to within 15 miles of Nawiliwili Bay, Kauai, the plane and its crew were found by submarine USS R-4 under the command of Lt. Donald R. Osborn, Jr, (USNA class of 1920), after a search by the US Navy. They were towed near the reef outside of the port. The harbor master and his daughter rowed out to the plane and helped Rodgers and his crew surf over the reef and into the safety of the harbor. By the time they were found by the submarine, Rodgers and his crew had subsisted a week without food and with limited water. He later shared with a newspaper, "We were taken care of by the good people of the island, who insisted on treating us as invalids, whereas as a matter of fact we were in very good shape and perfectly capable of taking care of ourselves." After their return, Rodgers and his crew were treated as heroes. Also, despite not reaching Hawaii by air, their flight established a new non-stop air distance record for seaplanes of 1992 miles (3206 km).

After this experience, Rodgers served as Assistant Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics until his accidental death in an airplane crash after the plane he was piloting suddenly nose-dived into the Delaware River on August 27, 1926.

He was survived by his ex-wife, from whom he was divorced in 1924, Ethel Greiner Rodgers. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

John was Naval Aviator #2.

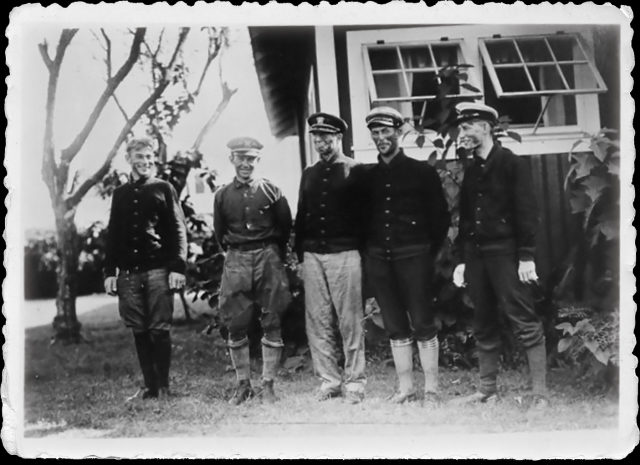

Photographs

Remembrances

From the April 1939 issue of Shipmate:

The Rodgers Flight to Honolulu

An Interview With Lieut. Comdr. B. J. "Smike" Connell, U.S.N. As Told To Victor F. Blakeslee

One of the most romantic chapters in all sea history was carved in the annals of time when Commander John Rodgers and Lieutenant Byron J. Connell with a crew of three attempted the first flight to Honolulu on August 31, 1925. The longest air distance over water between points of land, 2100 nautical miles, is that from the United States to the Hawaiian Islands, and for some time it had been the ambition of every aviator to make this flight.

"We all knew if such a "hop' were successful," Smike said, "airplanes, and especially seaplanes, could fly anywhere. The Pacific and its broad expanse would be conquered. We were delighted, all of us, to be chosen to make this attempt. But before we go any further I want to pay tribute to the memory of our "skipper.' Commander John Rodgers had my deepest affection and respect. I was with him when he died, but he lives on for me and always will as the finest officer and gentleman I have ever served with. The outcome of our flight and our successful sail to one of the Hawaiian Islands was due to his great leadership and to the ability and high morale of the finest enlisted crew ever assembled."

We were sitting in "Smike's" home in the suburbs of Philadelphia. He had kindly consented to give Shipmate an interview and we were quick to take advantage of his offer by appearing almost immediately at his front door. Commander Connell, who was chosen by Commander Rodgers to pilot his plane is now on duty as Planning Superintendent at the Naval Aircraft Factory, Philadelphia. He would still rather sit in a cockpit than eat, and is one of the Navy's most famous aviators. We looked up his record in the Navy Department and found that during his outstanding career in 1925, 1926 and 1927 he established 8 world's and 19 American seaplane records for distance, duration, speed and altitude. To list them all would fill several pages. In listening to "Smike" we realized we were hearing the joys, sorrows, setbacks and triumphs of airplane history unfold themselves,—from a man who had experienced one of the most harrowing adventures of all time.

For nine days the entire world listened on the radio, rushed for the latest editions and called up their local newspapers to find out if the P-N-9-1 had been rescued. For on August 31, 1925 this "ship" had started for Honolulu, the first to ever attempt this longest span over water, and through lack of fuel had been forced down approximately 350 miles from its goal. With very little food and hardly any water five weakened men actually rigged up sails using fabric cut from the wings and steered for the beach while a school of sharks kept watch over them day and night waiting for the break up. Courage, determination, heroism. If any of their little band had lacked these attributes they never could have saved themselves. But they did. To tell their story was not the desire of this interviewer. "Smike" was sitting before us and had consented to tell it himself.

"The morning before leaving San Francisco after three months difficult preparatory work we had our dress rehearsal, checking up on the motors, going over every detail. Then the final day arrived. Admiral Moffett, Captain Moses and Colonel Lahm made a last minute trip to our 'ocean home' by speed boat, to wish us good luck. Captain Rodgers then gave the signal to start the engines. My first impulse was to cuss a little when for some reason or other the port engine didn't start immediately. In a few minutes, however, it began to purr and I heaved a sigh of relief. We could now warm them both up.

"We had counted on a 15-mile wind to aid us in our takeoff. But what little breeze there was seemed to be dying down. With our enormous load of gas, 1350 gallons, this worried me. If we could only get off with our total load of approximately 19500 pounds the rest would be easy. I taxied into position and opened up the throttles. But after failing to get off,—we had run about a mile,—I closed them to prevent overheating the engines and taxied back to shallower water for another try. 'I'll get this plane off or sink it,' I muttered to myself as I opened the throttles wide again and worked the controls until I was nearly exhausted. Finally I felt her gradually begin to climb up on the step and wanted to shout 'hurrah!' to all hands, although the roar of the motors made conversation impossible. After a six mile run I was able to pull her off the water. The flight had begun. I was able to gain an altitude of only 300 feet as we approached the Golden Gate, due to our heavy load. Photographic planes hovered around us, but I didn't think of anything except flying the ship—not until I could get through that Gate anyhow. We knew we had just sufficient gas to make it with favorable winds, almost a certainty at that time of the year. The engines were humming 'Honolulu' to me and I was determined nothing should stop us. Captain Rodgers was already busy in the bow checking the drift and as soon as we were clear of the Golden Gate he passed back a note with the course and I checked all three compasses."

There were station ships all along the route, the William Jones, McCawley, Corry, Myer, Doyen, Langley, Reno, Farragut, Aroostook, and Tanager being spread out along the course 200 miles apart.

"We began to pick up station ship after station ship right on the line and I was able to relax a little. The sun finally went down and night approached. Now we should pick up that following wind. We did, but the velocity was very light—much lighter than we had hoped for. If it would only pick up to 15 or 20 miles an hour! But it didn't. The night, however, was beautiful. The moon was full, we could see the water, and we were having no trouble in picking up our station ships. During the night the Captain threw over flares which lighted when they struck the water and by these he estimated our drift. This together with star sights and radio compass bearings furnished by the station ships (we had no means of taking such bearings ourselves) kept us right on the course. The engines were operating perfectly.

"We were supposed to eat two sandwiches and drink a cup of coffee every six hours—doctor's orders. But most of us were too busy to eat. The coffee, however, tasted very good and I drank some black.

"Toward morning we were more than half way across, the moon had disappeared and we hit a rain squall. It is true that it's always darkest just before dawn. I was beginning to get a little tired, especially my eyes, from keeping them riveted on the compass. When the sun rose I noticed there was hardly a breath of air stirring and there had been little or no favorable wind during the night. Tough luck. We checked our gasoline and I started to do some worrying. For the first time I realized we weren't going to make it without landing and refueling from one of the station ships.

"I had been in the pilot's cockpit nearly 22 hours now and I confess I was very tired. My back especially ached from the vibration of long sitting on a hard metal seat with only a thin cushion under me.

"It was apparent that we would have to land soon as we estimated there was only enough gasoline left for 3 ½ flying hours. Messages were shooting back and forth to the station ships and it was decided we would land and refuel from the Aroostook. A message was sent giving this information. We had sufficient gasoline to reach the Aroostook with an hour's leeway. I was sure we'd pick her up without difficulty. We hadn't missed a station ship yet and Captain Rodgers was one of the most expert aerial navigators in the Navy.

"The Captain was working the chart board overtime and we finally reached the position where we expected the Aroostook would be. But we did not sight the ship. During the run towards the ship the Captain had plotted a number of radio compass bearings furnished by the Aroostook (I repeat we had no means of taking radio compass bearings from our plane) and now we asked for more bearings. Since the increased run of the bearings indicated that the ship was north of us, the Captain set the course north and we attempted to locate her. The visibility became poor and we encountered intermittent rain squalls. We continued to search for the Aroostook until our gasoline supply was exhausted.

"We were light now, of course, and the sea did not look rough from our altitude as we started down. I spiralled into the wind and began my glide for a landing from 800 feet. The radioman continued to send position reports all the way down. I leveled off and made a full stall landing. I guess it was a lucky one because we settled on without leaving the water in a ten foot sea and very little wind—rather unfavorable conditions. It was 1615 by my watch which made our duration of flight 25 hours and 23 minutes. We still expected to be quickly located, and given the few hundred gallons of gasoline necessary for us to fly the remaining distance to Honolulu.

"There was very little said after landing. Everybody was tired and disgusted. We merely looked at each other. For three months we had worked night and day to make a nonstop flight. No one, I guess, had the heart to say anything. Captain Rodgers took some sights to check our position (later that evening he got some more and his D. R. position checked closely with his position by observation. I crawled back between the wings, lay on top of the hull and went to sleep. When I awoke 4 or 5 hours later it was dark. I ate about half a sandwich and threw the rest into the hull. A few days later I hunted diligently for that other half.

"I found everybody awake and we discussed the fact that if the sea calmed during the night and if the Aroostook showed up bright and early in the morning to give us gasoline (which we fully expected) we would be in Honolulu in a short time. We turned on the light on the top wing so we could be seen easily by any of the searching ships, arranged the watch (the Captain stood the first one) and put out a bucket for a sea anchor to hold us up to the wind. Then all of us slept like tops except the man on watch.

"In the morning I was stiff from sleeping on the hard top of a metal hull and I noticed the Captain who had spent the night cramped up in the front cockpit, was trying to get the crimps out of his legs. Only one of our crew was sick. It was just ordinary seasickness, but he certainly made up for the rest of us.

"The Captain took some more sights and estimated our drift at two miles an hour during the night. My breakfast consisted of a little water, the sandwiches being mouldy already. The skipper had brought along some poi in a thermos jar, but this was also spoiled. So he joined me in water for breakfast. We sat around talking, expecting to be picked up. But the day came to its long end and we had seen nothing. The waves were causing some damage to the lower wings outboard of the struts. We hated to cut away the fabric as we wanted to be able to fly on in if found, but we ultimately had to do it to increase the seaworthiness of our craft. Our radio kite carried away and we rigged up a temporary antenna. We could now receive messages from a distance of four or five hundred miles, but could not send, having no power. It was interesting to hear the news of the world including items about ourselves, and follow the work of the searching vessels. We plotted all their positions and saw they were searching too far to the south of us. They had estimated our drift at 5 knots and by simple arithmetic they weren't going to get any closer. The Captain then cheered everyone up by saying: 'Many people spend a lot of money to go yachting with more discomforts than we have.' Later our radio was to bring us news of the Shenandoah disaster.

"A message from the Aroostook told us to fire star shells if we saw them. We were still hopeful of being picked up as another night rolled around. So far none of us had had anything but water and a few crackers since landing. I was always tempted to take deep gulps of our meager water supply, but merely wetted my lips instead. Hunger began to grow less. You can live a long time without food and you even get so you don't miss it after a day or two, but you can't live very long without water and we very carefully husbanded the little we had.

"The following morning we were awakened by a cry from the man on watch: 'Smoke! Smoke!' Sure enough there was a merchant steamer heading right toward us, it seemed. I crawled out on the wing and cut loose one of the wing tip flares, then climbed up on the top wing and set it off to attract her attention. One of the men waved a piece of fabric tied on a stick until exhausted. We also made a fire in a bucket and smudged it with oil and set off Very star shells. Weakness from our efforts was fast overcoming all of us. Besides I was thinking of a good square meal aboard that ship. She didn't see us. She passed within 5 miles of us. Afterwards I realized we were between her and the sun which was low on the horizon and which probably prevented her from sighting us.

"This waiting to be picked up was beginning to be monotonous. We had 7 canteens of water and 5 sandwiches left, a few crackers and a six pound can of corned beef. I took the waxed paper off the sandwiches and they were mouldy. So I toasted them "on deck' in the hot sun. Each man then wrote his name on his water canteen. The two extra ones were held in safekeeping by the Captain.

"By the third day we had lost all hope of being picked up and carefully cut off all the fabric from both lower wings. We rigged up sails. The plane, we felt, would not break up unless we hit a real storm. We fastened our sails to the flying wires with safety wire, thus increasing our "speed' toward Oahu. We also tried to rig up a radio sending set and worked all day on it. We finally made a spark set and sent out a number of position reports, but the set lacked range and none of our messages was received.

"Our crackers were exhausted on the third day, but the monotony was broken on the morning of the fourth day by Pope, our assistant pilot. He looked over the side and said: "Good morning, strangers.' We looked also and there were a couple of nice playmates watching us—tiger sharks. They were about 15 feet long. From then on a school of them followed us continuously. We never so appreciated a strong duraluminum hull as we did ours now. If we just could keep from cracking up! Fortunately so far the hull was standing up beautifully.

"That night we opened up the canned willy and all of us were ghastly ill from eating such salty food without sufficient water. The Captain alone did not partake and came off clear. Then our cigarettes ran out. We would have given anything for a good smoke. One of the men had a few cigars and the crew all took turns taking a puff on them until they too were gone. When a cigar was 'not in use' they fastened it to a motor with a safety wire to prevent loss of the butt.

"One night when it got very rough we took down the sails and put out our sea anchor again. The wing tips took a terrible beating. We kept a man continuously in the pilot seat at the controls to keep the ship on its course, and to ease the force of the waves on the wing tip pontoons by using the ailerons.

"Sailing a plane in the water requires considerable skill. All through this stormy night everyone of us would wake up when a heavy wave hit us, wondering if our lower wings had carried away. Next day we lashed the spars in the lower wings where they had begun to buckle.

"Saturday night we were awakened by the Captain's cry of 'Rain! Rain!' We leaped to our feet and spread our 'sail' over the forward part of the hull. It sprinkled only for a few minutes and our sail was barely moistened. We all got down on all fours and licked the fabric with our tongues. The skipper seemed to enjoy this immensely.

"The next day I noticed the Captain crawling on his hands and knees down in the bilges. He was looking for a piece of crust someone had dropped there days before. He finally found it. It was about as big as the end of your thumb. That night a flying fish about the size of a minnow flew into the cockpit. The Captain found it and stroked it tenderly. We rigged up a light hoping to catch some more. But the Captain made our only "haul." He insisted on sharing it, but we finally ragged him into eating it himself, head, wings and tail, all in one swallow. He fully enjoyed it.

"Our water supply was getting low. So we rigged up a still which the Captain's mother, one of the loveliest women I have ever met, had given him before leaving. We ran the still for five hours but were able to distill less than a quart of fresh water. As our supply of wood, taken from the trailing edges of the lower wings and placed in a bucket to produce a fire, was soon exhausted, we couldn't depend longer on that. But the little water we did distill tasted wonderful. A message to the Captain during these efforts from the Aroostook read: 'Cheer up, John, we'll get you yet. Hammer on the keel so the submarines can hear you.' . . . Two of the men grabbed hammers and began to pound on the hull, but we had to calm them down lest they drive a hole through the bottom.

"We all began to get weaker and weaker. Every movement became a great effort. Soon we would have to lie down after any great exertion. It took a terrific effort to man the controls and hold a compass course. Then we got to the stage when we could only crawl. The two reserve canteens of water now went on issue, taste by taste,—and finally they too were exhausted. The Captain offered his last sip to one of the crew who was in particularly bad shape. It was just a question of how long we could last. We knew we had sailed 300 miles, or about 50 miles a day and our course was putting us slowly nearer to the island of Oahu.

"Tuesday night we saw the Army searchlights at Schofield Barracks, Oahu: our first contact with life other than our own since seeing the steamer that had passed us five days previously.

"'How far away are those lights, Captain?' one of the men asked.

"'Only about a hundred miles,' he replied.

"Then we intercepted messages saying we had been given up for lost. They indicated the search might be abandoned. But we were now too weak to listen in much on our radio.

"Something had to be done to sail the plane to land. Our position was such that the Northeast trade winds would take us through the middle of the channel between Oahu and Kauai without touching shore. It occurred to me that if we could rig up a keel, it would help us to make good a course more off the wind. Perhaps then we could tack enough to hit the beach. So we used the floor boards, lashing them alongside the hull. We then set our course for Oahu, putting on all sail possible. The next morning we could see the island as plain as day. It was a wonderful sight, but it was 50 miles away. With our keel we were able to tack 15 degrees off the wind; and were making the terrific speed of 3 knots.

"When it became apparent we could not make Oahu, the Captain decided to set our course for the island of Kauai. .. If we had gone on towards Oahu and missed it we had the whole broad Pacific ahead of us. It was pretty tough losing sight of that land, only 50 miles away, and head for Kauai, a hundred miles distant. We all of us looked longingly ashore. We felt we had lost our last friend.

"Our despair turned to cheer when we settled down again and saw a black cloud ahead of us. We made all preparations again to catch any rain that might fall. At about noon it poured and kept on pouring, for a half hour. It saved our lives. Our "caught water' was full of aluminum paint from our fabric sail, but it was the drink of a lifetime. We collected three whole quarts besides all we could drink.

"Thursday morning we found Kauai just ahead of us. The Captain's navigation had been perfect. By two o'clock we were only ten miles off shore and all our worries were over. It was a great feeling. We built a fire in a bucket and fired Very shells to attract the attention of anyone on the beach. If not sighted we felt we could sail the plane into the harbor of Abukini as we were directly to windward. Fifteen minutes later one of the men looked to seaward and yelled: 'There's a 'sub,' right behind us.' It was the R-4.

"'What plane?' the R-4 semaphored.

"'P-N-9-1 from San Francisco,' the radioman semaphored back.

"We asked for water, food, coffee—and cigarettes. The water, though fresh, could not hold a candle to our "aluminumdope' product. But since our rain we were no longer very thirsty. The R-4 threw us a line and towed us toward the beach. We looked like Robinson Crusoes after our nine days sail with long beards and dirty faces. As the R-4 towed us in the Captain remarked: 'Well, we're the first plane to reach the Hawaiian Islands even though we did have to sail the last 450 miles!' Some of the crew suggested that we should sail the last 10 miles too and the Captain said jokingly: "Every ship takes on a pilot going into port!'"

Epilogue

Less than a year later Captain John Rodgers, then Assistant Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics, flew to Philadelphia from Washington to consult with Commander Connell about another flight they were contemplating. This time they had hoped to be the first to span the Pacific. In landing at the flying field at the Philadelphia Navy Yard the plane went into a tail spin and crashed into the river a short distance from shore. "Smike" Connell was the first to rush out and reach his old skipper's side. Rodgers was mortally injured. These two intrepid airmen had their last words together there, for Captain Rodgers died a few hours later. One of his last spoken thoughts was to inquire about the welfare of the crew that was with him on the P-N-9-1. The irony of fate is sometimes beyond belief. But at least these gallant officers were together at the great Captain's end.

There was another article on this voyage in the February 2019 issue of Naval History Magazine.

The "Register of Commissioned and Warrant Officers of the United States Navy and Marine Corps" was published annually from 1815 through at least the 1970s; it provided rank, command or station, and occasionally billet until the beginning of World War II when command/station was no longer included. Scanned copies were reviewed and data entered from the mid-1840s through 1922, when more-frequent Navy Directories were available.

The Navy Directory was a publication that provided information on the command, billet, and rank of every active and retired naval officer. Single editions have been found online from January 1915 and March 1918, and then from three to six editions per year from 1923 through 1940; the final edition is from April 1941.

The entries in both series of documents are sometimes cryptic and confusing. They are often inconsistent, even within an edition, with the name of commands; this is especially true for aviation squadrons in the 1920s and early 1930s.

Alumni listed at the same command may or may not have had significant interactions; they could have shared a stateroom or workspace, stood many hours of watch together, or, especially at the larger commands, they might not have known each other at all. The information provides the opportunity to draw connections that are otherwise invisible, though, and gives a fuller view of the professional experiences of these alumni in Memorial Hall.

January 1905

July 1906

January 1908

January 1909

January 1910

January 1911

January 1912

January 1914

January 1915

January 1916

January 1917

March 1918

January 1919

January 1920

January 1921

January 1922

May 1923

July 1923

September 1923

November 1923

January 1924

March 1924

May 1924

July 1924

September 1924

November 1924

January 1925

March 1925

May 1925

July 1925

October 1925

January 1926

Memorial

John's classmates erected a plaque in his honor in Memorial Hall. It reads in part, "He dedicated his life to the advancement of aviation and met his death in an airplane accident. His courage, fortitude, and leadership during the first flight attempted across the Pacific to the Hawaiian Islands made him a hero in the eyes of the world and reflected glory upon the Naval Service. This tablet is erected by his classmates of 1908 as a token of their love and esteem."

From the United States Naval Academy Facebook page on September 10, 2019:

Did you know the U.S. Naval Academy is the birthplace of the U.S. Naval Air Forces? On Friday, we celebrated the dedication of the plaque outside of Dahlgren Hall!

On September 7, 1911, Lieutenant John Rodgers, USNA Class of 1903, took off from the Naval Academy in a Wright B-1 aircraft. With less than 450 feet to become airborne, an eager group of midshipmen assisted by running alongside while pulling ropes wrapped around the wing struts. Rodgers circled the Naval Academy, made several low passes, and landed. For the first time in history, a aircraft owned by the Navy and piloted by a Naval Aviator flew from naval property.

A replica of the Wright B-1 is displayed in Dahlgren Hall.

Namesakes

USS John Rodgers (DD 574) was named for him, his uncle, and his grandfather; the ship was sponsored by his daughter, Helen. USS John Rodgers (DD 983) was also named for the three John Rodgers.

John Rodgers Field—now Kalaeloa Airport, Hawaii—was named for him.

John is one of 4 members of the Class of 1903 on Virtual Memorial Hall.

The "category" links below lead to lists of related Honorees; use them to explore further the service and sacrifice of alumni in Memorial Hall.