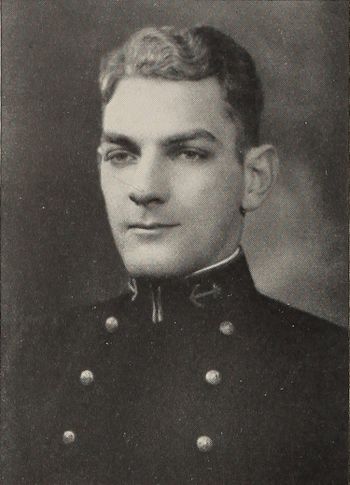

FRANCIS H. WILLIAMS, LTCOL, USMC

Francis Williams '30

Lucky Bag

From the 1930 Lucky Bag:

FRANCIS HUBERT WILLIAMS

Colorado Springs, Colorado

"Hube" "Joe" "Bill"

"AND in this corner, gentlemen, we have Hub Williams"—This would be, perhaps, as fitting as possible an introduction for Joe, for he has fought his way through life continuously. He's a fighter at heart!

The entrance examination battle over, Joe made a name for himself during Plebe summer by winning the 135-lb. company championship. From then, his rise has been steady and continuous. As captain of the Plebe boxing team, further laurels were his from which he derived no small amount of pride.

Achievement upon achievement, honor upon honor, these have been the lot of Joe, to come to a crescendo when he fought his way to the intercollegiate boxing championship crown. In the words of "Spike Webb"—a real champ!"

Joe's philosophy of life has embraced the desire to attain knowledge rather than grades—to know, not merely to be known to know. Literature, as distinct from "reading," has been his chief avocation.

They are making a Marine of him. And whether in Nicaragua, Pago Pago, or "on the far China Station," that organization of fighters has added to its roll—a fighter.

Boxing 4, 3, 2, 1; Intercollegiate Champion 3; M.P.O.

FRANCIS HUBERT WILLIAMS

Colorado Springs, Colorado

"Hube" "Joe" "Bill"

"AND in this corner, gentlemen, we have Hub Williams"—This would be, perhaps, as fitting as possible an introduction for Joe, for he has fought his way through life continuously. He's a fighter at heart!

The entrance examination battle over, Joe made a name for himself during Plebe summer by winning the 135-lb. company championship. From then, his rise has been steady and continuous. As captain of the Plebe boxing team, further laurels were his from which he derived no small amount of pride.

Achievement upon achievement, honor upon honor, these have been the lot of Joe, to come to a crescendo when he fought his way to the intercollegiate boxing championship crown. In the words of "Spike Webb"—a real champ!"

Joe's philosophy of life has embraced the desire to attain knowledge rather than grades—to know, not merely to be known to know. Literature, as distinct from "reading," has been his chief avocation.

They are making a Marine of him. And whether in Nicaragua, Pago Pago, or "on the far China Station," that organization of fighters has added to its roll—a fighter.

Boxing 4, 3, 2, 1; Intercollegiate Champion 3; M.P.O.

Loss

Francis was lost on March 6, 1945, when he died while in a Japanese Prisoner of War camp.

Other Information

From researcher Kathy Franz:

Francis was born in Tampa, Florida.

He married A. Florence Westenhagen on June 5, 1930, at the Naval Academy Chapel. Robert Lee Moore, Jr., (’30) was his best man. In 1940, the family lived in Washington, D. C. Their son Robert was 6, and daughter Marsha was 3.

His parents were Frank and Corinne (Blair) Williams. He had a brother James. James’ first wife died in Colorado around 1924, and he married Margaret Evans in 1927 in Philadelphia. By then, their father Frank had died.

His wife was listed as next of kin. Francis is buried in the Manila American Cemetery and Memorial.

Photographs

Wartime Service

From Zamboanga.com:

On December 26, 1941, while Japanese troops occupied Manila and fought American and Filipino forces on Bataan, Marine Capt Francis H. Williams and a detail of leathernecks set demolition charges on anything of value at the naval base. They blew the base, as it was then, into oblivion. They left Olongapo in flaming ruins and headed for the last bastion of American resistance on the Manila Harbor island of Corregidor.

From Naval History and Heritage Command:

Using charges improvised from 300-pound mines, "Williams set out with his demolition gang to do a good job of erasing the Naval Station from the face of the globe." They sank the hull of the old armored cruiser Rochester in the bay and blew up or burned everything of value except the barracks which closely bordered the native town.45 The last supplies were loaded early Christmas evening, and the rear echelon pulled out with darkness.

From Corregidor.com:

Life on a Bull's Eye

During the 27 days between the fall of Bataan and the assault on Corregidor, life on The Rock became a living hell. The men in the open gun pits and exposed beach defenses were subjected to an increasing rain of shells and bombs. It became virtually impossible to move about the island by daylight; enemy artillery spotters aloft in observation balloons on Bataan and in planes overhead had a clear view of their targets. The dense vegetation which had once covered most of Corregidor was stripped away by blast and fragmentation to reveal the dispositions of Howard's command. The tunnels through Malinta Hill, their laterals crowded with headquarters installations and hospital beds, offered refuge for only a fraction of the 11,000-man garrison and the rest of the defenders had to stick it out with little hope of protection from the deadly downpour.

Most of the escapees from Bataan were ordered to join the 4th Marines, thus adding 72 officers and 1,173 enlisted men to its strength between 9 and 12 April. The majority of the Army combat veterans, however, "were in such poor physical condition that they were incapable of even light work," and had to be hospitalized. The mixed collection of infantry, artillery, aviation, and service personnel from both American and Philippine units assigned to the beach defense battalions was in little better shape than the men who had been committed to the hospital under Malinta Hill. The commander of 1/4's reserve, First Lieutenant Robert F. Jenkins, Jr., who received a typical contingent of Bataan men to augment his small force commented that he:

... had never seen men in such poor physical condition. Their clothing was ragged and stained from perspiration and dirt. Their gaunt, unshaven faces were strained and emaciated. Some of them were already suffering from beri-beri as a result of a starvation diet of rice for weeks. We did what we could for them and then put them to work on the beach defenses.

The sailors from Mariveles, mostly crewmen from the now-scuttled Canopus, were kept together and formed into a new 275-man reserve battalion for the regiment, the 4th Battalion, 4th Marines. Not only was the designation of 4/4 unusual, but so was its makeup and its personnel. Only six Marines served in the battalion: its commander, Major Francis H. Williams, and five NCOs. The staff, company commanders, and platoon leaders were drawn from the nine Army and 18 Navy officers assigned to assist Williams. The four rifle companies were designated Q, R, S, and T, the highest lettered companies the men had ever heard of. Another boast of the bluejackets turned Marines was that they were "the highest paid battalion in the world, as most of the men were petty officers of the upper pay grades."

The new organization went into bivouac in Government Ravine as part of the regimental reserve. The reserve had heretofore consisted of men from the Headquarters and Service Companies, reinforced by Philippine Air cadets and Marines from Bataan. Major Max W. Schaeffer, who had replaced Major King as reserve commander, had organized this force of approximately 250 men into two tactical companies, O and P. Company O was commanded by Captain Robert Chambers, Jr. and Company P by Lieutenant Hogaboom; the platoons were led by Marine warrant officers and senior NCOs.

A good part of Schaeffer's men had primary duties connected with regimental supply and administration, but each afternoon the companies assembled in the bivouac area where the troops were instructed in basic infantry tactics and the employment of their weapons. Despite the constant interruptions of air raids and shellings, the Marines and Filipinos had a chance "to get acquainted with each other, familiarize themselves with each others' voices, and to learn [the] teamwork" so essential to effective combat operations. Frequently, Major Schaeffer conducted his company and platoon commanders on reconnaissance of beach defenses so that the reserve leaders would be familiar with routes of approach and terrain in each sector in which they might fight.

While Schaeffer's unit had had some time to train before the Japanese stepped up their bombardment of the island in late March, Williams' battalion was organized at the inception of the period of heaviest enemy fire and spent part of every day huddled in foxholes dug along the trail between Geary Point and Government Ravine. Any let-up in the bombardment would be the signal for small groups of men to gather around the Army officers and Marine NCOs for instruction in the use of their weapons and the tactics of small units. Rifles were zeroed in on floating debris in the bay and for most of the men this marksmanship training was their first since Navy boot camp. When darkness limited Japanese shelling to harassment and interdiction fires, the sailors formed eager audiences for the Army Bataan veterans who gave them a resumé of enemy battle tactics. Every man was dead serious, knowing that his chances for survival depended to a large extent upon how much he learned. "The chips were down; there was no horseplay."

To a very great extent the record of the 4th Battalion in the fighting on Corregidor was a tribute to the inspirational leadership of its commander. During the trying period under enemy shellfire and bombing when the battalion's character was molded, Major Williams seemed to be omnipresent; wherever the bombardment was heaviest, he showed up to see how his men were weathering the storm. When on separate occasions Battery Crockett and then Battery Geary were hit and set afire, he led rescue parties from 4/4 into the resulting holocausts of flame, choking smoke, and exploding ammunition to rescue the wounded. He seemed to have an utter disregard for his own safety in the face of any need for his presence. Survivors of his battalion agree with startling unanimity that he was a giant among men at a time when courage was commonplace.

Raw courage was a necessity on the fortified islands after Bataan's fall, since there was no defiladed position that could not be reached by Japanese 240mm howitzers firing from Cavite and Bataan. The bombers overhead, increasingly bold as gun after gun of the antiaircraft defenses was knocked out, came down lower to pinpoint targets. Counterbattery and antiaircraft fire silenced some enemy guns and accounted for a number of planes, but nothing seemed to halt the buildup of preparatory fires.

On 28 April Howard issued a warning to his battalions that the next day would be a rough one. It was the Emperor's birthday and the Japanese could be expected to "celebrate by unusual aerial and artillery bombardment." The colonel's prophecy proved to be a true one, and on the 29th one observer noted that even "the kitchen sink came over." The birthday celebration marked the beginning of a period when the enemy bombarded the island without letup, day and night. The men manning the beach defenses of Corregidor's East Sector found it:

... practically impossible to get any rest or to repair any damage to our positions and barbed wire. Our field telephone system was knocked out; our water supply was ruined (drinking water had to be hauled from the other end of the island in large powder cans) ... Corregidor was enveloped in a cloud of smoke, dust, and the continuous roar of bursting shells and bombs. There were many more casualties than we had suffered in the previous five months.

About three days prior to the Japanese landing, Lieutenant Colonel Beecher reported to Colonel Howard that defensive installations in the 1st Battalion's sector were:

... practically destroyed. Very little defensive wire remained, tank traps constructed with great difficulty had been rendered useless, and all my weapons were in temporary emplacements as the original emplacements had been destroyed. I told Colonel Howard at this time that I was very dubious as to my ability to withstand a landing attack in force. Colonel Howard reported the facts to General Wainwright, who, according to Colonel Howard, said that he would never surrender. I pointed out to Colonel Howard that I had said nothing about surrender but that I was merely reporting the facts as it was my duty to do.

The increase in the fury of the Japanese bombardment with the coming of May, coupled with the frequent sightings of landing craft along the eastern shore of Bataan, clearly pointed to the imminence of an enemy landing attempt. The last successful effort to evacuate personnel from the island forts was made on the night of 3 May. The submarine Spearfish surfaced after dark outside the mine fields off Corregidor and took on a party of officers and nurses who had been ordered out, as well as a load of important USFIP records and a roster of every person still alive on the islands. The 4th Marines sent out their regimental journal, its last entry, dated 2 May, the list of the five men who had been killed and the nine who had been wounded during the day's bombardment.

To one of the lucky few who got orders to leave on the Spearfish the receding island looked "beaten and burnt to a crisp." In one day, 2 May, USFIP estimated that 12 240mm shells a minute had fallen on Corregidor during a five-hour period. On the same day the Japanese flew 55 sorties over the islands dropping 12 1,000 pound, 45 500-pound, and 159 200-pound bombs. The damage was extensive. Battery Geary's eight 12-inch mortars were completely destroyed as was one of Battery Crockett's two 12-inch guns. The enemy fire also knocked out of action two more 12-inch mortars, a 3-inch gun, three searchlights, five 3-inch and three .50 caliber antiaircraft guns, and a height finder. Data transmission cables to the guns were cut in many places and all communication lines were damaged. The beach defenses lost four machine guns, a 37mm, and a pillbox; barbed wire, mine fields, and antiboat obstacles were torn apart.

The logical landing points for an assault against Corregidor, the entire East Sector and the ravines that gave access to Topside and Middleside, received a special working over so steady and deadly that the effectiveness of the beach defenses was sharply reduced. Casualties mounted as the men's foxholes, trenches, and shelters crumbled under the fire. Unit leaders checking the state of the defenses were especially vulnerable to the fragments of steel which swept the ground bare. By the Japanese-appointed X-Day (5 May) the 1st Battalion had lost the commander of Company A, Major Harry C. Lang, and Captain Paul A. Brown, commanding Company B, had been hospitalized as a result of severe concussion suffered during an enemy bombing attack. Three Army officers attached to the Reserve Company, an officer of Company B, and another of Company D had all been severely wounded.

Despite the damage to defenses it had so laboriously constructed, the 4th Marines was ready, indeed almost eager, to meet a Japanese assault after days and weeks of absorbing punishment without a chance to strike back. On the eve of a battle which no one doubted was coming, the regiment was perhaps the most unusual Marine unit ever to take the field. From an understrength two-battalion regiment of less than 800 Marine regulars it had grown until it mustered almost 4,000 officers and men drawn from all the services and 142 different organizations. Its ranks contained 72 Marine officers and 1,368 enlisted Marines, 37 Navy officers and 848 bluejackets, and 111 American and Philippine Air Corps, Army, Scout, and Constabulary officers with 1,455 of their men.

The units that actually met the Japanese at the beaches--1/4, 4/4, and the regimental reserve--had such a varied makeup that it deserves to be recorded:

Service Componeent HQ Co Service Co 1st Bn 4th Bn Off Enl Off Enl Off Enl Off Enl USMC & USMCR 14 80 6 63 16 344 1 5 USN (MC & DC) 3 7 1 3 13 2 6 USN 1 16 1 1 78 16 262 USNR 21 30 USA 1 1 26 286 9 2 Philippine Navy 4 Philippine Army Air 6 83 7 217 Philippine Scouts 33 Philippine Army 22 Philippine Constabulary 1 1 Total 25 211 7 65 53 1,024 28 275 The Japanese Landing

The area chosen by the Japanese for their initial assault, the 4th Marines' East Sector, was a shambles by nightfall on 5 May. Two days earlier the regimental intelligence journal had noted that:

There has been a distinct shifting of enemy artillery fire from inland targets to our beach defenses on the north side of Corregidor the past 24 hours.

This concentration of fire continued and intensified, smashing the last vestiges of a coordinated and cohesive defensive zone and shaping 1/4's beach positions into an irregular series of strong points where a few machine guns and 37mm's were still in firing order. A pair of Philippine Scout-manned 75mm guns, located just east of North Point, which had never revealed their position, also escaped the destructive fires. Wire lines to command posts were ripped apart and could not be repaired; "command could be exercised and intelligence obtained only by use of foot messengers, which medium was uncertain under the heavy and continuous artillery and air bombardment."

Along the northern side of the hogback ridge that traced its course from Malinta Hill to the bend in Corregidor's tail, Company A and the reserves of 1/4 waited doggedly for the Japanese to come. There was no sharp division between unit defense sectors, and the men of the various units intermingled as the bombardment demolished prepared positions. Along the battered base and sides of Malinta Hill, a special target for enemy fire, were the men of Lieutenant Jenkins' Reserve Company. Next to them, holding the shoreline up to Infantry point, was a rifle platoon organized from 1/4's Headquarters Company; Captain Lewis H. Pickup, the company commander, held concurrent command of Company A, having taken over on the death of Major Lang. The 1st Platoon under First Lieutenant William F. Harris defended the beaches from Infantry to Cavalry Points, the landing site selected in Japanese pre-assault plans. Master Gunnery Sergeant John Mercurio's 2d Platoon's positions rimmed the gentle curve of land from Cavalry to North Point. Extending from North Point to the tip of the island's tail were the foxholes and machine-gun emplacements of First Sergeant Noble W. Well's 3d Platoon.

Positions along the top of the steep southern face of the East Sector's dominant ridge were occupied by the platoons of Company B under First Lieutenant Alan S. Manning, who had taken over when Captain Brown was wounded. The machine guns and 37mm's of Captain Noel O. Castle's Company D were emplaced in commanding positions along the beaches on both sides of the island; the company's mortars were in firing positions near Malinta Hill.

At about 2100 of 5 May, sensitive sound locators on Corregidor picked up the noise of many barges warming up their motors near Limay on Bataan's east coast. Warning of an impending landing was flashed to responsible higher headquarters, but the lack of wire communication kept the word from reaching the men in the foxholes along the beaches of the East Sector. They did not need any additional advice of enemy intentions anyway, since the whole regiment had been on an all-out alert every night for a month, momentarily expecting Japanese landing barges to loom out of the darkness. The men of 1/4 had withstood some pretty stiff shellings, too, and they waited, but nothing to compare with the barrage that began falling on the beach defenses manned by Harris' 1st Platoon at about 2245.

The Japanese had begun to deliver the short preparatory bombardment designed to cover the approach of Colonel Sato's assault waves which was called for in their operation plan. If Sato's boat groups adhered to their schedule they would rendezvous and head in for the beaches just as the artillery fire lifted and shifted to the west, walling off the landing area from American reinforcement efforts. The regiment would be ashore before the moon rose near midnight to give Corregidor's gunners a clear target. In two respects the plan miscarried, and for a while it was touch and go for the assault troops.

The artillery shoot went off on schedule, but Sato's first waves, transporting most of his 1st Battalion, were carried by an unexpectedly strong incoming tide hundreds of yards to the east of the designated landing beaches. Guides in the oncoming craft were unable to recognize landmarks in the darkness, and from water level the tail of the island looked markedly uniform as smoke and dust raised by the shelling obscured the shoreline. The 61st Regiment's 2d Battalion, slated to follow close on the heels of the 1st, was delayed and disrupted by faulty boat handling and tide currents until it came in well out of position and under the full light of the moon.

When the Japanese preparatory fires lifted shortly after 2300, the troops along the East Sector beaches spotted the scattered landing craft of the 1st Battalion, 61st heading in for the beaches at North Point. The few remaining searchlights illuminated the barges, and the island's tail erupted with fire. Enemy artillery knocked out the searchlights almost as soon as they showed themselves; but it made little difference, since streams of tracer bullets from beach defense machine guns furnished enough light for the Scout 75's near North Point and 1/4's 37's to find targets. A Japanese observer on Bataan described the resulting scene as "sheer massacre," but the enemy 1st Battalion came in close enough behind its preparation to get a good portion of its men ashore. Although the Japanese infantrymen overwhelmed Mercurio's 2d Platoon, the fighting was fierce and the enemy casualties in the water and on the beach were heavy. Colonel Sato, who landed with the first waves, sorely needed his 2d Battalion's strength.

This straggling battalion which began heading shoreward about midnight suffered much more damage than the first waves. The remaining coast defense guns and mortars on Corregidor, backed up by the fire of Forts Hughes and Drum, churned the channel between Bataan and Corregidor into a surging froth, whipped by shell fragments and explosions. The moon's steady light revealed many direct hits on barges and showed heavily burdened enemy soldiers struggling in the water and sinking under the weight of their packs and equipment. Still, some men reached shore and Colonel Sato was able to organize a drive toward his objective, Malinta Hill.

Individual enemy soldiers and machine-gun crews infiltrated across Kindley Field and through the rubble of torn barbed wire, blasted trees, and crater-pocked ground to Denver Battery, a sandbagged antiaircraft gun position which stood on relatively high ground south of Cavalry Point. The American gunners, whose weapons were out of action as a result of the bombardment, were unable to beat back the encroaching Japanese who established themselves in a commanding position with fields of fire over the whole approach route to the landing beaches. Captain Pickup's first word that the Japanese had seized Denver Battery came when he sent one of Company D's weapons platoon leaders, Marine Gunner Harold M. Ferrell, to establish contact with the battery's defenders. Ferrell and one of his men found the battery alive with enemy soldiers digging in and setting up automatic weapons. Ferrell immediately went back to his defense area west of Infantry Point and brought up some men to establish a line "along the hogsback to prevent the enemy from coming down on the back of the men on the beach."

Pickup came up shortly after Gunner Ferrell got his men into position and considered pulling Lieutenant Harris' platoon out of its beach defenses to launch an attack against the enemy. After a conference with Harris the company commander decided to leave the 1st Platoon in position. Japanese landing craft were still coming in, and the platoon's withdrawal would leave several hundred yards of beach open. The fact that enemy troops were ashore had been communicated to Lieutenant Colonel Beecher's CP just inside Malinta Tunnel's east entrance, and small groups of men, a squad or so at a time, were coming up to build on the line in front of Denver Battery. The enemy now fired his machine guns steadily, and intermittent but heavy shellfire struck all along the roads from Malinta to Denver. Casualties were severe throughout the area.

By 0130 surviving elements of 1/4 on the eastern tip of the island were cut off completely from the rest of the battalion. Beecher was forced to leave men in position on both shores west of Denver Battery to prevent the enemy landing behind his lines. All the men who could be spared from the beaches were being sent up to the defensive position astride the ridgeline just west of Denver, but the strength that could be assembled there amounted to little more than two platoons including a few Philippine Scouts from the silenced antiboat guns in 1/4's sector. No exact figures reveal how many Japanese were ashore at this time or how many casualties the 61st Infantry's assault companies had suffered, but it was plain that the enemy at Denver Battery outnumbered the small force trying to contain them, and Japanese snipers and infiltrating groups soon began to crop up in the rear of Pickup's position.

The situation clearly called for the commitment of additional men in the East Sector. Colonel Howard had made provision for this soon after getting word of the landing attempt. He alerted Schaeffer's command of two companies first, but held off committing Williams' battalion until the situation clarified itself. There was no guarantee that the Japanese would accommodate the 4th Marines by landing all their troops in the East Sector; in fact, there was a general belief among the men manning the defenses which commanded the ravines leading to Topside that the East Sector landing was not the main effort and that the enemy would be coming in against West and Middle Sector beaches. Complicating the entire problem of command in the confused situation was the fact that only runners could get word of battle progress to Beecher's and Howard's CP. And any runner, or for that matter any man, who tried to make the 1,000-yard journey from the Denver line to the mouth of Malinta Tunnel stood a good chance of never completing his mission. The area east of Malinta Hill was a killing ground as Schaeffer's men soon found out when they made their bid to reach Denver Battery.

The 4th Battalion in Action

Major Williams' 4th Battalion had been alerted early in the night's action, and he had ordered the issue of extra ammunition and grenades. At about 0100 he got the word to move the battalion into Malinta Tunnel and stand by. The sailors proceeded cautiously down the south shore road, waited for an enemy barrage which was hitting in the dock area to lift, and then dashed across to the tunnel entrance. In the sweltering corridor the men pressed back against the walls as hundreds of casualties, walking wounded and litter cases, streamed in from the East Sector fighting. The hospital laterals were filled to overflowing, and the doctors, nurses, and corpsmen tended to the stricken men wherever they could find room to lay a man down. At 0430, Colonel Howard ordered Williams to take his battalion out of the tunnel and attack the Japanese at Denver Battery.

The companies moved out in column. About 500 yards out from Malinta they were caught in a heavy shelling that sharply reduced their strength and temporarily scattered the men. The survivors reassembled and moved toward the fighting in line of skirmishers. Companies Q and R, commanded by two Army officers, Captains Paul C. Moore and Harold E. Dalness, respectively, moved in on the left to reinforce the scattered groups of riflemen from Companies A and P who were trying to contain the Japanese in the broken ground north of Denver Battery. The battery position itself was assigned to Company T (Lieutenant Bethel B. Otter, USN), and two platoons of Company S, originally designated the battalion reserve, were brought up on the extreme right where Lieutenant Edward N. Little, USN, was to try to silence the enemy machine guns near the water tower. The bluejackets filled in the gaps along the line--wide gaps, for there was little that could be called a firm defensive line left--and joined the fire fight.

The lack of adequate communications prevented Colonel Howard from exercising active tactical direction of the battle in the East Sector. The unit commanders on the ground, first Captain Pickup, then Major Schaeffer, and finally Major Williams made the minute-to-minute decisions that close combat demanded. By the time Williams' battalion had reorganized and moved up into the Marine forward positions, Schaeffer's command was practically nonexistent. Williams, by mutual consent (Schaeffer was senior), took over command of the fighting since he was in a far better position to get the best effort out of his bluejackets when they attacked.

At dawn Major Williams moved along the front, telling his officers to be ready to jump off at 0615. The company and platoon command posts were right up on the firing line and there were no reserves left; every officer and man still able to stand took part in the attack. On the left the Japanese were driven back 200-300 yards before Williams sent a runner to check the advance of Moore and Dalness; the right of the line had been unable to make more than a few yards before the withering fire of the Denver and water tower defenses drove the men to the deck. The left companies shifted toward Denver to close the gap that had opened while the men on the right tried to knock out the Japanese machine guns and mortars. Lieutenant Otter was killed while leading an attack, and his executive, Captain Calvin E. Chunn, took over; Chunn was wounded soon after as Company T charged a Japanese unit which was setting up a field piece near the water tower. Lieutenant Little was hit in the chest and Williams sent a Philippine Scout officer, First Lieutenant Otis E. Saalman, to take over Company S.

The Marine mortars of 1/4, 3-inch Stokes without sights, were not accurate enough to support Williams' attack. He had to order them to cease fire when stray rounds fell among his own men, who had closed to within grenade range of the Japanese. Robbed of the last supporting weapons that might have opened a breach in the Denver position, the attack stalled completely. Major Schaeffer sent Warrant Officer Ferguson, who had succeeded to command of Company O when Captain Chambers was wounded, to Colonel Howard's CP to report the situation and request reinforcements. Ferguson, like Schaeffer and many of the survivors of 1/4 and the reserve, was a walking wounded case himself. By the time Ferguson got back through the enemy shelling to Malinta at 0900, Williams had received what few reinforcements Howard could muster. Captain Herman H. Hauck and 60 men of the 59th Coast Artillery, assigned by General Moore to the 4th Marines, had come up and Williams sent them to the left flank to block Japanese snipers and machine-gun crews infiltrating along the beaches into the rear areas.

At about 0930 men on the north flank of the Marine line saw a couple of Japanese tanks coming off barges near Cavalry point, a move that spelled the end on Corregidor. The tanks were in position to advance within a half hour, and, just as the men in front of Denver Battery spotted them, enemy flares went up again and artillery salvoes crashed down just forward of the Japanese position. Some men began to fall back, and though Williams and the surviving leaders tried to halt the withdrawal, the shellfire prevented them from regaining control. At 1030 Williams sent a message to the units on the left flank to fall back to the ruins of a concrete trench which stood just forward of the entrance to Malinta Tunnel. The next thirty minutes witnessed a scene of utter confusion as the Japanese opened up on the retreating men with rifles, mortars, machine guns, and mountain howitzers. Flares signalled the artillery on Bataan to increase its fire, and a rolling barrage sung back and forth between Malinta and Denver, demolishing any semblance of order in the ranks of the men straining to reach the dubious shelter of the trench. "Dirt, rocks, trees, bodies, and debris literally filled the air,"[42] and pitifully few men made it back to Malinta.

Williams, who was wounded, and roughly 150 officers and men, many of them also casualties, gathered in the trench ruins to make a stand. The Japanese were less than three hundred yards from their position and enemy tanks could be seen moving up to outflank their line on the right. The Marine major, who had been a tower of strength throughout the hopeless fight. went into the tunnel at 1130 to ask Howard for antitank guns and more men. But the battle was over: General Wainwright had made the decision to surrender.

Silver Star

From Hall of Valor:

The President of the United States of America takes pride in presenting the Silver Star (Posthumously) to Major Francis Hubert Williams (MCSN: 0-4533), United States Marine Corps, for conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity as a member of the Beach Defenses in action against enemy Japanese forces on Corregidor, Philippine Islands on 2 May 1942. When direct hostile artillery hits on our powder magazines caused disastrous explosions and set fire to several ammunition dumps nearby, Major Williams unhesitatingly made his way through the flaming debris and flying shell fragments to take charge of a group of volunteers attempting to evacuate the wounded and to extinguish the inferno. Calmly directing his valiant men under the most chaotic conditions he succeeded in controlling the fire and in removing many wounded and trapped men to safety. By his resolute courage and unswerving devotion to duty, Major Williams was instrumental in saving numerous lives, thereby reflecting great credit upon himself and the United States Naval Service.

General Orders: War Department, General Orders No. 60 (June 26, 1946)

Service: Marine Corps

Rank: Major

From Hall of Valor:

The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress July 9, 1918, takes pride in presenting a Bronze Oak Leaf Cluster in lieu of a Second Award of the Silver Star (Army Award) (Posthumously) to Major Francis Hubert Williams (MCSN: 0-4533), United States Marine Corps, for conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in action against the enemy while serving as Commanding Officer, Fourth Tactical Battalion, Fourth Marine Regiment, in action at Corregidor during the defense of the Philippine Islands, on 2 May 1942. Learning that a battery had been practically destroyed and set afire by a heavy enemy artillery concentration, Major Williams organized a rescue squad and, despite the imminence of an explosion from the magazine, courageously directed the removal of the wounded and extinguishment of the flames. Major Williams' conduct reflects credit upon himself and the United States Marine Corps.

General Orders: War Department, General Orders No. 60 (June 26, 1946)

Service: Marine Corps

Rank: Major

Prisoner of War Medal

From Hall of Valor:

Lieutenant Colonel Francis Hubert Williams (MCSN: 0-4533), United States Marine Corps, was captured by the Japanese after the fall of Corregidor, Philippine Islands, on 6 May 1942, and was held as a Prisoner of War until his death while still in captivity.

General Orders: NARA Database: Records of World War II Prisoners of War, created, 1942 - 1947

Service: Marine Corps

Rank: Lieutenant Colonel

The "Register of Commissioned and Warrant Officers of the United States Navy and Marine Corps" was published annually from 1815 through at least the 1970s; it provided rank, command or station, and occasionally billet until the beginning of World War II when command/station was no longer included. Scanned copies were reviewed and data entered from the mid-1840s through 1922, when more-frequent Navy Directories were available.

The Navy Directory was a publication that provided information on the command, billet, and rank of every active and retired naval officer. Single editions have been found online from January 1915 and March 1918, and then from three to six editions per year from 1923 through 1940; the final edition is from April 1941.

The entries in both series of documents are sometimes cryptic and confusing. They are often inconsistent, even within an edition, with the name of commands; this is especially true for aviation squadrons in the 1920s and early 1930s.

Alumni listed at the same command may or may not have had significant interactions; they could have shared a stateroom or workspace, stood many hours of watch together, or, especially at the larger commands, they might not have known each other at all. The information provides the opportunity to draw connections that are otherwise invisible, though, and gives a fuller view of the professional experiences of these alumni in Memorial Hall.

October 1930

January 1931

April 1931

July 1931

October 1931

January 1932

April 1932

October 1932

January 1933

April 1933

July 1933

October 1933

April 1934

July 1934

October 1934

January 1935

April 1935

October 1935

January 1936

April 1936

July 1936

January 1937

April 1937

September 1937

January 1938

October 1939

June 1940

November 1940

April 1941

The "category" links below lead to lists of related Honorees; use them to explore further the service and sacrifice of alumni in Memorial Hall.