WILLIAM J. TATE, JR., LT, USN

William Tate, Jr. '38

Lucky Bag

From the 1938 Lucky Bag:

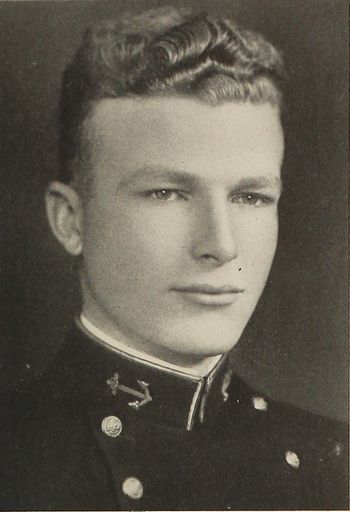

WILLIAM JAMES TATE, JR.

Baltimore, Maryland

Jim, Bill

A superlative member of the class of 1938, Jimmy Tate, curly-haired and smiling, is one of our youngest classmates. Sometimes known as Bill and other times as Jim or Jimmy, he's always the same smiling sincere character. With eagerness and determination, Jimmy came directly to the Naval Academy from Forest Park High School in Baltimore. We are aware of Jim's sterling inheritance as a supple-bodied athlete, with Irish determination, and natural nautical interests. Perhaps his knowledge and ability in boat handling drew his interest to the Severn and to the long oars of crew. Too light to wield an oar with the Academy's six-footers, he was chosen as manager of crew early in his second class year. Although too light to participate in the major sports, he is their greatest supporter. Here is the portrayal of will and determination.

Crew Manager 2, 1; Boat Club; Lieutenant (j.g.).

WILLIAM JAMES TATE, JR.

Baltimore, Maryland

Jim, Bill

A superlative member of the class of 1938, Jimmy Tate, curly-haired and smiling, is one of our youngest classmates. Sometimes known as Bill and other times as Jim or Jimmy, he's always the same smiling sincere character. With eagerness and determination, Jimmy came directly to the Naval Academy from Forest Park High School in Baltimore. We are aware of Jim's sterling inheritance as a supple-bodied athlete, with Irish determination, and natural nautical interests. Perhaps his knowledge and ability in boat handling drew his interest to the Severn and to the long oars of crew. Too light to wield an oar with the Academy's six-footers, he was chosen as manager of crew early in his second class year. Although too light to participate in the major sports, he is their greatest supporter. Here is the portrayal of will and determination.

Crew Manager 2, 1; Boat Club; Lieutenant (j.g.).

Loss

William was lost when his aircraft crashed into the Chesapeake Bay while testing large caliber bombs from a fighter on the afternoon of April 13, 1944.

The accident report provided by his great nephew states he was engaged on an "experimental flight" "to test max safe angle of dive for VF [fighters] without bomb displacement gear. During dive an object (believed prop) was seen to fly off. Plane rolled and crashed. Pilot jumped but could not be found (possibly hit by plane while jumping). Possibly bomb bib or maybe entire bomb rack failed and hit prop."

Other Information

From researcher Kathy Franz:

William graduated from Forest Park High School in 1933. Track; Jubilee; Orchestra; Variety Soccer; Interclass Sports; Christmas Play; Ice Hockey. Jimmy has led us to believe that music will be his life work. His fine scholastic average and his music should bring him success.

He also attended Cochran & Bryan Preparatory School, and he entered the Naval Academy based on competitive examination.

William finished advanced training at the Naval Air School in Pensacola in March 1941 and was assigned to the cruiser scouting squadron of the U. S. S. Salt Lake City.

William and Helene White were married in the chapel of the Naval Academy on April 16, 1941. She was also a graduate of Forest Park High School in 1934.

His father was a construction engineer and one-time president of the local Democratic Club; he was also a Navy Lt Commander in WWI. His mother was Mary.

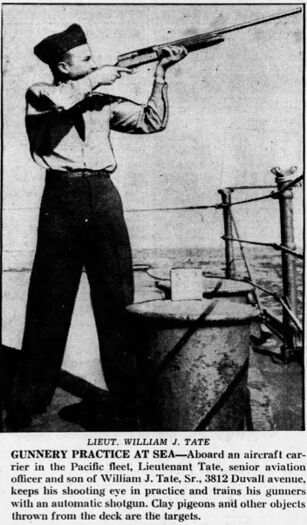

From The Evening Sun, Baltimore, Maryland, September 28, 1942.

Tell the Folks to Send More Planes, Pilot Writes

Lieut. William J. Tate Tells How Carrier Gunners Bang Away at Clay Pigeons During Short Intervals of Rest

When not in the air busy looking for enemy planes, aviation gunners aboard one United States carrier in the Pacific keep their shooting eye in trim by banging away at clay pigeons, Lieut. William J. Tate writes in a letter to his parents here.

Lieutenant Tate, a senior aviation officer aboard an aircraft carrier, explained that he bought a shotgun to teach his gunners how to hit a moving target. Whenever he and his gunners have free time now, they spend it by shooting at clay pigeons or other targets thrown over the side of the ship.

Want More Planes, Bombs

Declaring that he believes many people are worrying too much about the home front, Lieutenant Tate wrote:“Too many worry too little about producing planes and bombs that we can get out and win the war with.

“We don’t want more pay; we want more planes. I never get a chance to spend my money anyway.”

Forest Park Graduate

A native of Boston who moved here with his family at the age of four, Lieutenant Tate, now 26, was graduated from Forest Park High school in 1933, and after a year at the Annapolis Preparatory school entered the United States Naval Academy, from which he was graduated in 1938.Sent immediately to the Pacific fleet, Tate spent a year on a battleship, then was transferred to the Cassin, destroyer subsequently sunk at Pearl Harbor. His next transfer was to Pensacola, Fla., where he received his pilot’s license after eight months. He was returned to active duty on the carrier immediately after his marriage at the Naval Academy to Miss Helene White, Baltimore teacher.

From Service Family

He is a member of a family which might claim a record for war participation. His father, William J. Tate, Sr., of 3812 Duvall avenue, is a retired lieutenant commander in the navy; his mother was a British Red Cross worker during the World War, a brother Ensign Norman L. Tate [‘42,] 24, served on a carrier during the Coral Sea and Midway battles.A sister, Mary, 20, is secretary to the commander of Kaneohe Naval Air Base in Hawaii; and another brother, Robert, 18, is now at the Annapolis Preparatory School. A 13-year-old brother [Donald] also plans to enter the navy.

William has a memory marker in Maryland.

Remembrance

From William's great nephew on August 5, 2023:

Growing up I heard nothing but great stories about him- how generous and outgoing he was, brave, persistent and ebullient. According to Bob (my grandfather) he was the ideal older brother and set an example that Bob would carry through his life and into business success.

Career

From naval aviation historian Richard Leonard via email on February 9, 2018:

- NAS Pensacola attached for HTA flight training, 8/12/1940

- NAS Pensacola designated NA # 7235, 3/3/1941

- Date of rank LTJG from 1 Jul 1941 USN Register, 6/2/1941

- Date of rank LT from 1 Jul 1942 USN Register, 6/15/1942

- VCS-5 USS Salt Lake City (CA-25), 10/11/1942

- NATC ArmTestDiv NAS Patuxent River DFC KIFA, 4/13/1944

William reported to USS Salt Lake City (CA 25) as a scout pilot in May 1941.

He was promoted to Lieutenant on June 18, 1942.

From Salt Lake City memorial site:

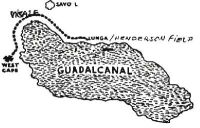

At 2200 on Oct. 11 1942 W. J. Tate Jr., Lieut. and Claude W. Morgan, ARM1c were catapulted from the USS Salt Lake City about nine miles off West Cape, Guadalcanal. It was a dark night and the ground crew had loaded extra flares in the rear cockpit lengthwise instead of athwartship as instructed.

The acceleration experienced when the aircraft was catapulted caused the flares to fall out of their storage, setting the tail of the plane on fire. It never got above 200 feet, and within seconds the fire was spreading through out the entire aircraft. Morgan had to immediately crawl out of the rear seat onto the wing and Tate couldn't see the water, horizon or even the instrument panel, He gunned the engine two or three times trying to blow the fire out and eased down toward the water trying to land in a cross wind.

The airplane hit the water right wing down and didn't bounce, throwing Morgan clear, however he received a bad cut over one eye and a wrenched shoulder. The plane was still on fire and Tate was out on the wing before his head began to clear, he did not remember unbuckling his safety belt or climbing out of the cockpit. He suddenly became afraid that the gas tanks might explode, so he swam over to join Morgan and together they swam about 200 feet clear of the aircraft. They tried to signal the ship with a pencil light but didn't have any luck.

The fire burned for about seven more minutes before the plane turned over and put it out. They swam back to the plane, Morgan held onto the tail trying to relax the pain in his wrenched shoulder while Tate extracted the life raft, it took about 10 or more dives down to the compartment it was stowed. The life raft had survived the fire and inflated properly, which was a good thing as Tate had torn up his life jacket so badly extracting the raft, he had to throw it away. He also got gasoline, that was floating on the surface of the water, in his eyes and swallowed some which immediately made him sick.

They climbed into the raft and started paddling away from the plane toward the west end of Guadalcanal, as enemy troops were all along the shore where they now were and it would be impossible to land and walk to Lunga. About 2330 they witnessed the battle of Cape Esperance. It appeared to them as though three groups of ships, with our ships in the middle and shooting in both directions.

It got very cold that night, even though they were fully clothed, except Tate had discarded his helmet and gloves which later proved to be a mistake, at daylight they were about five miles off West Cape. For provisions they had five bottles of Horlick's malted milk tablets and two gallons of water. Morgan had bought the canteen at a hardware store and Tate the malted milk tablets in Honolulu with their own money. This was all they would eat, except for floating coconuts they managed to fish out of the water, the next three days.

The first day they continued paddling, keeping about six miles off shore hoping to be spotted by some of our planes looking for survivors, but no such luck, even though six planes flew directly four hundred feet overhead on a strafing run toward Japanese targets. To the north a destroyer and some planes could be seen picking up survivors from the destroyer SS Duncan, which was our only ship sank in the battle of Cape Esperance.

Life in the raft was always wet as waves would slop in and they could never get completely dry. It was cold at night and hot during the day. Tate had to remove his underwear, tear it up and cover his head, face and hands to protect them from the sun and help warm them at night. His hands and face was tender from the gasoline burns received while diving to get the raft out of the airplane, he now wished he hadn't discarded his helmet and gloves. Morgan's wrenched shoulder and cut above his eye seemed to get better with time.

The second day they found a dugout canoe with a hole in it, patched it up and tried paddling it towing the raft. It went faster but was so delicately balanced and difficult they went back to the raft. By afternoon they managed to get around the west tip of the island and a fresh wind came up which eased the burden of paddling but blew them within a half mile of the shore. A Japanese sniper opened up on them and they promptly went overboard. He fired about 10 rounds but the closest landed about six feet away. The swimming cooled them off and they felt much better. As they paddled away they noticed a number of power boats and barges badly damaged on the beach. That evening another rubber boat could be seen coming from Savo island which started chasing them, it was some Japs bringing back fruit and vegetables so they easily out distanced them. Tate and Morgan had only a sheaf knife and five pen knives, they wouldn't have been much of a match for anyone with a gun. The Japs didn't fire at them but one from Visale, on Guadalcanal, tried his luck but didn't come very close.

Early on the third night ships started firing at Lunga and received answering fire from shore. Later three Destroyers passed just east of Savo island and a few minutes later a Japanese destroyer came around the west side headed straight toward the two men in the raft. They held their breath and just before it got to them the destroyer veered off but still passed so close, Morgan and Tate could hear them talking. It was doing ten or twelve knots and came close enough to nearly swamp their raft even though it was a calm sea that night.

Shortly after a large campfire and light appeared on the beach, obviously to give navigational aid to the Japanese, as ships started bombarding Lunga beach. They received return fire than swung toward Tulagi and fired briefly and retired to the north. They were accompanied by a Japanese battleship and as soon as they retired the large campfire and light on the beach went out.

On the last day both men felt quite sick from the sun but kept paddling toward Lunga, their progress became difficult as a southwest wind necessitated that one to bail out water as the other paddled. All day the two men in the raft watched our planes bomb Japanese positions but finally turned toward shore, and right in the nick of time! A Higgins boat spotted them and picked them up. For the two men in the raft the Battle of Cape Esperance lasted sixty seven hours and covered fifty miles.

Photographs

Distinguished Flying Cross

From Hall of Valor:

The President of the United States of America takes pride in presenting the Distinguished Flying Cross (Posthumously) to Lieutenant William J. Tate, Jr., United States Navy, for extraordinary achievement while participating in aerial flight as Test Pilot and Gunnery Officer attached to the Armament Test Department at Naval Air Station, Patuxent River, Maryland. Lieutenant Tate carried out extremely dangerous work of testing mines and bombs. Throughout his intelligent analysis of test data, he made important contributions to the effectiveness of naval aviation and the future safety of naval aviators. He was killed on 13 April 1944 while making tests to determine safe angles of dive for fighter planes carrying large caliber bombs.

General Orders: Bureau of Naval Personnel Information Bulletin No. 329 (August 1944)

Action Date: World War II

Service: Navy

Rank: Lieutenant

The "Register of Commissioned and Warrant Officers of the United States Navy and Marine Corps" was published annually from 1815 through at least the 1970s; it provided rank, command or station, and occasionally billet until the beginning of World War II when command/station was no longer included. Scanned copies were reviewed and data entered from the mid-1840s through 1922, when more-frequent Navy Directories were available.

The Navy Directory was a publication that provided information on the command, billet, and rank of every active and retired naval officer. Single editions have been found online from January 1915 and March 1918, and then from three to six editions per year from 1923 through 1940; the final edition is from April 1941.

The entries in both series of documents are sometimes cryptic and confusing. They are often inconsistent, even within an edition, with the name of commands; this is especially true for aviation squadrons in the 1920s and early 1930s.

Alumni listed at the same command may or may not have had significant interactions; they could have shared a stateroom or workspace, stood many hours of watch together, or, especially at the larger commands, they might not have known each other at all. The information provides the opportunity to draw connections that are otherwise invisible, though, and gives a fuller view of the professional experiences of these alumni in Memorial Hall.

July 1938

January 1939

October 1939

June 1940

November 1940

CDR William Sample '19

LT William Pennewill '29

LT Finley Hall '29

LT John Yoho '29

LT Lance Massey '30

LT George Bellinger '32

LT Martin Koivisto '32

LT John Spiers '32

LT Daniel Gothie '32

LT Dewitt Shumway '32

LT Albert Major, Jr. '32

LTjg John Phillips, Jr. '33

ENS Frank Peterson '33

LTjg Charles Brewer '34

LTjg Walker Ethridge '34

CAPT Floyd Parks '34

LTjg Charles Ware '34

LTjg Frank Whitaker '34

LTjg Philip Torrey, Jr. '34

LTjg George Nicol '34

LTjg Victor Gadrow '35

LTjg Richard Stephenson '35

LTjg Allan Edmands '35

LTjg Roy Krogh '36

LTjg Porter Maxwell '36

LTjg Richard Hughes '37

LTjg Frank Henderson, Jr. '37

LTjg John Thomas '37

LTjg John Boal '37

ENS Harry Howell '38

ENS Eric Allen, Jr. '38

ENS James Ginn '38

ENS Oswald Zink '38

ENS Frank Case, Jr. '38

ENS Howard Fischer '38

ENS Edmundo Gandia '38

ENS Charles Reimann '38

ENS Howard Clark '38

ENS Roy Hale, Jr. '38

ENS Leonard Thornhill '38

ENS Osborne Wiseman '38

ENS Curtis Howard '38

ENS Jep Jonson '38

ENS Roy Green, Jr. '38

ENS Marion Dufilho '38

2LT James Owens '38

ENS William Brady '38

ENS Charles Anderson '38

ENS Carl Holmstrom '38

ENS Charles King '38

2LT John Maclaughlin, Jr. '38

2LT Douglas Keeler '38

ENS Harry Bass '38

ENS John Kelley '38

ENS John Erickson '38

ENS William Lamberson '38

ENS Donald Smith '38

ENS Frank Quady '38

ENS Richard Crommelin '38

ENS Robert Seibels, Jr. '38

ENS Alphonse Minvielle '38

April 1941

Memorial

Tate Road aboard Naval Air Station Patuxent River is named for William.

The "category" links below lead to lists of related Honorees; use them to explore further the service and sacrifice of alumni in Memorial Hall.